Summary Card

Definition of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Malignant tumour from epidermal keratinocytes or hair follicles.

Diagnosis of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Indurated nodular keratinizing or crusted tumour that may ulcerate. It may also present as an ulcer without keratinization.

Risk Factors for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Sun exposure, pale skin, and medical conditions causing immunosuppression or immunocompromised.

Surgical Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

First-line standard of care. A biopsy can be considered if clinical uncertainty and margins depend on the risk group.

Radiotherapy for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Primarily an adjuvant treatment for specific high-risk tumours. It can be considered the first line if surgery is not feasible.

Medical Treatments for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Medical treatment for Squamous Cell Carcinoma include immune checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, EGFR inhibitors, and electrochemotherapy.

Risk Groups for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

It is a spectrum from low to very high risk based on TNM staging, patient status, and margin criteria.

TNM Staging for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

TNM (Tumour, Node and Metastasis) is used to classify and stage patients.

Follow-Up for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

All patients have post-operative visits to confirm the diagnosis and education. Long-term follow-up is based on tumour & patient risk status.

Definition of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

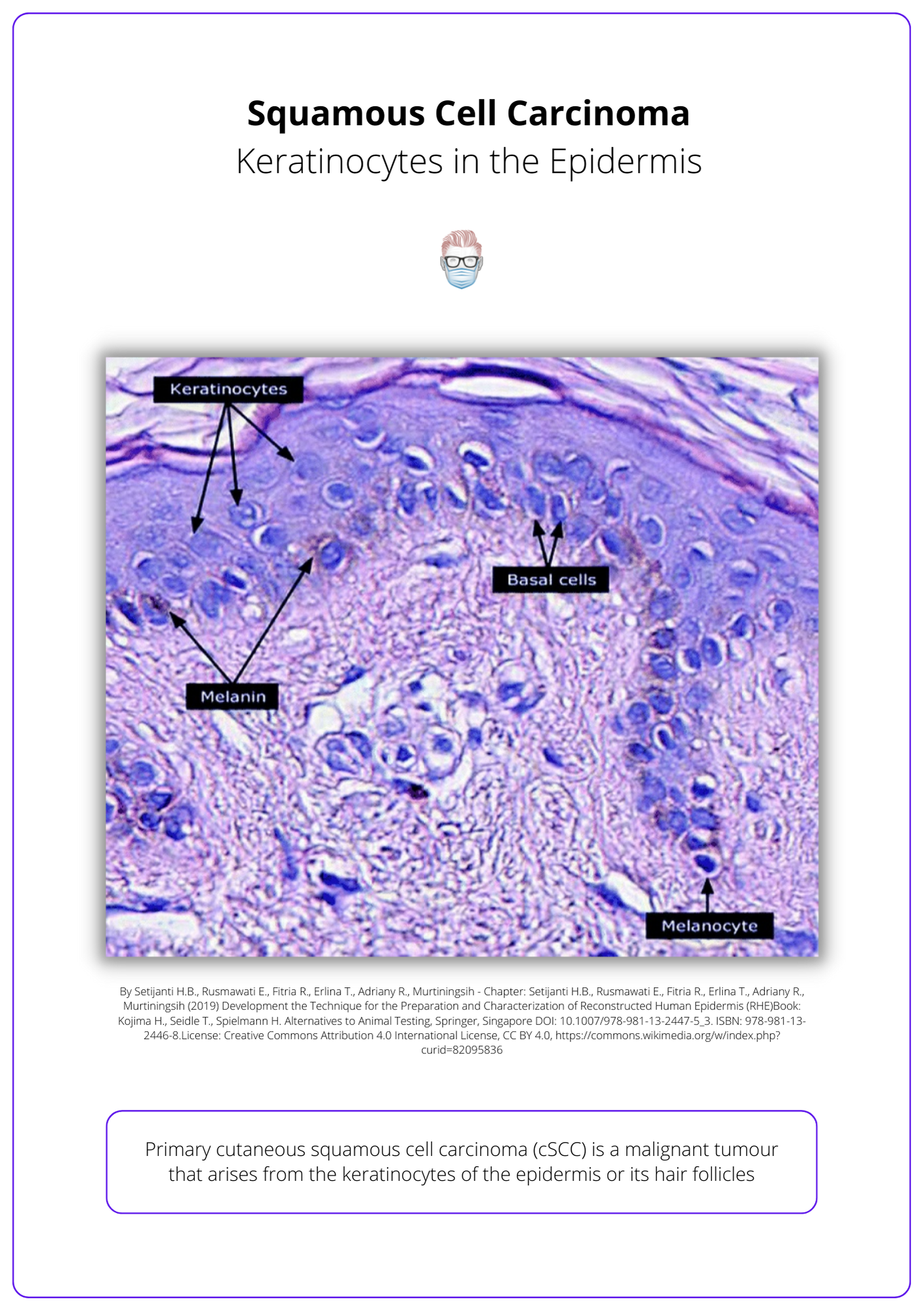

Primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant tumour that arises from the keratinocytes of the epidermis or its hair follicles. Aggressive histologic subtypes include adenoid (acantholytic), adenosquamous, desmoplastic or metaplastic.

Definition of Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Diagnosis of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is a clinical diagnosis confirmed by histology. Patients may require radiological investigations to staging or depth of invasion into bone.

