Summary Card

Overview

Soft tissue sarcomas are malignant tumors of mesenchymal origin, affecting soft tissues such as muscles, fat, and connective tissues.

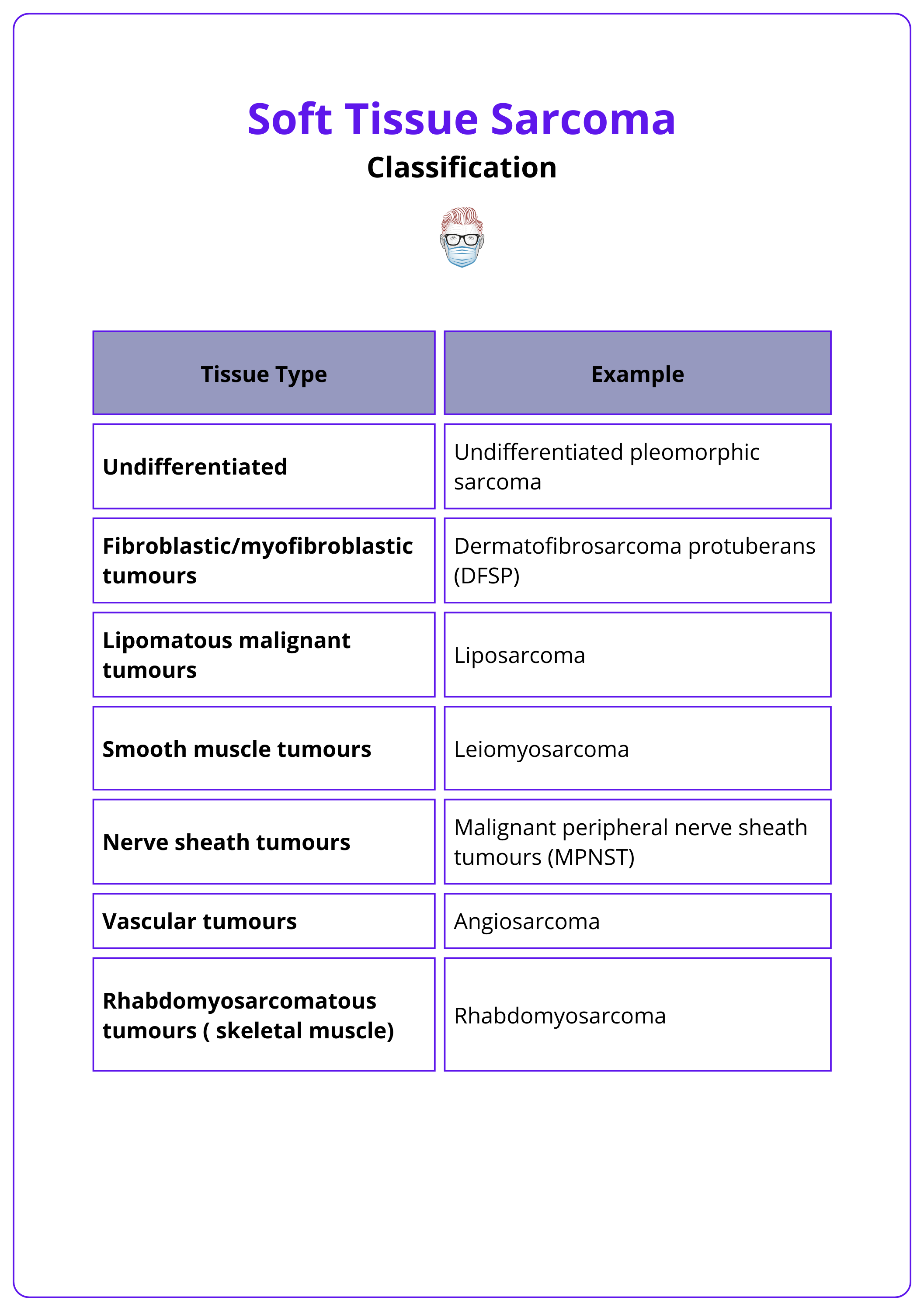

Classification

The WHO classifies soft tissue sarcomas into over 70 subtypes based on tissue origin, using immunohistochemical markers to guide treatment and predict outcomes.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for soft tissue sarcomas include environmental and chemical exposures, radiation, genetic predispositions like Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and chronic lymphedema leading to angiosarcoma.

