Summary Card

Overview

An acute bacterial infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, characterized by erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness.

Pathogenesis

Bacteria breach the skin barrier, triggering an inflammatory cascade, with high-risk groups including IV drug users, diabetics, and immunocompromised patients.

Clinical Assessment

Poorly demarcated erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness. Systemic signs such as fever and lymphangitis indicate more severe infection.

Investigations

Diagnosed clinically, but imaging and laboratory tests may be required to detect abscesses, systemic toxicity, or deep infections.

Management

Management depends on severity and risk factors. Cephalexin is first-line for mild to moderate cases. Abscesses require incision & drainage, while severe cases may need IV antibiotics or surgical debridement.

Complications

Early complications include bacteremia, sepsis, and abscess formation, while late complications involve osteomyelitis.

Primary Contributor: Hatan Mortada, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Upper Limb Cellulitis

Upper limb cellulitis is an acute bacterial infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, characterized by erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness. Prompt antibiotic therapy is essential.

Cellulitis is an acute bacterial skin infection affecting the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. It is primarily caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci (Group A Streptococcus), followed by Staphylococcus aureus.

Classic features of upper limb cellulitis include (Stevens, 2014):

- Early: Erythemal, Warmth, Oedema, Tenderness (without abscess formation)

- Late: Abscess formation, Necrotizing fasciitis, Systemic sepsis

Annually, the U.S. sees 14 million cases resulting in 650,000 hospitalizations (Raff, 2016). In the U.K, the median hospital stay is three days (Sullivan, 2018).

Historically, red streaks (lymphangitis) were feared as “blood poisoning”, a term still used by some patients today.

