Summary Card

Overview

Upper eyelid reconstruction is a complex surgical procedure aimed at restoring function and aesthetics following defects caused by trauma, tumors, burns, or congenital anomalies.

Upper Eyelid Anatomy

The upper eyelid consists of three structural layers — anterior, middle, and posterior lamellae — each contributing to mobility, stability, and function.

Reconstruction Principles

Reconstruction must restore the eyelid's lamellar structure, protect the cornea, prevent tension, and maintain aesthetic symmetry.

Partial Thickness Defects

Small defects (<25%) are treated with direct closure or skin grafts, while larger defects (>25%) require local flaps for optimal reconstruction.

Full-Thickness Defects

Small defects (<25%) can be closed in layers, while larger defects (>25%) require flaps and posterior lamella grafts for structural stability.

Complications & Management

Complications can affect both functional and aesthetic outcomes, requiring additional interventions. These can be broadly classified into early and late complications.

Primary Contributor: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Upper Eyelid Reconstruction

Upper eyelid reconstruction requires re‐establishing both the functional and aesthetic aspects of the upper eyelid through a tailored, layered approach.

Upper eyelid reconstruction is challenging because of the eyelid’s complex anatomy and dual roles. It is essential to rebuild both its protective functions—such as safeguarding the eye and distributing tears—and its contribution to facial expression and aesthetics (Dhar, 2016).

Defects that require reconstruction can be:

- Congenital: Colobomas, dermoids, and other birth defects (Morley, 2010)

- Acquired: Trauma, cancers, burns

The image below illustrates a left upper eyelid malignancy.

Anatomy of the Upper Eyelid

The upper eyelid is made up of two main layers — the anterior and posterior lamellae — each essential for mobility, stability, and function.