Clinical Features

Slow-growing, painless mass; physical examination shows a palpable, encapsulated mass, with the assessment of fascial involvement and lymph nodes being critical for prognosis.

Diagnosis

The evaluation of suspected soft tissue sarcomas involves specialised imaging, biopsy techniques, rigorous pathological assessment per 2020 WHO guidelines, and staging via the AJCC system.

Management

Management of soft tissue sarcomas involves surgical excision, radiotherapy to reduce recurrence, and selective use of chemotherapy for high-grade or aggressive tumours.

Specific Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans are among the commonest soft tissue sarcomas seen in clinical practice.

Primary Contributor: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow.

Reviewer: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow.

Overview of Sarcomas

Soft tissue sarcomas are malignant tumors of mesenchymal origin, affecting soft tissues such as muscles, fat, and connective tissues.

Sarcomas are a diverse group of rare, malignant solid tumours originating from mesenchymal tissues. They account for about 1% of adult malignancies and 15% of pediatric malignancies (Gilbert, 2009).

Sarcomas are categorized into two main types.

- Soft Tissue Sarcomas: These affect fat, muscle, nerve tissues, blood vessels, and other connective tissues.

- Malignant Bone Tumors: Examples include osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma.

The lungs are the most common site for metastatic deposits in soft tissue sarcomas. Among adults, the most common soft tissue sarcoma is undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS), while rhabdomyosarcoma is the most frequent subtype in children (Gilbert, 2009).

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS), formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), is now thought to originate from mesenchymal stem cells rather than histiocytes.

Classification of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

The WHO classifies soft tissue sarcomas into over 70 subtypes based on tissue origin, using immunohistochemical markers to guide treatment and predict outcomes.

Soft tissue sarcomas are classified according to their tissue of origin. The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes these tumors into more than 70 subtypes (Sbaraglia, 2020).

Diagnosis of these subtypes relies on specific immunohistochemical markers, typically including keratins, S100 protein and/or SOX10, smooth muscle actin (SMA), and desmin.

Key categories include:

- Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma

- Fibroblastic/Myofibroblastic Tumors: Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans (DFSP)

- Lipomatous Malignant Tumors: Liposarcoma

- Smooth Muscle Tumors: Leiomyosarcoma

- Nerve Sheath Tumors: Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNST)

- Vascular Tumors: Angiosarcoma

- Rhabdomyosarcomatous Tumors: Rhabdomyosarcoma

The classification of soft tissue sarcomas is illustrated in the table below.

Lymph node metastasis occurs in about 5% of cases, with certain subtypes more prone to lymphatic spread, remembered by the acronym "RACES": Rhabdomyosarcoma, Angiosarcoma, Clear cell sarcoma, Epithelioid sarcoma, and Synovial sarcoma (Sinha, 2010).

Risk factors of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Risk factors for soft tissue sarcomas include environmental exposures (e.g., chemicals like herbicides and radiation), genetic predispositions (e.g., Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Neurofibromatosis type 1), and chronic lymphedema.

Several factors have been identified as potentially increasing the risk of developing soft tissue sarcomas (Brennan, 2014).

- Environmental Exposure

- Chemicals, such as herbicides, dioxin, and chlorophenols.

- Radiation, either through medical diagnostics or environmental sources.

- Genetic Predisposition

- Inherited syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Neurofibromatosis type 1, and Gardner's syndrome are associated with an increased risk of soft tissue sarcomas.

- Chronic Lymphedema

- Predisposes to angiosarcoma, as seen in conditions like Stewart-Treves syndrome.

Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma in chronic lymphedema, mainly associated with post-mastectomy but can also occur in primary or chronic lymphedema. (Pereira, 2015).

Clinical Features of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

History often reveals a rapidly growing, painful mass; physical examination shows a palpable, firm mass, with the assessment of fascial involvement and lymph nodes being critical for prognosis.