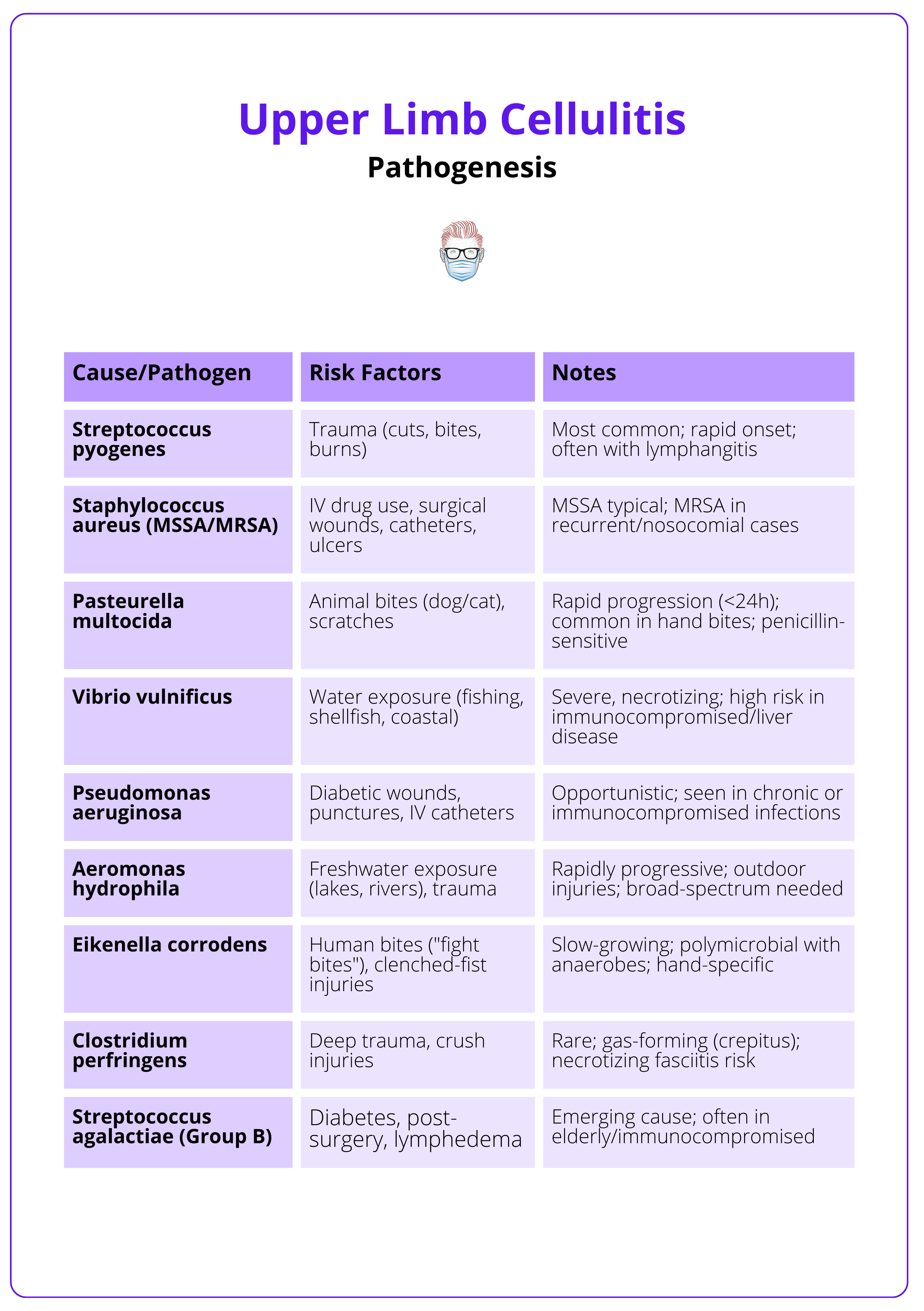

Pathogenesis of Upper Limb Cellulitis

Upper limb cellulitis develops when bacteria breach the skin barrier, triggering an inflammatory cascade, with high-risk groups including IV drug users, diabetics, and immunocompromised patients.

Upper limb cellulitis is most commonly caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus), followed by methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (Swartz, 2020).

The pathophysiology of upper limb cellulitis is explained below.

- Mechanism

Bacteria penetrate the dermis and subcutaneous tissue via a disrupted skin barrier, bypassing the protective role of the epidermis.

- Inflammatory Response

The infection triggers an acute inflammatory cascade with cytokine release, leading to vasodilation, edema, and neutrophil infiltration in the deep dermis and subcutaneous layers.

- Spread

In the upper limb, unchecked infection may extend along subcutaneous planes or lymphatics, potentially causing lymphangitis (visible red streaks) (Cruciani & De Lalla, 1998). Severe cases may progress to bacteremia or sepsis.

The table below summarises common pathogens and associated risk factors for upper limb cellulitis, highlighting key clinical notes for rapid identification and management.

Animal bites on the hand can introduce Pasteurella multocida, causing rapid-onset cellulitis. Recurrent cellulitis in the upper limb should raise suspicion for chronic lymphedema.

Clinical Assessment of Upper Limb Cellulitis

Upper limb cellulitis is characterized by poorly demarcated erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness. Systemic signs such as fever and lymphangitis indicate more severe infection.

Clinical assessment of upper limb cellulitis includes taking detailed history, physical examination, and special tests.

History

- Onset & Progression: Sudden or gradual spread of erythema, warmth, and swelling.

- Associated Symptoms: Malaise, fatigue, fever, and chills.

- Precipitating Factors: Recent trauma, insect/animal bites, IV drug use, or prior skin infections.

- Medical History: Diabetes, venous insufficiency, lymphedema, or prior cellulitis episodes are risk factors.

- Travel & Exposure: History of immersion injuries, bites, or recent surgery.

Certain anatomical regions of cellulitis have been associated with specific triggers.

- Lower Limbs (most common): Venous insufficiency, lymphedema, trauma.

- Upper Limbs: IV drug use, post-surgical wounds, bites.

- Face & Periorbital Region: Dental infections, sinusitis, preseptal cellulitis.

- Trunk & Abdomen: Post-surgical infections, obesity-related skin folds.

- Breast: Mastitis in lactating women, post-surgical infections.

Examination

- Local Signs: Poorly demarcated erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness.

- Systemic Signs: Fever, tachycardia, and lymphadenopathy (suggesting systemic involvement).

- Skin Breakdown: Look for wounds, fissures, ulcers, or surgical sites.

- Complications: Presence of bullae, vesicles, or peau d’orange may indicate severe infection.

Special Tests

- Marking Borders: Use a skin marker to outline the erythema’s edge — monitor spread and treatment response.

- Two-of-Four Criteria: Confirm diagnosis with at least two of: warmth, erythema, edema, or tenderness (per clinical guidelines).

- Lymph Node Palpation: Gently palpate axillary lymph nodes for enlargement or tenderness, indicating lymphatic involvement.