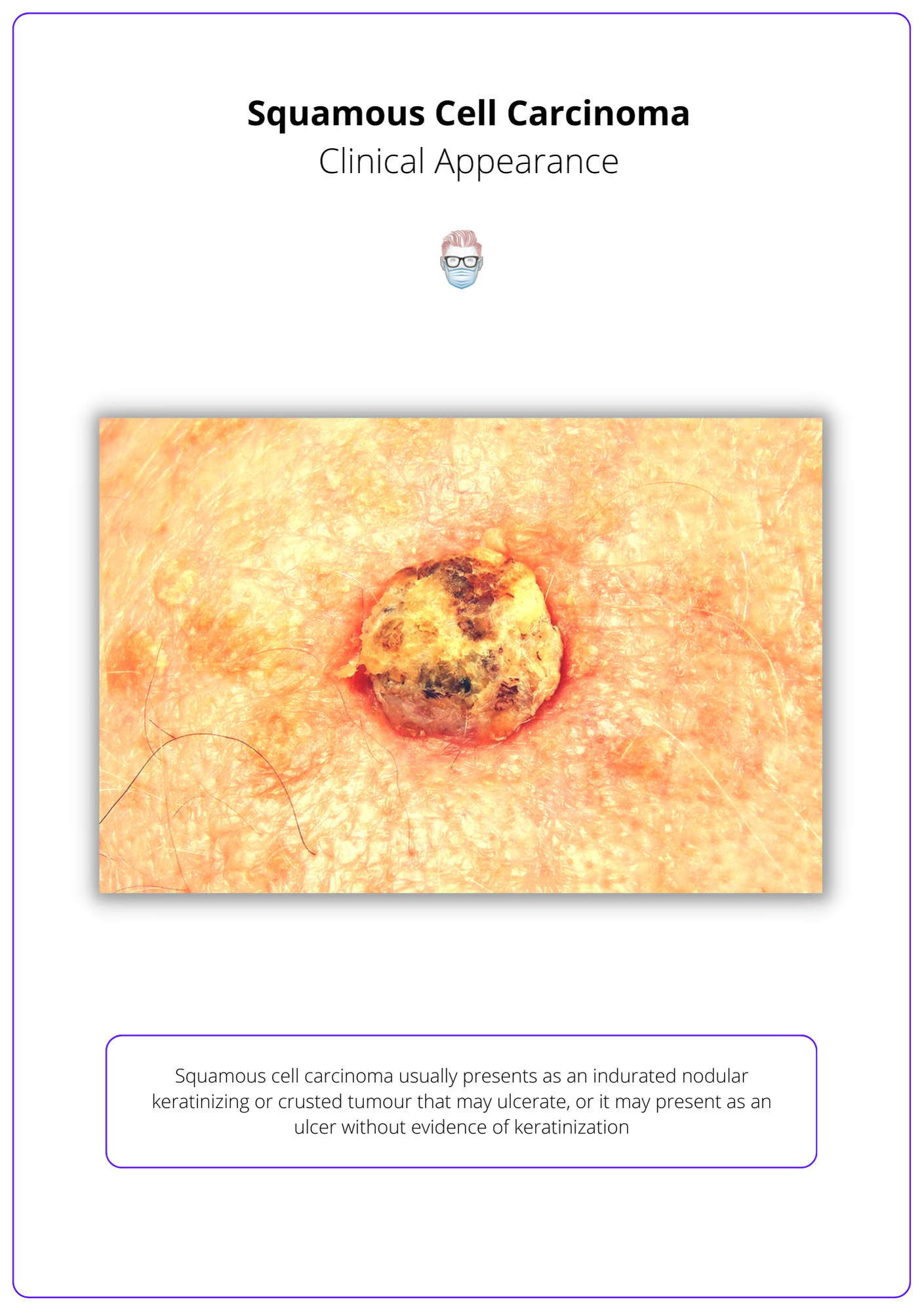

Clinical Diagnosis

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is generally a clinical diagnosis based on a history of rapid growth and specific features on examination.

Squamous cell carcinomas are indurated, nodular, keratinizing, or crusted tumours that may ulcerate (Keohane et al., 2021).

Histological Diagnosis

If there is clinical uncertainty, a biopsy can be performed. Biopsy should include deep reticular dermis because infiltration may only be present at deeper margins. The histological appearance is:

- Dysplastic epidermal keratinocytes invading the basement membrane into the dermis

- Keratin pearls

- The degree of keratinisation can be variable

Radiology

Radiological workup for SCC is not indicated for all patients. It can be used for staging, depth of invasion, or perineural invasion.

The current recommendations for radiology (Keohane et al., 2021):

- Staging if clinically concerned for local, regional or distant spread. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy of suspicious nodes. Contrast-enhanced CT scan or PET/CT should be considered to assess the extent of regional disease and for distant metastases. (Lansbury et al., 2013)

- Depth of invasion into underlying structures. If perineural or deep soft tissue, consider MRI. If there is bone involvement, CT with contrast is preferred if there are no contraindications20–22. (Rowe et al., 1992 & Chren et al., 2013)

Risk Factors for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The main risk factors for developing squamous cell carcinoma are sun exposure, pale skin, and medical conditions resulting in immunosuppression or immunocompromise.