The onset of symptoms in soft tissue sarcoma (STS) varies with the affected tissue and anatomic site. However, there are key features common that strongly suggest a diagnosis (Misra, 2009). The presence of more cardinal signs increases the risk of malignancy; when all four signs are present, the likelihood of STS is 86% (Johnson, 2001):

- Size > 5cm

- Deep to fascia

- Associated pain

- Increase in size

- Any recurrence of a previously excised lump should also raise the possibility of malignancy.

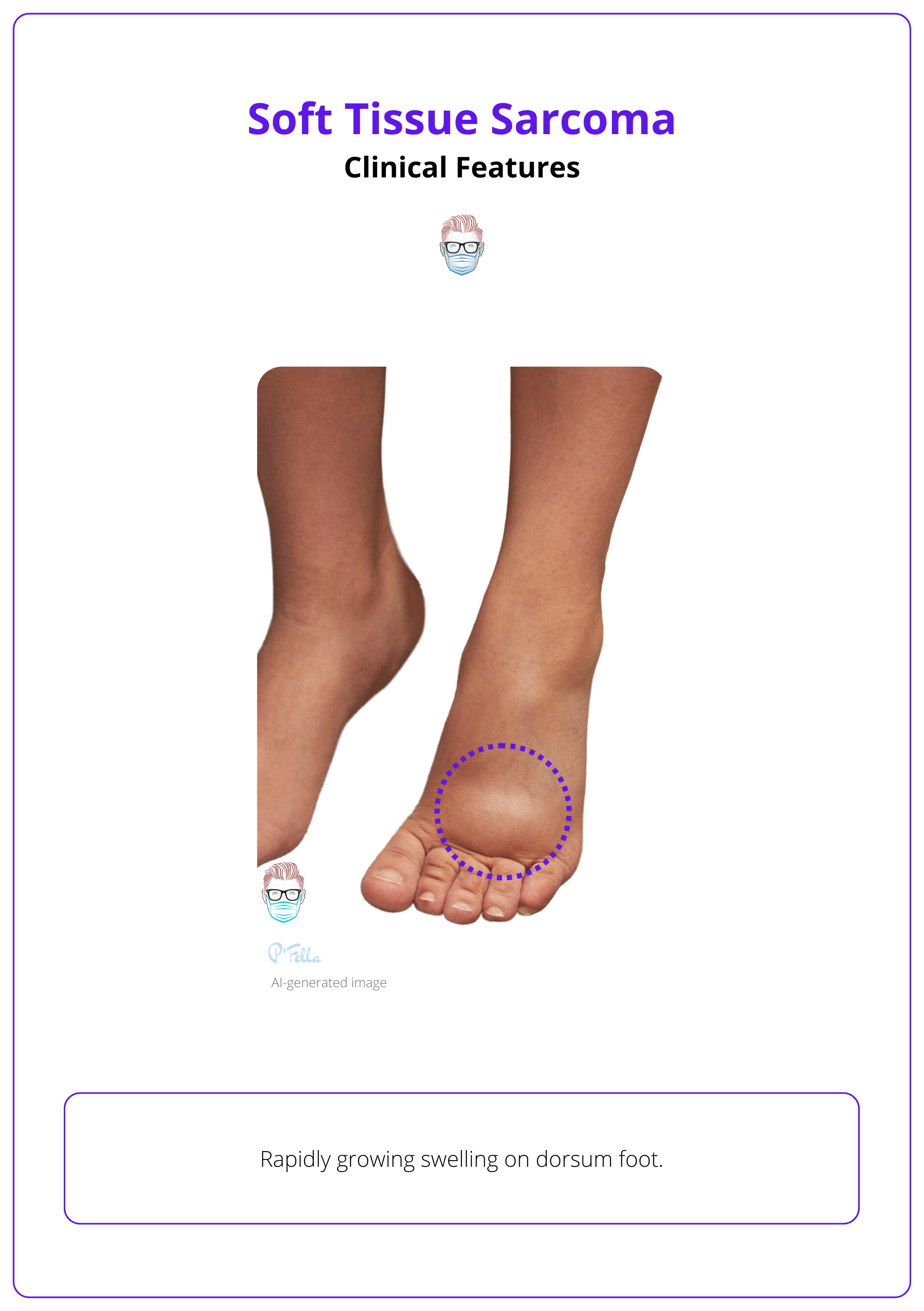

The image below illustrates a rapidly growing soft tissue sarcoma on the foot.