- Abscess Exclusion: Apply gentle pressure to detect fluctuance; if present, consider ultrasound to differentiate from simple cellulitis.

The image below illustrates the clinical presentation of upper limb cellulitis.

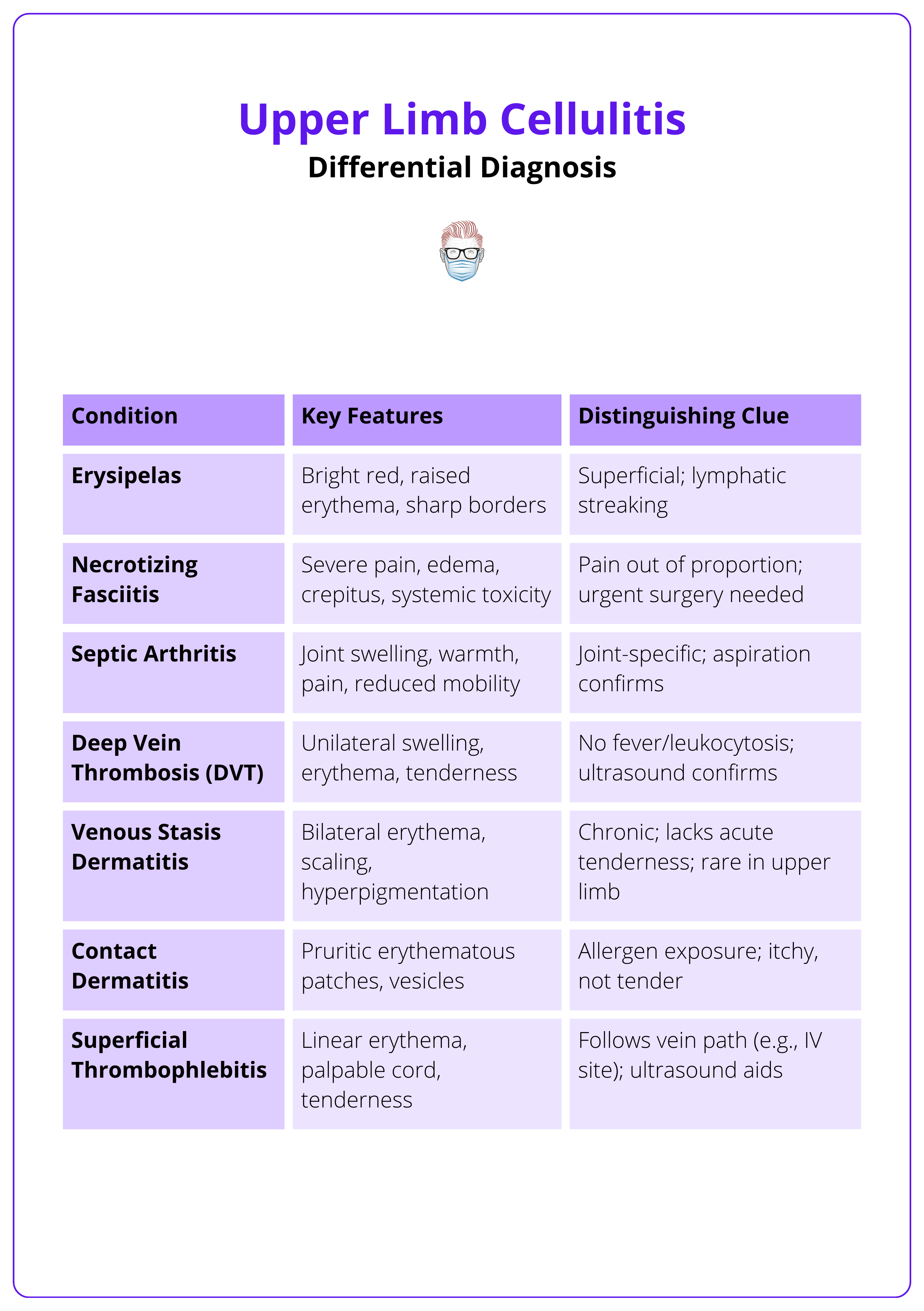

Differential Diagnosis

- Erysipelas: Superficial Streptococcus pyogenes infection with bright red, well-demarcated erythema; may show lymphatic streaking. Less common in the upper limb but possible post-trauma.