Sun Exposure

The risk of SCC increases with age from natural cumulative sun exposure. There is a strong correlation with the following (Juzeniene et al., 2014 & Box et al., 2001):

- Chronic sun exposure

- Total site-specific exposure

- Number of site-specific sunburns

Fitzpatrick Type I + II

- Individuals with fair skin, hair, and eye colour.

- Susceptibility to oncogenic UV damage in genes linked with pigmentation. (Box et al., 2001)

Co-Morbidities

- Skin Cancers: up to 50% of skin cancer in 5 years (Wu et al., 2014).

- Chronic ulcers: Marjolin’s Ulcer8 or Burn Scars (Das et al., 2015).

- Organ transplantation/immunosuppression (Kim et al., 2016).

- Pre-existing lesions: Actinic Keratosis11 or Bowen’s Disease (Glogau, 2000 & Eimpunth et al., 2017).

- Genetic syndromes: Albinism14 or Xeroderma Pigmentosum (Bradford et al., 2011).

- Haematological conditions: Lymphoma or Leukemia.

Less Common

- Exposure to chemicals: pesticides, herbicides or arsenic.

- Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB).

Surgical Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Surgical resection is the standard of care. A biopsy can be considered if clinical uncertainty and margins depend on the risk group.

Standard Surgical Excision

This is the first-line treatment option for resectable primary cutaneous SCC.

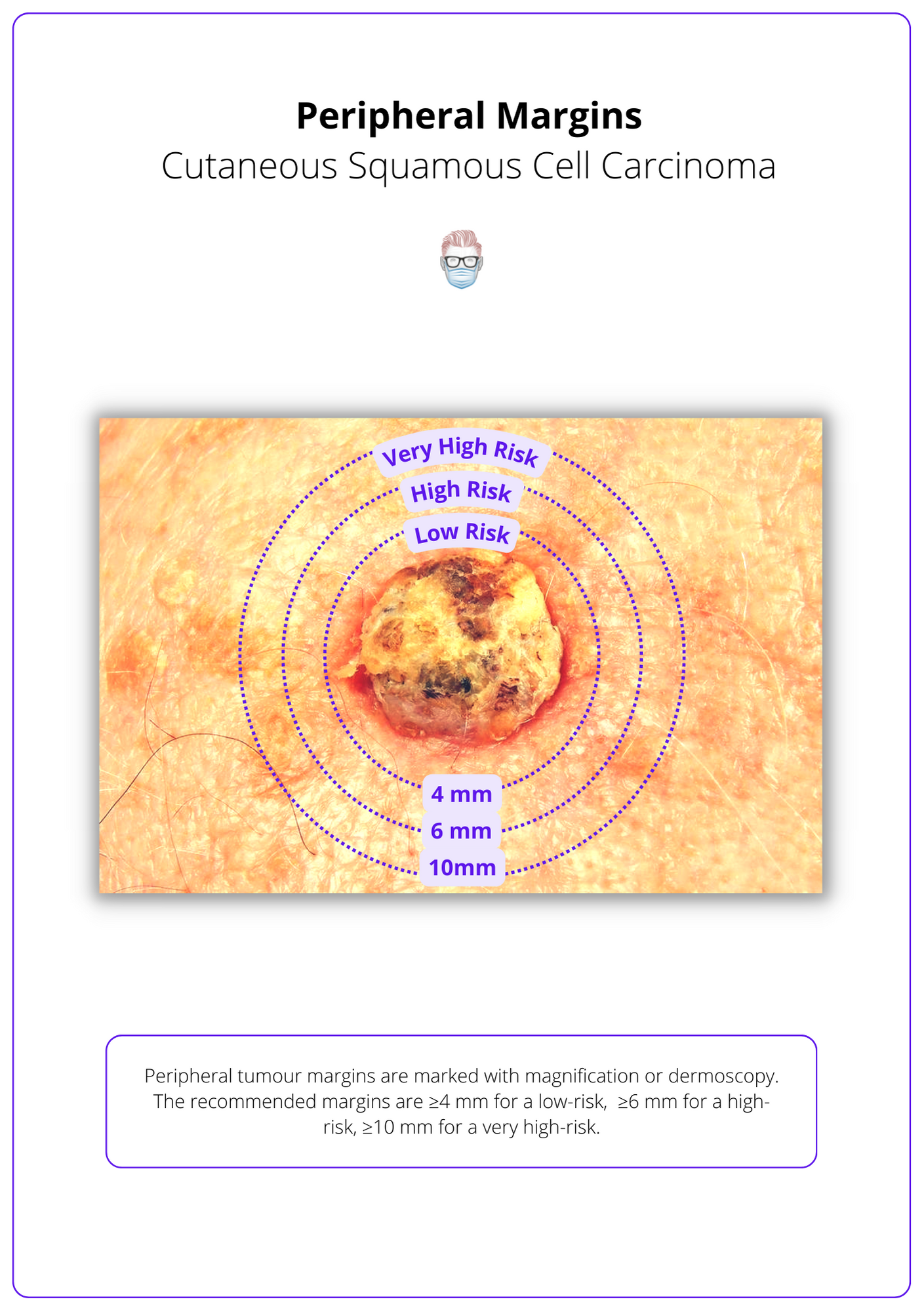

The following peripheral margins are recommended (Keohane et al., 2021):

- ≥ 4 mm for a low-risk cSCC tumour.