It is important to determine whether the mass is separate from or involves the underlying fascia, as fascial involvement is a poor prognostic indicator. The absence of ecchymosis/bruising suggests an encapsulated mass. Assessment of local lymph nodes is crucial.

History of trauma can sometimes highlight the pre-existing presence of a mass.

Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

In suspected soft tissue sarcomas, a multidisciplinary diagnosis using MRI, CT, and targeted biopsies, aligned with WHO classifications and molecular assessments, optimizes treatment planning and staging.

In cases of suspected soft tissue sarcomas, a detailed and multidisciplinary approach is crucial to ensure accuracy and optimal treatment planning

Biopsy Techniques

- Core Needle Biopsy: standard diagnostic approach, using ≥14-16G needles.

- Excisional Biopsy: Suitable for superficial lesions smaller than 3 cm.

- Open Biopsy: Not recommended except in specialized centers for specific cases.

- Fine Needle Aspiration: Usually insufficient for diagnosis and not recommended.

Pathological and Molecular Assessment

- Diagnosis: Align with 2020 WHO Classification for soft tissue & bone tumors.

- Molecular Diagnostics: complement morphology & immunohistochemistry.

- Grading: FNCLCC system, categorizing tumors based on differentiation, necrosis, and mitotic rate.

- Mitotic Rate: Should be independently reported when possible.

Imaging

- MRI: rimary imaging modality for tumors in the extremities, pelvis, and trunk.

- CT: Important for assessing calcified lesions, pleuropulmonary, and retroperitoneal sarcomas, with comparable effectiveness to MRI.

- Ultrasound: May serve as initial imaging but should lead to CT or MRI if soft tissue sarcoma is suspected.