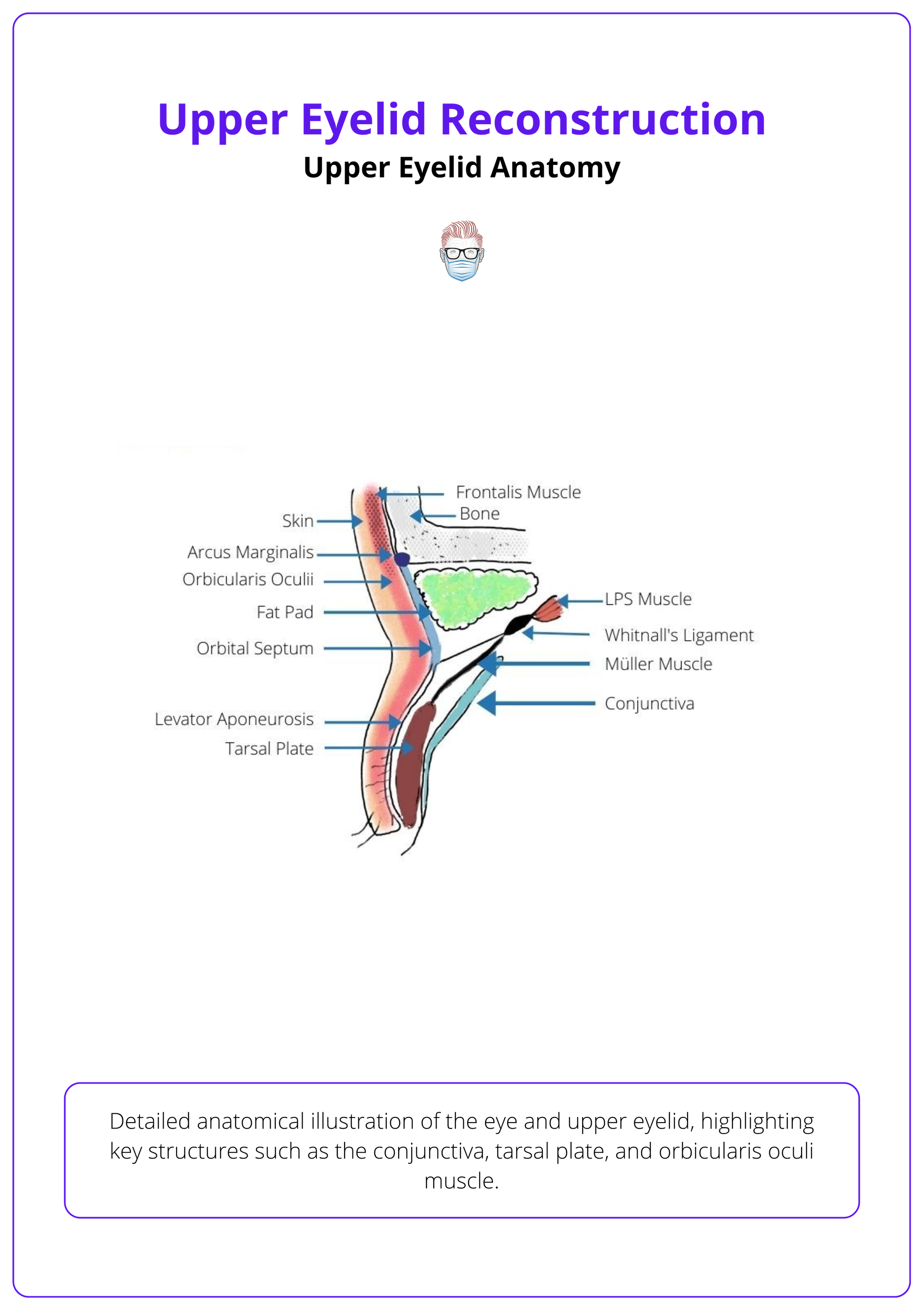

The upper eyelid is traditionally described as a two-layer structure: an anterior lamella and a posterior lamella. The septum, which separates these layers, is sometimes referred to as the middle lamella.

Anterior Lamella is composed of skin and orbicularis oculi muscle.

- Skin: thinnest in the body (~1 mm) (Janis, 2022). Precise tissue matching is required to avoid contracture (Kakizaki et al., 2009).

- Muscle: orbicularis oculi aids in eyelid closure and supports the tear pump mechanism (Dhar, 2016). It is innervated by the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve.

Posterior Lamella is composed of the tarsal plate and conjunctiva.

- Tarsal Plate: Provides structural support, measuring ~25 mm in length, 1 mm thick, and 7–12 mm vertically. It houses the meibomian glands and supports the insertion of the levator aponeurosis and Müller’s muscle (DiFrancesco et al., 2004).

- Conjunctiva: Consists of palpebral, bulbar, and fornices.

The image below illustrates upper eyelid anatomy.

Other Anatomical Eyelid Structures

- Levator Aponeurosis: Elevates the eyelid (allowing 10–15 mm movement) and forms the upper eyelid crease by inserting into the pretarsal dermis (Morley, 2010). It is innervated by the oculomotor nerve.

- Müller’s Muscle: Provides an extra 1–2 mm of eyelid elevation through sympathetic innervation.

- Medial Canthal Tendon: Helps maintain eyelid position and tear drainage; its disruption can cause medial ectropion or telecanthus (Mathijssen & van der Meulen, 2010).

- Lateral Canthal Tendon: Stabilizes the lateral lid margin by anchoring to Whitnall’s tubercle. Weakness or disruption can compromise globe protection, cause exposure keratopathy, and impair tear drainage (Suryadevara, 2009).

The upper eyelid's blood supply comes from the ophthalmic artery, with both marginal and peripheral arcades ensuring strong vascularity.

Preoperative Assessment

Key Point

A comprehensive evaluation should focus on the patient's overall status, oncological margins when relevant, and structural involvement.

Pre-operative assessment should be centred on a patient's history and examination of their eyelid.

History

- Document comorbidities (e.g., smoking, prior surgeries, radiation, medications such as anticoagulants).

- For malignancy-related defects, ensure clear surgical margins before reconstruction (O’Donnell & Mannor, 2009; Mathijssen & van der Meulen, 2010).

Physical Examination

Assess the depth of the planned defect and identify any structural involvement.