- ≥ 6 mm for a high-risk cSCC tumour.

- ≥ 10 mm for a very high-risk cSCC tumour.

These surgical margins achieve a 5-year disease-free rate of >91%26 (Karagas et al., 1992).

The following deep margins are recommended (Keohane et al., 2021):

- Mobile lesions should be excised in the next clear surgical plane.

- Scalp lesions should be excised with the galea.

- Deeply infiltrating or fixed lesions excised with underlying structure (determined clinically, or by imaging, or both).

Other Surgical Options

- Moh’s Micrographic Surgery can be considered for high-risk lesions, poorly defined tumour margins, or in sites where tissue conservation is important for function. This has 96% cure rates of 96% for primary cSCCs and 77% for recurrent cSCCs. (Turner et al., 2000)

- Curettage and electrodesiccation can be considered for low-risk lesions and patients. Surgical resection is required if adipose is reached. Lower-quality data shows cure rates ~95% at 5 years (Chren et al., 2013 & Lansbury et al., 2013). This does not allow for margin assessment, but histology should be reviewed for any high-risk features.

Positive or Near-Margins in SCC

Additional treatment options should be offered if margins are positive after excision or narrowly excised in high-risk patients.

- Observation: low-risk tumour, low-risk patient & narrow margins (<1mm).

- Wider Excision, Mohs or Adjuvant Radiotherapy in high-risk patients with positive or close margins (<1 mm).

Lymph Nodes

The nodal status of patients with squamous cell carcinoma is guided by clinical examination.

The criteria for selecting patients and survival benefits for Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is unclear. The current recommendations for sentinel node biopsy to consider high-risk cases of primary cSCC in a clinical trial or after MDT discussion (Keohane et al., 2021).

Lymph node clearance is for patients suitable for surgery with clinical or radiological lymph node involvement.

Radiotherapy for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Radiotherapy is primarily used as an adjuvant treatment for specific high-risk tumors and patients. It can be considered first-line if surgery is not feasible.

Radiotherapy can be considered as primary treatment for non-surgical candidates or as adjuvant therapy for certain types of squamous cell carcinomas. This should be discussed as an MDT. This improves local control and disease-free survival, but there is likely no survival benefit30,31.

Primary Radiotherapy

Primary radiotherapy can be considered in the following patients:

- Surgery is not feasible, challenging or results in an unacceptable functional or aesthetic outcome.

- Patient preference.

Adjuvant Radiotherapy

Consider adjuvant radiotherapy after MDT discussion in patients with:

- Narrow excised tumour margins (<1mm).

- Completely excised T3 tumours.

- Incompletely excised if further surgery is not possible, high risk of local recurrence, perineural invasion (multifocal, named nerve, diameter >0.1mm, below dermis), recurrent disease, immunocompromised.

Radiotherapy should not be offered to completely excise T1 or T2 cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with microscopic, dermal-only, nerve diameter<0.1mm perineural invasion.

If the perineural invasion is present, conformal radiotherapy is an option for the entire course of the involved nerve when surgery is inappropriate. This can be considered in SCCs with perineural invasion and symptomatic perineural invasion and/or radiological evidence of perineural invasion

Medical Treatments for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Treatment options for metastatic or locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma include immune checkpoint inhibitors, systemic chemotherapy, EGFR inhibitors, and electrochemotherapy, depending on the patient's specific situation and the suitability of other therapies.

These options are generally considered for patients with metastatic SCC.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in people with locally advanced cSCC where curative surgery or radiotherapy is not reasonable.

- Systemic chemotherapy or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors in people with metastatic cSCC with contraindications to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

- Electrochemotherapy in people with locally advanced cSCC in palliative settings if other local or systemic therapies are not appropriate.