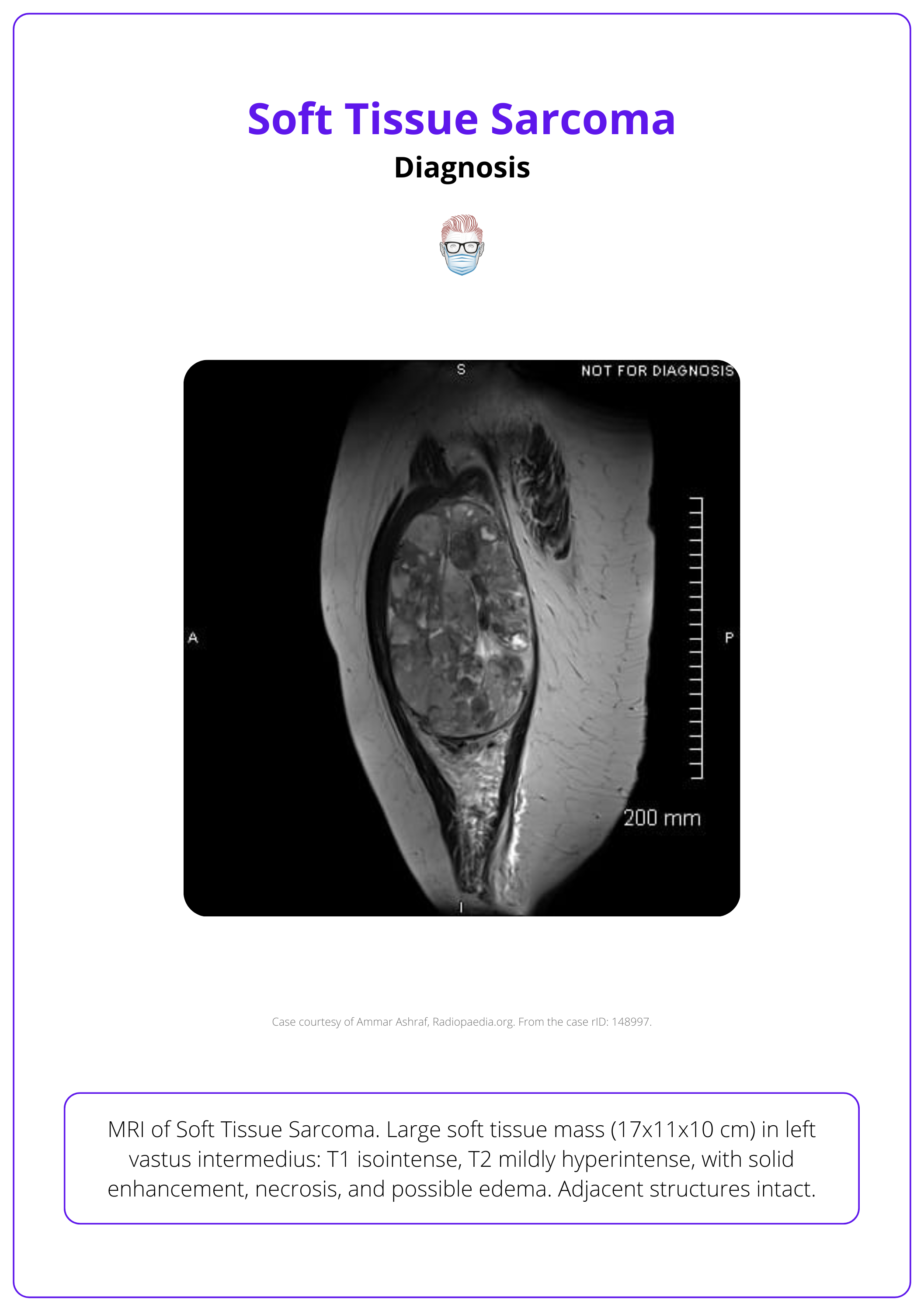

The image below illustrates an MRI image of a soft tissue sarcoma.