- Venous Stasis Dermatitis: Chronic venous insufficiency causing bilateral erythema, scaling, edema, and hyperpigmentation. Unlike cellulitis, it lacks acute tenderness and warmth.

- Necrotizing Fasciitis: Rapidly spreading deep soft tissue infection with severe pain disproportionate to findings, crepitus, and systemic toxicity. CT may show subcutaneous gas. Surgical emergency.

- Septic Arthritis: Joint infection (e.g., elbow, wrist) with localized swelling, warmth, pain, and reduced mobility. Unlike cellulitis, it remains joint-specific. Confirmed by joint aspiration.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Upper limb venous thrombus presenting with unilateral swelling, erythema, warmth, and tenderness. No fever or leukocytosis. Confirmed via ultrasound.

The table below summarises these conditions, their features, and their distinct qualities.

Bilateral cellulitis is uncommon → Consider venous stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis instead.

Investigations for Upper Limb Cellulitis

Upper limb cellulitis is diagnosed clinically, but imaging and laboratory tests may be required to detect abscesses, systemic toxicity, or deep infections.

Investigations including bloods and imaging for upper limb cellulitis are as follows.

Blood Work

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated WBC, CRP, and ESR suggest infection but are nonspecific.

- Blood Cultures: Only indicated in immunocompromised patients, systemic toxicity, or extensive disease (positive in <5% of cases) (Torres, 2017).

- Serologic Tests: Antistreptolysin O (ASO) and anti-DNase B titers can confirm recent streptococcal infection in recurrent cellulitis.

Imaging

- Ultrasound: Differentiates cellulitis vs. abscess → Abscess appears as a hypoechoic fluid collection requiring drainage.

- X-ray: Rules out foreign bodies or gas-forming infections (e.g., necrotizing fasciitis).

- CT Scan: Indicated for deep infections, extensive soft tissue involvement, or suspected necrotizing fasciitis (findings: fascial thickening, gas formation).

- MRI: Best for detecting deep tissue involvement (e.g., osteomyelitis or fasciitis) but reserved for unclear cases.

Other Tests

- Wound Cultures: Only needed if purulent drainage or unusual infection is suspected (e.g., animal bites, immunosuppression).

- Biopsy: Rarely performed but may be indicated for chronic, non-resolving cellulitis to rule out vasculitis or malignancy.

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging for suspected abscess, while CT is preferred for deep infections or necrotizing fasciitis.