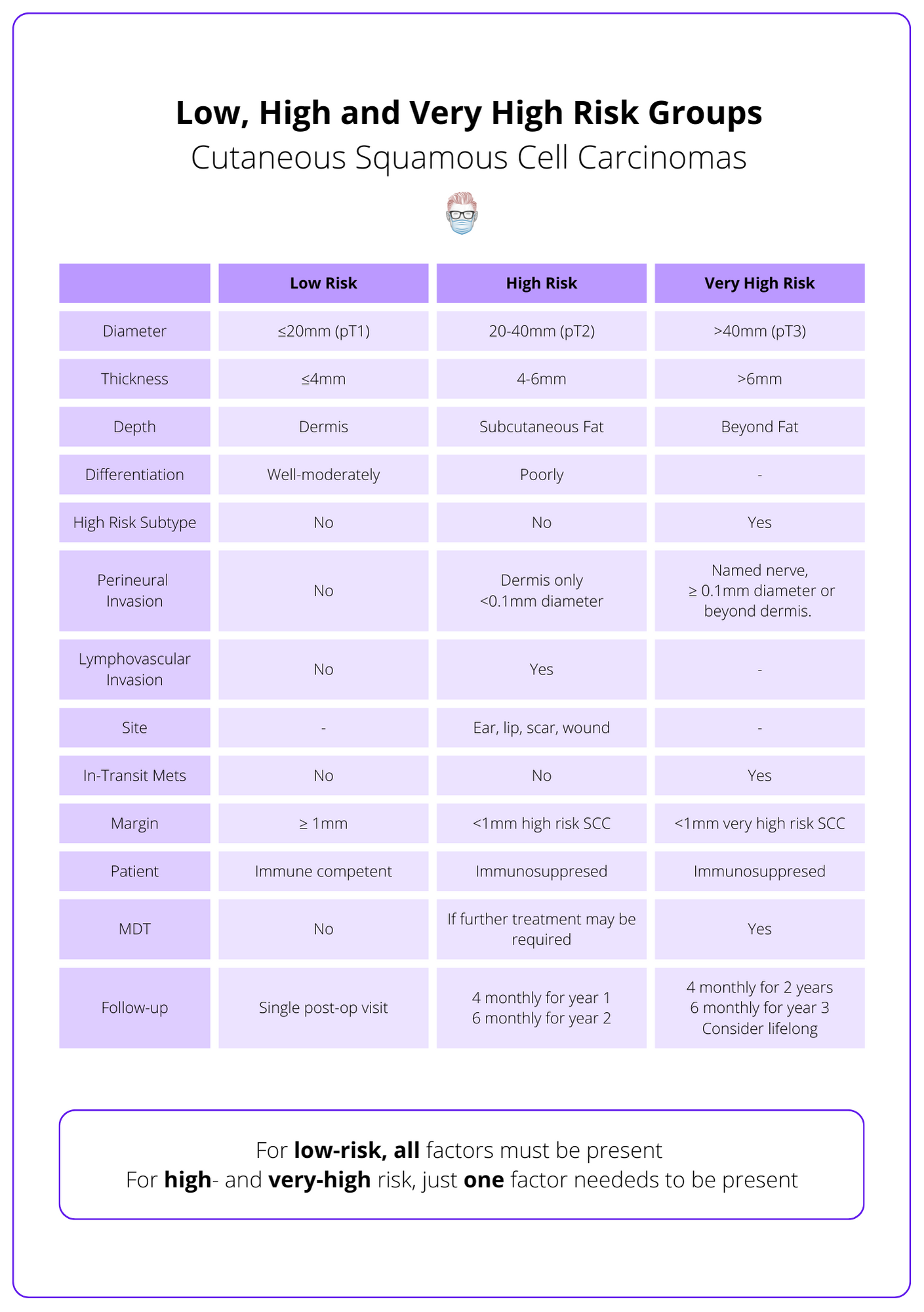

Risk Groups for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Risk Groups for Squamous Cell Carcinoma is a spectrum from low to very high risk based on TNM staging, patient status, and margin criteria.