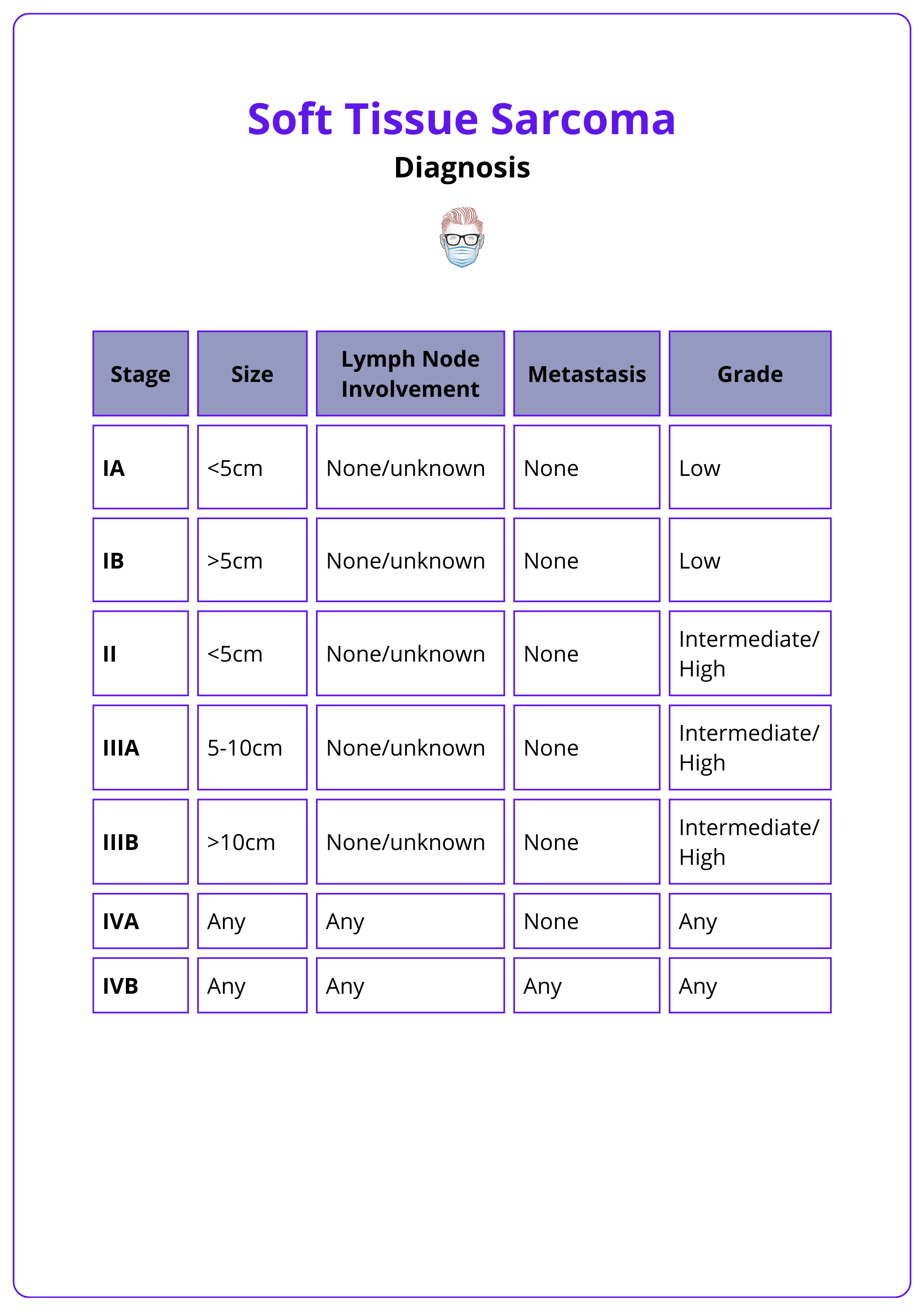

In cases of confirmed diagnosis, the AJCC system is used for staging (Tanaka, 2019). This staging system is summarised in the table below.

When planning a biopsy for suspected soft tissue sarcoma, ensure the tract and scar can be removed in future surgery. Consider tattooing the entry point for accuracy.

Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Soft tissue sarcoma management involves surgery and radiotherapy for local control, with chemotherapy added for high-risk cases, depending on the specific subtype.

Surgery

Surgery is the primary treatment for soft tissue sarcomas, with the approach tailored to the tumor's location, size, and patient comorbidities. The Enneking classification outlines four types of surgical margins (Misra, 2009).

- Wide Local Excision: The tumor and its reactive zone are removed within the same anatomical compartment, through normal tissue. The standard approach for most STS aims for complete resection while preserving limb function. The local Recurrence Rate is 10%.

- Intra-lesional Excision: The excision margin passes through the tumor, leaving residual tumor tissue. Local Recurrence Rate: 80-100%. Indicated primarily for palliative cases due to high recurrence risk.

- Marginal Excision: The surgical plane includes the tumor’s pseudocapsule and reactive zone, often resulting in higher recurrence. Local Recurrence Rate is 40-60%

- Radical Excision: Entire tumor and surrounding compartments are removed. Local Recurrence Rate is 0.5%. Rarely performed if limb salvage is possible; amputation may be necessary for extensive involvement of critical structures.

There are specific surgical considerations in sarcoma surgery:

- En-bloc Removal: Needed for tumors encasing critical structures.

- Close Margins: Acceptable near critical structures without compromising outcomes.

- Prophylactic Nailing: Advised if periosteal stripping >10 cm to prevent fractures.

- Contaminated Tissues: Excise biopsy sites and drain tracts en bloc with the tumor.

- Tissue Resistance: Muscle requires wider margins (2-3 cm); fascia/periosteum provide adequate margins if intact; preserve uninvolved vessels and nerves.

This structured approach to surgical margins helps optimize outcomes while balancing the goals of oncologic safety and limb preservation.