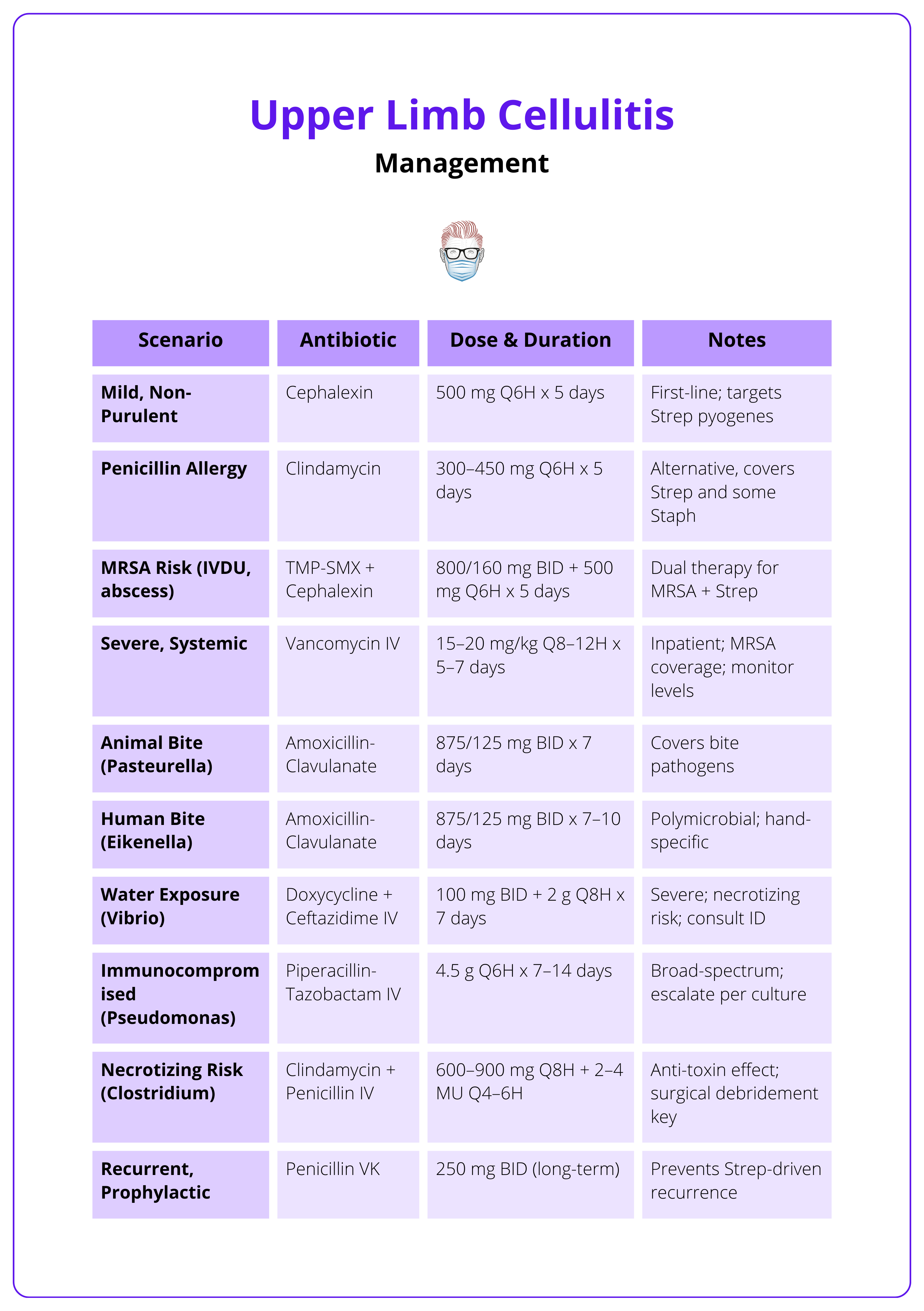

Management of Upper Limb Cellulitis

Management depends on severity and risk factors. Cephalexin is first-line for mild to moderate cases. Abscesses require incision and drainage, while severe cases may need IV antibiotics or surgical debridement.

Treatment depends on severity and risk factors. First-line is cephalexin 500 mg every 6 hours for 5 days is first-line for mild to moderate cases. Clindamycin is used in penicillin-allergic patients, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is added for MRSA risk.

Abscesses require incision and drainage, while severe cases may need IV antibiotics or surgical debridement.

Outpatient (Mild to Moderate Cellulitis)

- First-Line (Non-Purulent Cellulitis): Cephalexin 500 mg every 6 hours for 5 days (longer if slow improvement) (Gibbons, 2017).

- Beta-Lactam Allergy: Clindamycin 300–450 mg every 6 hours (Gibbons, 2017).

- MRSA Risk Factors (IV drug use, abscess, puncture wounds): Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 800/160 mg twice daily + Cephalexin (Gibbons, 2017).

- Supportive Care: Limb elevation, hydration, and analgesia.

Inpatient (Severe or Complicated Cases)

Indications for hospitalisation include,

- Systemic signs of infection (fever >38°C, tachycardia, hypotension).

- Rapidly spreading erythema or failure of outpatient therapy.

- Immunocompromised patients (diabetes, chemotherapy, chronic illness).

- Cellulitis near an indwelling medical device (e.g., prosthetic joints, vascular catheters).

IV Antibiotics

It is important to consult your local hospital guidelines. Suggestions include,

- No MRSA Risk: Cefazolin IV, then switch to Cephalexin PO once stable.

- MRSA Risk: Vancomycin IV, then step down to TMP-SMX PO.

- Immunocompromised/Broad-Spectrum Needed: Vancomycin + Piperacillin-Tazobactam IV.

Special Considerations

- Abscess or Purulent Lesions: Incision & drainage, with culture-guided antibiotics.

- Animal Bites: Cover Pasteurella multocida (Amoxicillin-Clavulanate).

- Water-Related Injuries: Cover Vibrio vulnificus (doxycycline + ceftazidime).

- Diabetic Hand Infections: Consider Pseudomonas aeruginosa coverage.

The table below summarises antibiotic regimens for upper limb cellulitis, stratified by clinical scenario, pathogen coverage, and treatment duration.

If cellulitis fails to improve within 48–72 hours, reassess for abscess, resistant organisms, or alternative diagnoses (DVT, necrotizing fasciitis, etc.).