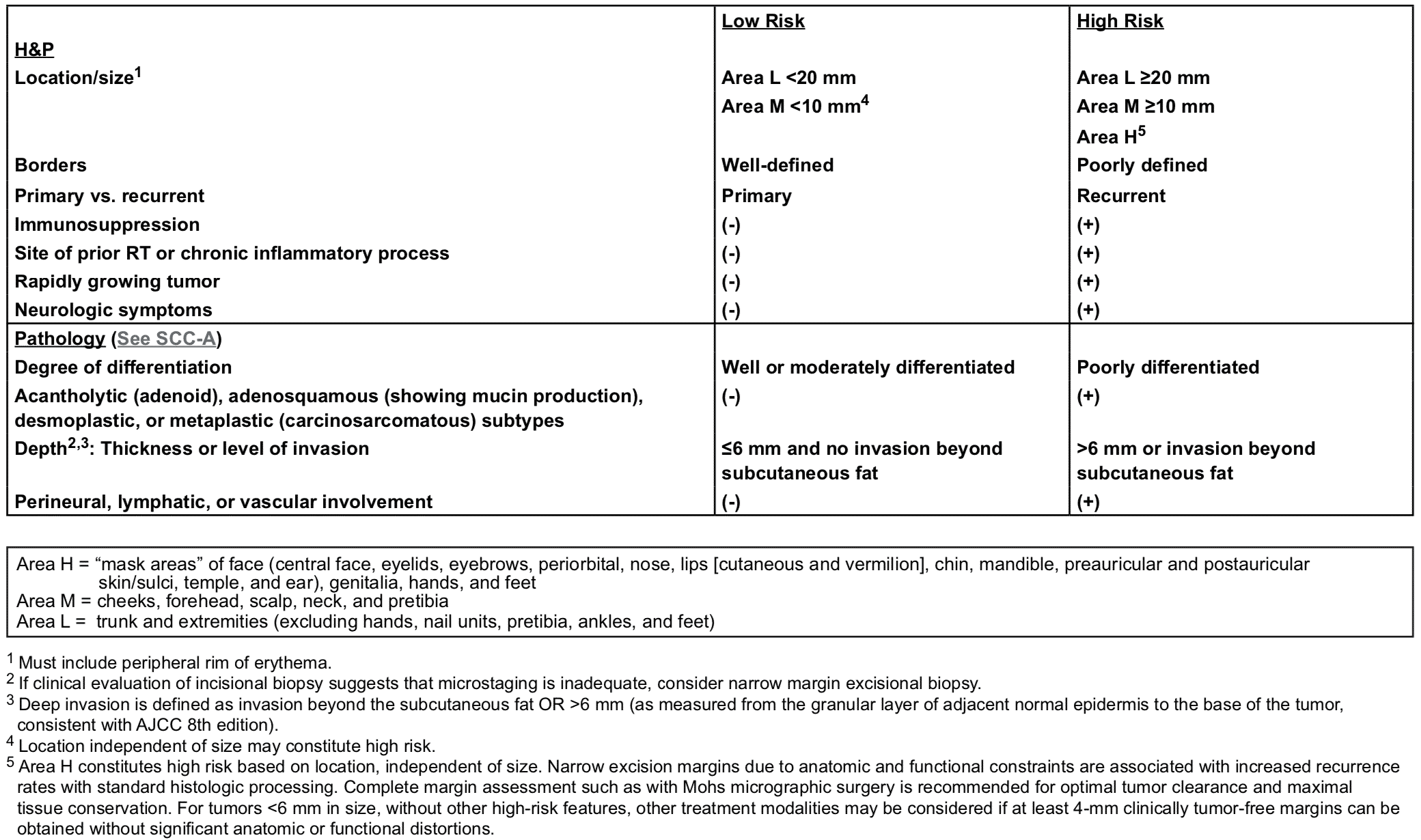

Risk assessment of the primary tumour guides treatment plan and follow-up for patients. NCCN, AJCC, and Brigham & Women’s Guidelines are commonly used (Marcil et al., 2000).

British Association of Dermatology 2021

The British Association of Dermatologies stratifies SCC into low-risk, high-risk, and very high-risk. These risk categories are determined by the patient, macroscopic and microscopic findings, as explained below (Keohane et al., 2021).