- Tissue Quality: Assess tissue quality regarding vascularity, scarring, radiation damage, and laxity.

- Tarsus: Assess the remaining tarsus and determine if one or both lamellae need reconstruction.

- Canthal Tendons: Evaluate canthal support and the lacrimal drainage system, especially in medial defects.

- Vision: Test visual acuity and obtain an ophthalmologic consultation if necessary.

In trauma situations, identify any peripheral zones of injury; traumatic avulsions may compromise canalicular integrity, often necessitating secondary lacrimal reconstruction.

Principles of Upper Eyelid Reconstruction

Reconstruction must restore the eyelid’s layered structure, protect the cornea, ensure a tension-free repair, and maintain aesthetic symmetry.

Balancing functionality and aesthetics is crucial in upper eyelid reconstruction. Key principles include,

- Adhered to the Reconstructive Ladder: Begin with the simplest technique and progress to more complex methods as needed (Spinelli & Jelks, 1993).

- Restore Lamellar Structure & Separation: Replacing tissue with "like for like" to maintain mobility and integrity (Alghoul et al., 2013). For the anterior lamella, skin grafts or flaps are used, while the posterior lamella is reconstructed with tarsus, conjunctiva, or mucosal grafts.

- Tension: A tension-free closure is essential to avoid lid malposition. Achieving symmetry with the contralateral eyelid is critical.

- Blood Supply: Ensure a well-perfused recipient bed by pairing nonvascularized grafts with vascularized flaps.

- Consider Patient Factors: Elderly patients often have lax skin, allowing for more extensive direct closures.

- Corneal Protection: Maintain proper lid-globe contact to prevent exposure keratopathy and corneal abrasion.

It is important to have a stepwise approach to eyelid reconstruction. For example,

- For small defects, begin with direct closure when tissue laxity permits and tension is minimal.

- If direct closure is not feasible, progress to local flaps—such as the Tenzel semicircular flap—which offer additional tissue mobilization while preserving adjacent structures.

- For bilamellar defects, consider using separate grafts or flaps for the anterior and posterior lamellae.

- Finally, for extensive or complex defects where local tissue is insufficient, lid-sharing procedures can be employed to achieve optimal functional and aesthetic outcomes.