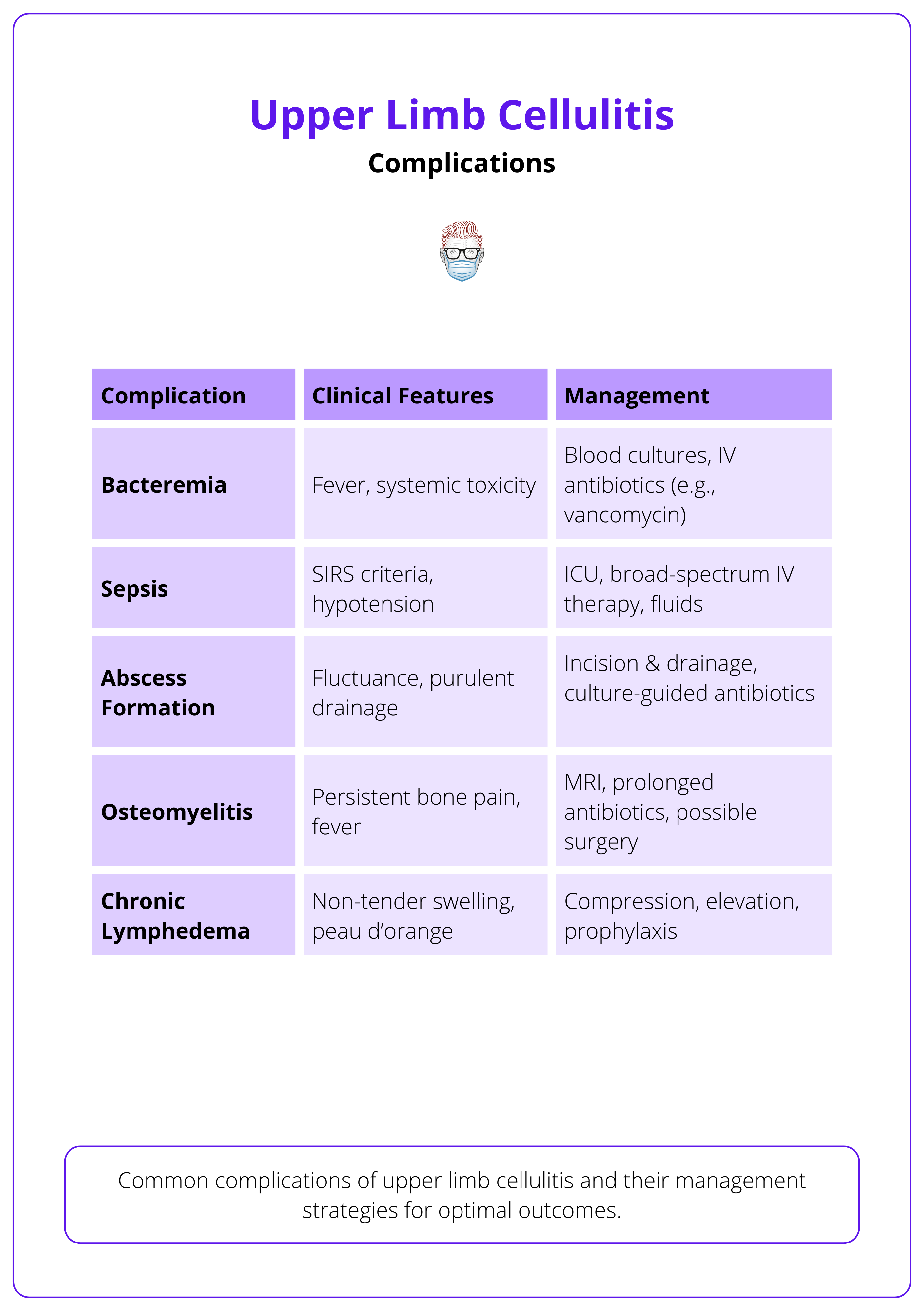

Complications of Upper Limb Cellulitis

Early complications include bacteremia, sepsis, and abscess formation, while late complications involve osteomyelitis and chronic lymphedema. Symptoms improve within 48 hours with treatment, with full recovery in 5–7 days.