- Patient: immune status

- Macroscopic: site, size

- Microscopic: thickness, depth, PNI, LVI, differentiation, subtype

NCCN Risk Stratification

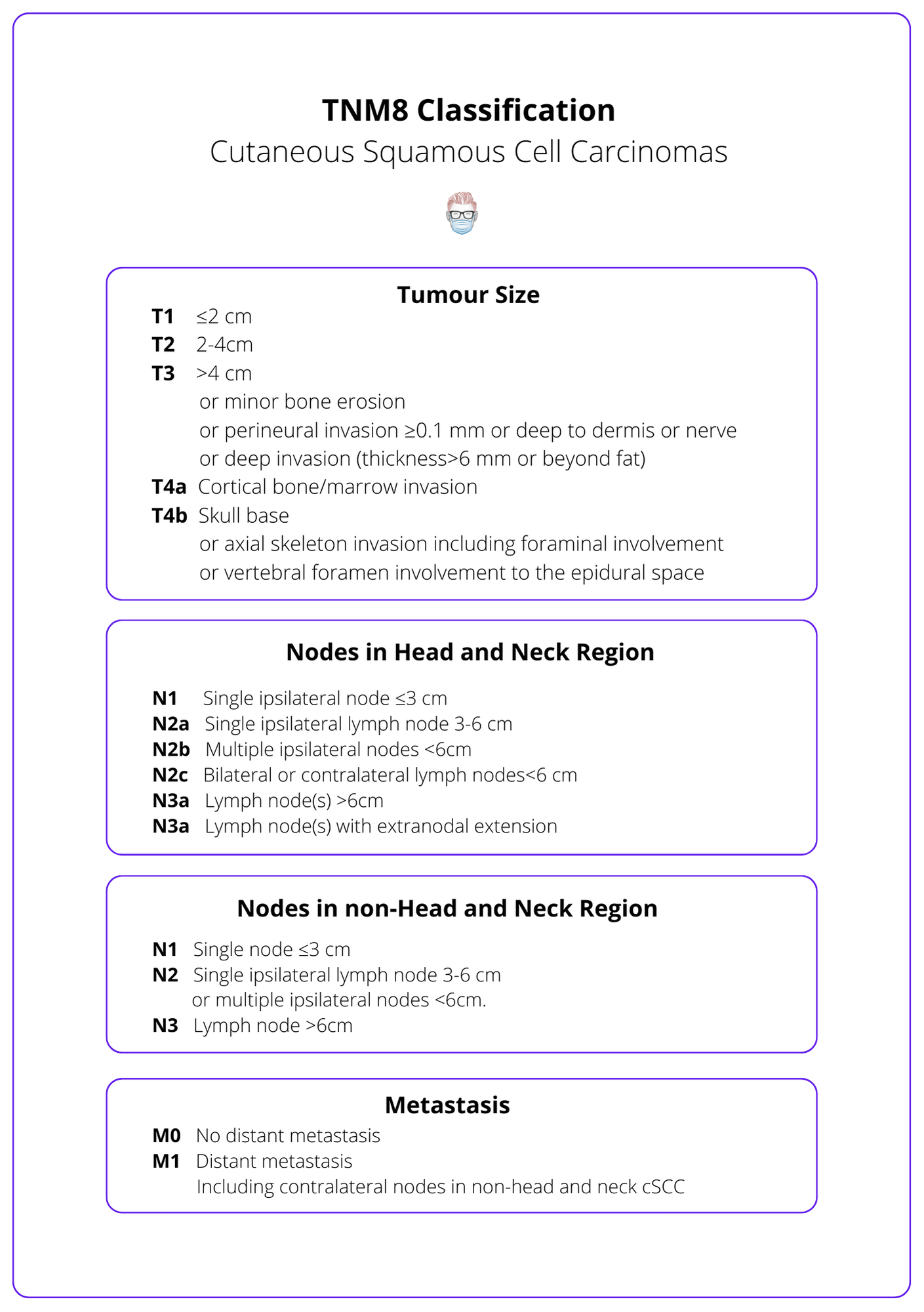

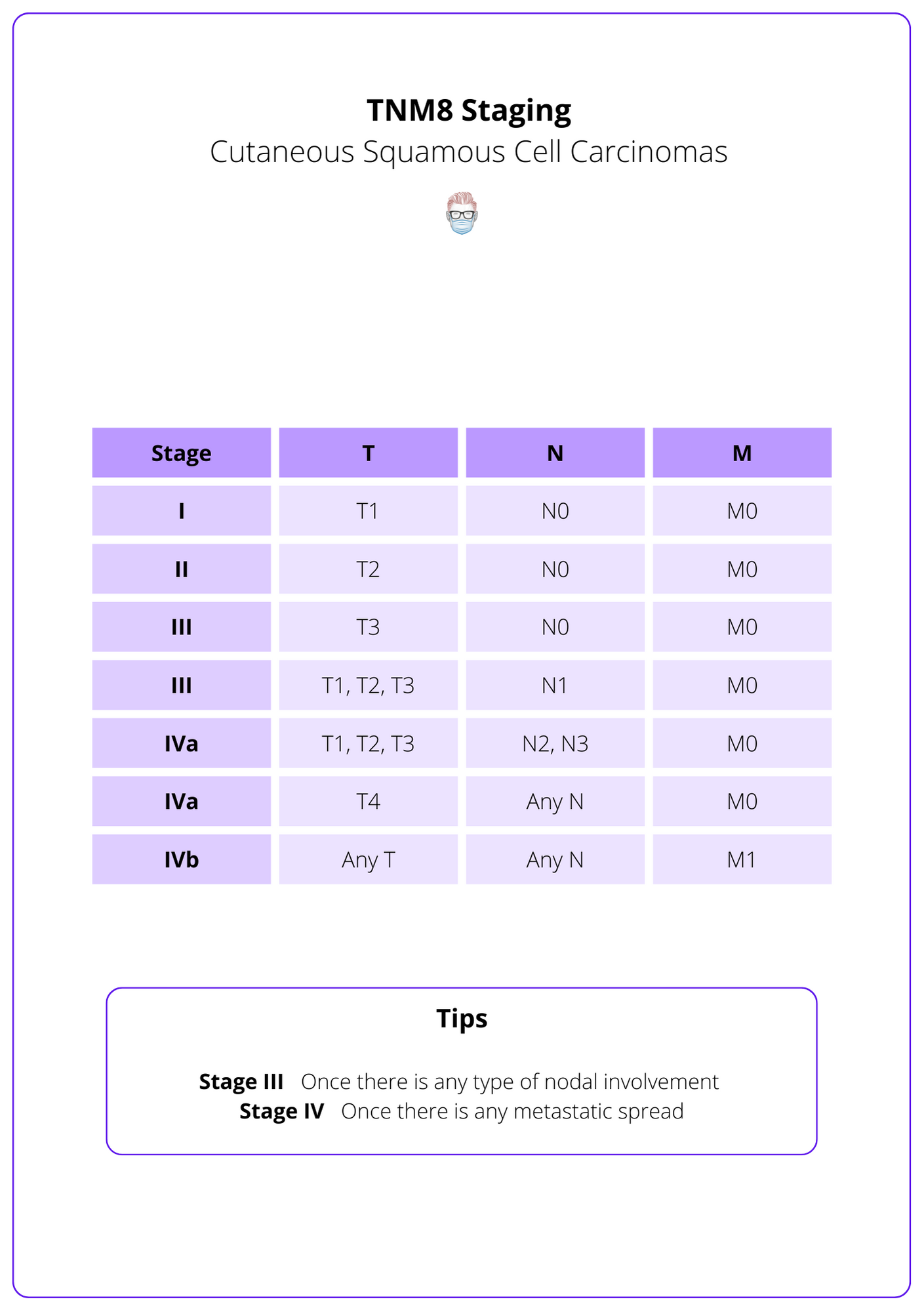

TNM Staging for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The TNM staging system is the internationally accepted classification of squamous cell carcinoma. It is based on tumour size, nodal status, and metastasis. The stage can be used to stratify risk, guide management, and predict outcomes.

Follow-Up for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

All patients have post-operative visits to confirm the diagnosis and education. Long-term follow-up based on tumour & patient risk status. This is guided by the BAD and NCCN guidelines.

Follow-up of patients with squamous cell carcinoma is based on the risk group and extent of the disease. 30%-50% of these patients will develop another SCC within 5 years and 70% of SCC recurrences occur within 2 years (Marcil et al., 2000 & Karagas et al., 1992).

All patients should have:

- An initial follow-up for education on the disease, self-examination, and sun protection.

- Involved a clinical nurse specialist.

- Discussion at the MDT if indicated.

- Examination of skin and lymph node basins.

British Association of Dermatology Guidelines:

- Low-Risk: one post-treatment review, safety net.

- High Risk: 4-monthly intervals for year 1, 6-monthly intervals for year 2.

- Very High Risk: 4-monthly for 2 years, 6-monthly for year 3.