Partial Thickness Defects of the Upper Eyelid

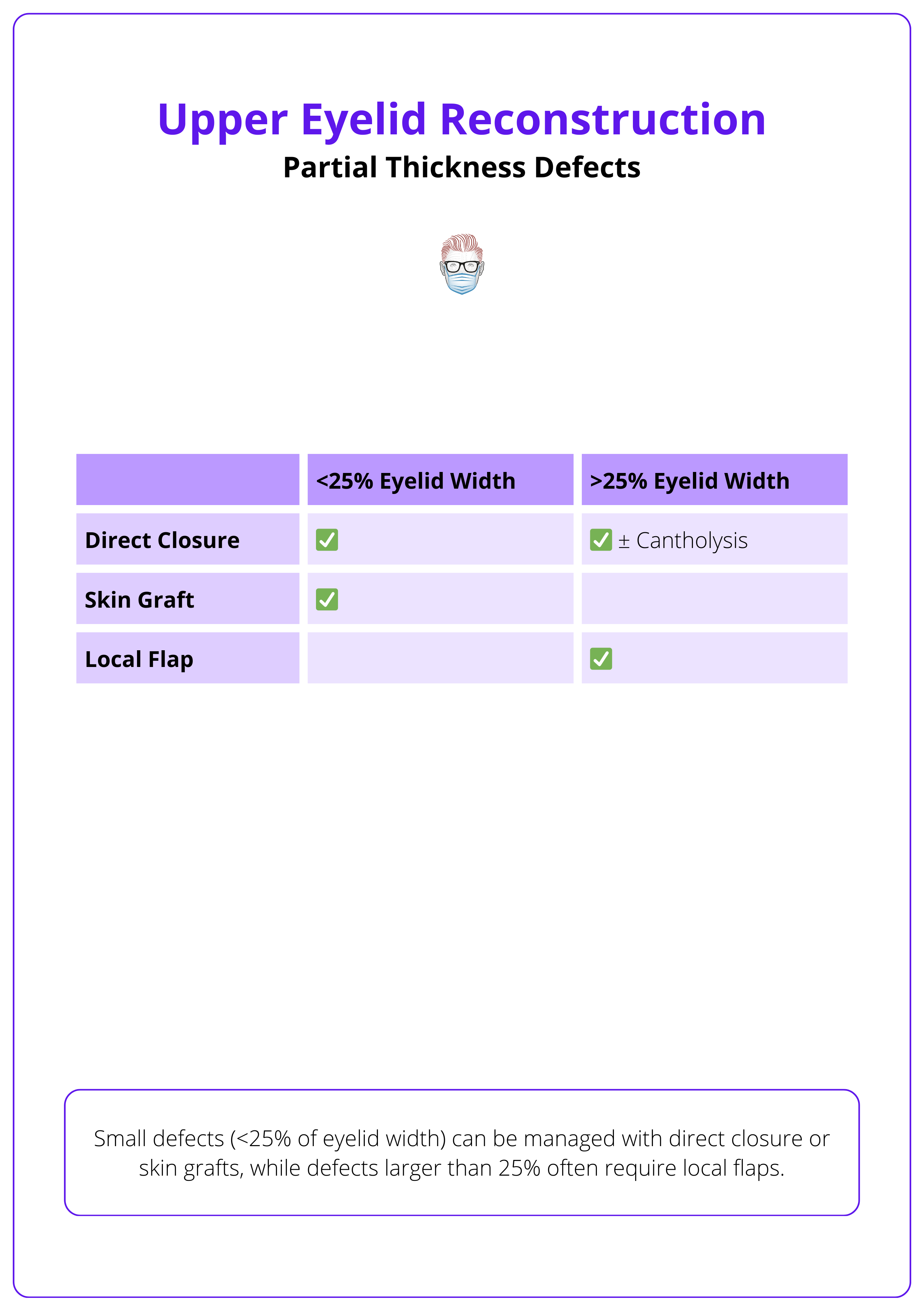

Small defects (<25% of eyelid width) can be managed with direct closure or skin grafts, while defects larger than 25% often require local flaps.

Partial-thickness defects affect only the anterior lamella—the skin and orbicularis muscle. The choice of reconstruction depends on the defect’s size, location (central, medial, or lateral), and the availability of nearby tissue.

The table below summarizes eyelid width and treatment options.

<25% of the Eyelid Width

For small defects, two main options are used.

- Direct Closure

- Indication: Defects up to 25-30%, cantholysis can extend this to 50%. (McCord & Codner, 2008).

- Benefit: Efficient, single-surgery that preserves mobility (Codner, 2010).

- Technique: Often a wedge excision to avoid dog-ear deformities

- Skin Grafts

Avoid split-thickness grafts, as they have higher contraction rates; use quilting sutures to improve graft adherence and minimize hematoma risk. (Verity, 2004).

>25% Eyelid Width

For larger defects, more advanced techniques are often required:

- Direct Closure with Cantholysis

- Indication: If significant skin laxity, releasing the lateral canthal tendon can allow primary closure of defects up to 50% (Dhar, 2016).

- Benefit: Tension-free closure while maintaining the natural contour of the eyelid.

- Tenzel Semi-Circular Flap

- Indication: Partial or full-thickness defects involving 25–60% of the eyelid’s horizontal width

- Technique: This technique uses a semicircular incision from the lateral canthus into the temporal region. The flap is elevated in a submuscular plane and advanced medially, with or without lateral cantholysis

- Advantages: Tension-free closure, preserves eyelid contour, avoids occluding the visual axis, and is usually performed in a single stage.

- Disadvantages: Requires sufficient tissue laxity and improper repair can lead to lateral canthal malposition. (Verity, 2004).