Early complications include bacteremia, sepsis, and abscess formation, while late complications include osteomyelitis and chronic lymphedema. With appropriate treatment, symptoms improve within 48 hours, and full recovery occurs within 5-7 days. Recurrence rates range from 8–20% annually if risk factors persist.

Expected Prognosis

Recovery Time

With prompt diagnosis and correct antibiotics, signs (erythema, tenderness) typically improve within 48 hours; full resolution often occurs within 5–7 days for uncomplicated cases (Raff, 2016).

Recurrence Rates

Annual recurrence affects 8–20% of patients, with lifetime rates up to 49%, especially if risk factors (e.g., lymphedema, IV drug use) persist; preventable with wound care and hygiene (Richmond, 2014) (Raff, 2016).

Treatment Success

Initial antibiotic failure occurs in ~18% of cases, but the overall prognosis remains good with timely management (Obaitan, 2016).

Complications

Early

- Bacteremia: Bacteria enter the bloodstream (diagnosed via blood cultures in systemic cases), risking systemic spread if untreated.

- Sepsis: Occurs with two or more SIRS criteria (fever >38°C, tachycardia >90 bpm, tachypnea >20 breaths/min, abnormal WBC); requires urgent IV antibiotics.

- Abscess Formation: Progression to purulent collections needing drainage, more common with MRSA or delayed treatment.

Late

- Osteomyelitis: Infection spreads to the bone (e.g., radius/ulna in upper limb), necessitating prolonged antibiotics and possible surgery.

- Endocarditis: Rare but severe; bacteremia infects the heart’s endocardium, requiring extended treatment.

- Lymphatic Damage: Recurrent episodes or severe infection may cause chronic lymphedema, impairing arm function (Brandon, 2023).

The table below summarises complications of upper limb cellulitis and their management.

Lymphatic damage = Chronic swelling → Repeated cellulitis episodes increase the risk of permanent lymphedema, making future infections more frequent and severe.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Upper limb cellulitis is an acute bacterial infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, presenting with erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness. Prompt antibiotic therapy prevents complications.

2. Aetiology & Pathophysiology: Most cases are caused by Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus, often entering through skin breaks (e.g., trauma, IV drug use, bites). Bacterial invasion triggers an inflammatory response, leading to vasodilation, edema, and neutrophil infiltration.

3. Clinical Features & Differential: Patients present with poorly demarcated erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness. Fever and lymphangitis indicate severe infection. Differentials include erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis, septic arthritis, and DVT.

4. Diagnosis & Investigations: Clinical diagnosis is key. Ultrasound helps differentiate cellulitis from abscesses. Blood cultures are reserved for systemic signs, while CT scans assess deep infections or necrotizing fasciitis.

5. Management: Cephalexin (500 mg q6h for 5 days) is first-line; clindamycin is an alternative for penicillin allergies. Add trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for MRSA risk. Abscesses require incision and drainage, while severe cases need IV antibiotics and possible debridement.

6. Complications & Prognosis: Early risks include bacteremia, sepsis, and abscess formation; late risks include osteomyelitis and chronic lymphedema. Symptoms improve within 48 hours, with full recovery in 5–7 days. Recurrence rates range from 8–20% annually in high-risk patients.

Further Reading

- Brown BD, Hood Watson KL. Cellulitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549770/

- Parikh RP, Pappas-Politis E. Soft tissue infection of the upper extremity. Eplasty. 2011;11:ic6. Published 2011 Apr 11.

- Sullivan T, de Barra E. Diagnosis and management of cellulitis. Clin Med (Lond). 2018;18(2):160-163. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.18-2-160

- Spelman D, Baddour LM, Nelson S, Hall KK. Acute cellulitis and erysipelas in adults: Treatment. UpToDate. Updated December 12, 2024. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-cellulitis-and-erysipelas-in-adults-treatment

- Burian, E.A., Franks, P.J., Borman, P. et al. Factors associated with cellulitis in lymphoedema of the arm – an international cross-sectional study (LIMPRINT). BMC Infect Dis 24, 102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08839-z

- Ortiz-Lazo E, Arriagada-Egnen C, Poehls C, Concha-Rogazy M. An update on the treatment and management of cellulitis. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110(2):124-130. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2019.01.011

- Lim SH, Tunku Ahmad TS, Devarajooh C, Gunasagaran J. Upper limb infections: A comparison between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022;30(1). doi:10.1177/23094990221075376

- Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: A Review. JAMA. 2016;316(3):325-337. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8825