- Metastatic: 3-monthly for 2 years, 6 monthly for years 3-5 (minimum).

Consider lifelong skin surveillance if likely to develop further high-risk SCCs (such as organ transplant recipients).

NCCN Guidelines

- Local: 3-12 months for 2 years, 6-12 months for 3 years, then annually.

- Regional:1-3 months in year 1, 2-4 months in year 2, 4-6 months in year 3, then 6-12 months for life.

Conclusion

1. Understanding of Squamous Cell Carcinoma: You now have a detailed understanding of the definition, classification, and anatomy of SCC, a common and potentially serious skin cancer.

2. Diagnostic Criteria for SCC: The article has equipped you with knowledge about the clinical and histological features that define SCC, aiding in its identification and distinction from other skin conditions.

3. Identified Risk Factors: You are now aware of the primary risk factors for SCC, including sun exposure, skin type, and immune status, which are crucial for assessing patient risk and tailoring prevention strategies.

4. Treatment Options for Squamous Cell Carcinoma: You have learned about the various treatment modalities for SCC, ranging from surgical interventions to radiation therapy and medical treatments, depending on the stage and severity of the disease.

5. Follow-Up Care: The article highlighted the importance of post-treatment follow-up, which is essential for managing recurrence risks and maintaining patient health.

Further Reading

- Keohane et al; British Association of Dermatologists’ Clinical Standards Unit. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma 2020. Br J Dermatol. 2021 Mar;184(3):401-414. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19621. PMID: 33150585.

- Xiang F, Lucas R, Hales S, Neale R. Incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in relation to ambient UV radiation in white populations, 1978-2012: empirical relationships. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(10):1063-1071. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.762

- Wu S, Han J, Laden F, Qureshi A. Long-term ultraviolet flux, other potential risk factors, and skin cancer risk: a cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(6):1080-1089. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0821

- Juzeniene A, Grigalavicius M, Baturaite Z, Moan J. Minimal and maximal incidence rates of skin cancer in Caucasians estimated by use of sigmoidal UV dose-incidence curves. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217(8):839-844. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.06.002

- Gallagher R, Hill G, Bajdik C, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentation factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. II. Squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(2):164-169. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7857112.

- Wehner M, Shive M, Chren M, Han J, Qureshi A, Linos E. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5909

- Box N, Duffy D, Irving R, et al. Melanocortin-1 receptor genotype is a risk factor for basal and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116(2):224-229. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01224.x

- Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(6):704-708. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3362

- Das K, Chakaraborty A, Rahman A, Khandkar S. Incidences of malignancy in chronic burn scar ulcers: experience from Bangladesh. Burns. 2015;41(6):1315-1321. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2015.02.008

- Kim C, Cheng J, Colegio O. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in solid organ transplant recipients: emerging strategies for surveillance, staging, and treatment. Semin Oncol. 2016;43(3):390-394. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.019

- Dika E, Fanti P, Misciali C, et al. Risk of skin cancer development in 672 patients affected by actinic keratosis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151(6):628-633.

- Glogau R. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 Pt 2):23-24. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.103339

- Eimpunth S, Goldenberg A, Hamman M, et al. Squamous Cell Carcinoma In Situ Upstaged to Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A 5-Year, Single Institution Retrospective Review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(5):698-703. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001028

- Kiprono S, Chaula B, Beltraminelli H. Histological review of skin cancers in African Albinos: a 10-year retrospective review. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:157. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-157

- Bradford P, Goldstein A, Tamura D, et al. Cancer and neurologic degeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum: long term follow-up characterises the role of DNA repair. J Med Genet. 2011;48(3):168-176. doi:10.1136/jmg.2010.083022

- ijsten TE, Stern RS. Oral retinoid use reduces cutaneous squamouscell carcinoma risk in patients with psoriasis treated with psoralen-UVA: a nested cohort study. JAmAcadDermatol2003;49:644–50.40 Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy Bet al. A phase 3 randomized trial ofnicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention.N Engl J Med2015;373:1618–26

- Wolberink E, Pasch M, Zeiler M, van E, Gerritsen M. High discordance between punch biopsy and excision in establishing basal cell carcinoma subtype: analysis of 500 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(8):985-989. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04628.x

- Haws A, Rojano R, Tahan S, Phung T. Accuracy of biopsy sampling for subtyping basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(1):106-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.042

- Griffiths R, Feeley K, Suvarna S. Audit of clinical and histological prognostic factors in primary invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: assessment in a minimum 5 year follow-up study after conventional excisional surgery. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55(4):287-292. doi:10.1054/bjps.2002.3833

- Rowe D, Carroll R, Day C. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976-990. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5

- Turner R, Leonard N, Malcolm A, Lawrence C, Dahl M. A retrospective study of outcome of Mohs’ micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma using formalin fixed sections. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(4):752-757. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03422.x

- Chren M, Linos E, Torres J, Stuart S, Parvataneni R, Boscardin W. Tumor recurrence 5 years after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(5):1188-1196. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.403

- Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, Stanton W, Leonardi-Bee J. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6153

- Marcil I, Stern R. Risk of developing a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(12):1524-1530. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1524

- Karagas M, Stukel T, Greenberg E, Baron J, Mott L, Stern R. Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1992;267(24):3305-3310.