Intra-Operative Video of Tenzel Flap

Other Local Flaps

- Hinged blepharoplasty flap can be utilised in medial defects. It mobilizes skin from the upper eyelid using classic blepharoplasty incisions.

- Non-marginal defects of the upper eyelid that cannot be closed directly are usually closed using local advancement or rotation flaps (Harmon, 2023).

The marginal arcade lies only 2–3 mm from the eyelid margin, making it vulnerable during surgery.

Full-Thickness Defects of the Upper Eyelid

Small defects (<25% of eyelid width) can be repaired by closing the layers directly, whereas larger defects (>25%) require flaps and posterior lamella grafts for proper structural support.

Full-thickness defects affect all eyelid layers—skin, muscle, tarsus, and conjunctiva—and require a layered reconstruction to restore both function and appearance.

Small Defects (<25%)

Small defects can often be closed directly, whereas larger defects typically need flaps or posterior lamella grafts. In relation to the direct closure of full-thickness defects,

- Suitable if good lid laxity.

- Achieved by approximating the conjunctiva, tarsus, and skin in layers

- May require cantholysis and canthopexy (Jennings, 2020).

Larger Defects (>25%)

- Cutler-Beard flap is indicated in full-thickness upper eyelid defect >50%.

- Technique: A full-thickness rectangular flap—including skin, orbicularis, and conjunctiva—is harvested from the lower eyelid and sutured into the defect. 3-6 weeks later, a second-stage flaps division restores independent eyelid function (Jennings, 2020).

- Advantages: Reliable for reconstructing large defects.

- Disadvantages: Two-stage procedure, Temporary occlusion of the visual axis, risk of ectropion or lower eyelid retraction.

- Lid Switch Flap is indicated in total eyelid defects or 50–75% of the lid.

- Technique: A semicircular rotation flap is raised from the lower eyelid to replace the missing tissue. (Jennings, 2020).

- Advantages: Provides composite tissue to reconstruct both the anterior and posterior lamellae

- Disadvantages: Requires a second-stage separation; risks include donor site complications such as lower eyelid retraction or ectropion.

- Fricke Flap is indicated in large anterior lamellar defects or full-thickness defects requiring robust skin coverage.

- Technique: A two-stage procedure using a temporal skin flap based on the superficial temporal artery. The flap is transposed to cover the defect and later divided once healing is complete (Codner, 2010).

- Advantages: Provides durable skin with excellent vascularity.

- Disadvantages: Can result in a bulky donor site and aesthetic mismatch with adjacent tissue.

Reinforce the canthal tendons during full-thickness reconstructions to enhance stability and prevent malposition (Suryadevara, 2009).

Posterior Lamella Reconstruction

Reconstructing the posterior lamella is essential for restoring eyelid stability by replicating the rigidity of the tarsus. For optimal healing, the graft must be placed on a well-vascularized recipient bed while preserving the integrity of the mucosal and cartilage/tarsal structures.

Options for reconstruction include,

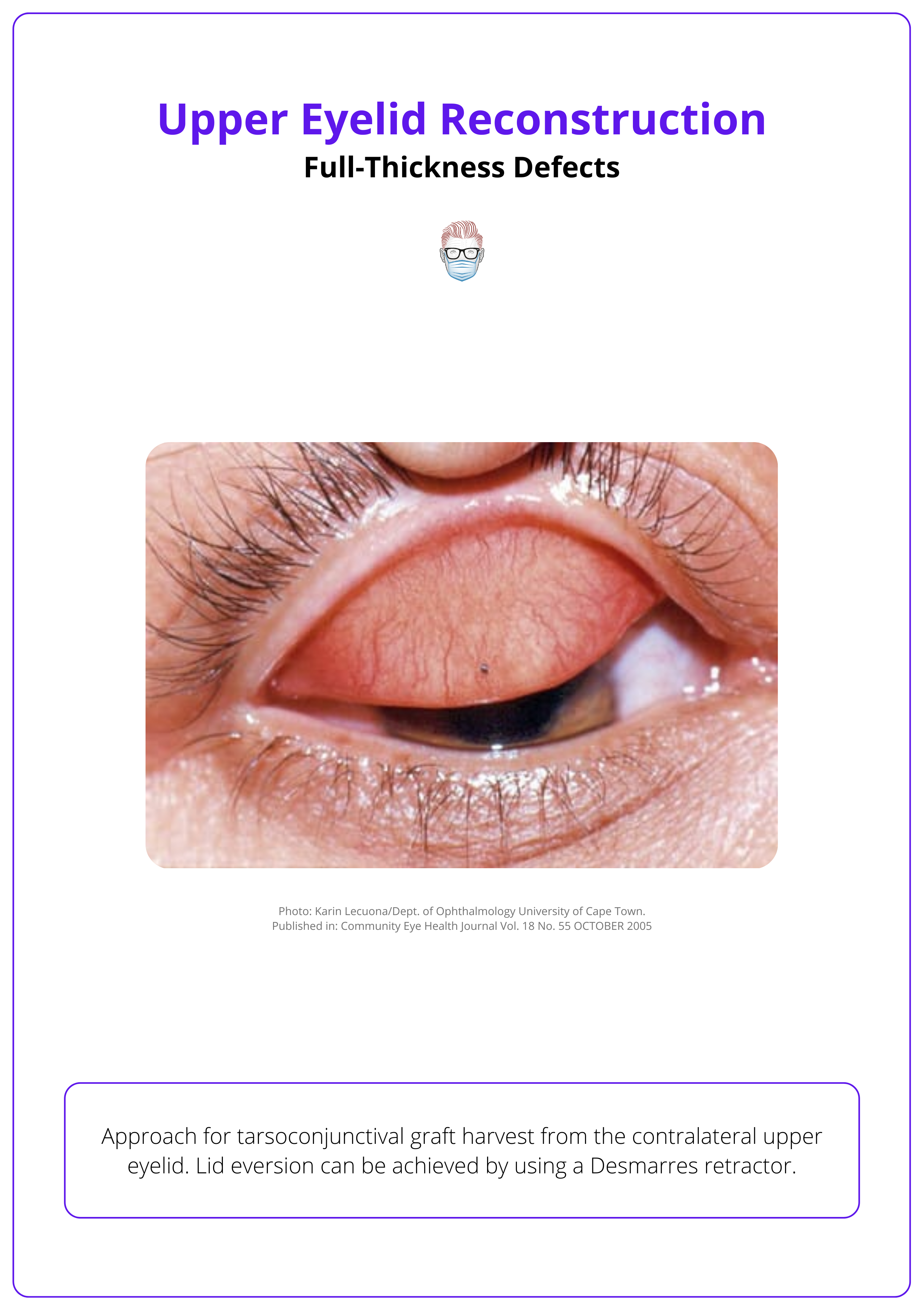

- Tarsoconjunctival Graft:

Harvested from the ipsilateral lower eyelid or contralateral upper eyelid, this graft is ideal for smaller defects, preserving donor eyelid integrity while providing an excellent tissue match. - Chondral Graft:

For smaller defects, the nasal septum is preferred due to limited harvestable tissue. For greater support, auricular cartilage from the conchal bowl provides rigid structural reinforcement (Verity, 2004). - Mucosal Grafts:

These grafts reconstruct the conjunctiva, ensuring a smooth gliding surface to prevent corneal irritation. Donor sites include buccal mucosa, nasal mucosa (often harvested with the nasal septum as a composite graft), and hard palate mucosa for larger defects (Verity, 2004).

Below is a clinical image of the everted upper eyelid.

When reconstructing the posterior lamella, precisely harvest a tarsoconjunctival graft sized to the defect — include a 2 mm superior conjunctival margin to recreate the eyelid edge, avoid oversizing, and select a donor site that matches well.

Complications of Upper Eyelid Reconstruction

Complications can affect both functional and aesthetic outcomes, requiring additional interventions. These can be broadly classified into early and late complications.

Complications following upper eyelid reconstruction can be broadly categorized into early and late issues, each of which may compromise function and aesthetics if not promptly addressed.

Early Complications

- Retrobulbar Hematoma: Severe pain, swelling, and decreased vision requiring urgent decompression and cantholysis to prevent permanent visual impairment.

- Flap/Graft Failure: Partial or complete necrosis due to insufficient vascular supply, hematoma, or infection (Morley, 2010); meticulous surgical technique, proper vascularization, and tension-free closure with close monitoring are essential.

- Infection: Occurring at the graft or donor site; early detection with prompt antibiotic therapy is crucial.

- Corneal Injury: Abrasion or ulceration from exposure or improper eyelid closure (Verity, 2004); using corneal lubricants and temporary protective measures like tarsorrhaphy can minimize damage.

- Eyelid Edema: Temporary swelling that may impair function; typically resolves with supportive care and anti-inflammatory measures.

Late Complications

- Lagophthalmos: Incomplete eyelid closure leading to exposure keratopathy and dry eye (Dhar, 2016); careful initial alignment may prevent this, though revision surgery might be necessary.

- Eyelid Malposition (Ectropion/Entropion): Outward or inward turning of the eyelid causing irritation (Suryadevara, 2009); precise reconstruction of the tarsus and canthal tendons is key, with surgical correction often required.

- Lid Retraction: Incomplete lid lowering from scar contracture or misalignment (Codner, 2010); proper tissue alignment and tension management are vital, with revision surgery as needed.

- Cosmetic Deformities: Poor contour, asymmetry, or scarring that may require secondary procedures such as scar revision or flap debulking (Verity, 2004); meticulous technique can minimize these issues.

- Donor Site Morbidity: Scarring or functional impairment at donor sites (e.g., lower eyelid or forehead); careful planning, surgical technique, and postoperative care help reduce complications.

- Tumor Recurrence: In oncologic cases, inadequate clearance can lead to recurrence (Jennings, 2020); achieving clear surgical margins and vigilant postoperative surveillance are essential.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Upper eyelid reconstruction restores function and aesthetics following defects caused by trauma, tumors, burns, or congenital anomalies.

2. Anatomy & Principles: The upper eyelid consists of anterior, middle, and posterior lamellae. Reconstruction must restore these layers while ensuring corneal protection, tension-free closure, and aesthetic symmetry.

3. Reconstructive Techniques: Partial-thickness defects <25% can be closed directly or with full-thickness skin grafts, while larger defects may require local flaps. Full-thickness defects <25% can be repaired in layers, whereas larger defects need advanced techniques. Total eyelid loss may require brow-based flaps or free tissue transfer.

4. Complications: Risks include lagophthalmos, ectropion, flap necrosis, corneal exposure, and donor site morbidity. Preventative measures include reinforcing canthal tendons, optimizing flap vascularity, and ensuring proper corneal protection postoperatively.

Further Reading

- Codner, M. A., McCord, C. D., Mejia, J. D., & Lalonde, D. (2010). Upper and Lower Eyelid Reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 126(3), 231e–243e.

- Dhar, S. I., Kopp, R., & Tatum, S. A. (2016). Advances in Eyelid Reconstruction. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 24(4), 352–358.

- Janis, J. E. (2022). Essentials of Plastic Surgery: Third Edition. Thieme Medical Publishers.

- Harmon, Christopher B., and Stanislav N. Tolkachjov. Mohs Micrographic Surgery: From Layers to Reconstruction. Thieme, 2023.

- Jennings, E., Krakauer, M., Nunery, W. R., & Aakalu, V. K. (2020). Advancements in the Repair of Large Upper Eyelid Defects: A 10-Year Review. Orbit.

- Morley, A. M. S., deSousa, J.-L., Selva, D., & Malhotra, R. (2010). Techniques of Upper Eyelid Reconstruction. Survey of Ophthalmology, 55(3), 256–271.

- Suryadevara, A. C., & Moe, K. S. (2009). Reconstruction of Eyelid Defects. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America, 17(4), 419–428.

- Verity, D. H., & Collin, J. R. O. (2004). Eyelid Reconstruction: The State of the Art. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 12(5), 344–348.