Live Soft Tissue Sarcoma Surgery

Limb Salvage Surgery

Limb salvage surgery (LSS) provides acceptable local recurrence rates using wide excision and radiotherapy, comparable to those of amputation or radical excision. Since amputation does not significantly improve survival outcomes, limb preservation is often preferred to enhance the patient's postoperative quality of life (Misra, 2009).

Some important data includes:

- LSS can be achieved in approximately 90-95% of soft tissue sarcoma cases.

- Recurrence rates for LSS vary between 9% and 22%, with rates higher than this considered unacceptable.

- Amputation: when negative margins can't be achieved, resection risks major nerve damage, or patient comorbidities limit recovery from limb-sparing surgery

Surgery is not first line for synovial sarcoma, which typically requires chemotherapy.

(Neo)Adjuvant Therapies

Radiotherapy:

- Purpose: Enhances local control and facilitates limb-salvage surgery, particularly when clear surgical margins are difficult to achieve.

- Benefits: Preserves critical structures while maintaining low recurrence rates.

- Standard Dosage: Doses over 60 Gy are generally recommended for maximum benefit.

- Techniques:

- External-Beam Radiation Therapy: Commonly used after wide surgical excision for improved outcomes.

- Brachytherapy: Used in some centers, offering similar local control as external-beam radiation.

- Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT): Targets the tumor precisely, minimizing damage to surrounding tissues and reducing complications like wound breakdown and fractures.

Chemotherapy:

- Purpose: Aims to improve survival rates in high-risk STS patients with poor 5-year survival (50-60%).

- Use Cases: Routine in treating rhabdomyosarcomas and soft tissue Ewing’s sarcomas, especially in younger patients.

- Effectiveness: Limited evidence for survival benefits in adult STS, but chemotherapy can reduce the risk of local recurrence and metastasis.

- Recent Advances: Studies show that adjuvant chemotherapy with drugs like doxorubicin and ifosfamide may delay metastatic disease onset in high-risk adult STS patients.

Follow-Up

No standardized follow-up schedule exists, but regular clinical reviews are essential to monitor for local recurrence and metastatic disease. Some hospitals may consider this as their follow-up routine.

- Every 3 months for the first 2 years, including a chest X-ray.

- Every 6 months for the next 3 years.

Monitoring continues for up to 5 years for high-grade tumors and may be longer for low-grade tumors.

The risk of metastasis is highest in the first 2 years.

Specific Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans are among the most common soft tissue sarcomas encountered in clinical practice.

Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma (UPS)

UPS is one of the most aggressive types of soft tissue sarcomas, primarily affecting patients over 60 years of age, with a slightly higher incidence in men (Robles-Tenorio, 2021).

Common types and their typical locations include,

- Deep Soft Tissue UPS: Frequently occurs in the deep soft tissues of the limbs, especially the thigh. Often found in muscle tissue and can grow large before detection.

- Retroperitoneal UPS: These tumors are often very large and may affect multiple organs due to their location.

- Subcutaneous UPS: Found just under the skin; less common and typically smaller with a better prognosis.

- Visceral UPS: Very rare, affecting internal organs like the liver, kidneys, and spleen, making diagnosis and treatment challenging.

Clinical Assessment

- Typically presents as a painless, enlarging mass in the deep soft tissues of the extremities or retroperitoneum.

- MRI is used to assess the extent of the tumor and its relation to adjacent structures.

- Definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy, preferably a core needle biopsy.

Management

- Treatment is primarily surgical, aiming for wide local excision with negative margins.

- Radiotherapy is often employed either preoperatively or postoperatively to reduce recurrence rates.

- Chemotherapy is reserved for advanced or metastatic disease.

- Reconstructive procedures are usually required following extensive resection in cases affecting the extremities.

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans (DFSP)

DFSP is a rare, slow-growing skin cancer known for its aggressive local spread. Key types include,

- Giant Cell Fibroblastoma: Juvenile form, seen in children.

- Myxoid DFSP: Gelatinous due to mucoid substance.

- Pigmented DFSP (Bednar Tumor): Contains melanin, giving a darker appearance.

- Fibrosarcomatous DFSP (FS-DFSP): More aggressive, with higher recurrence and metastatic potential.

- Classic DFSP: The most common, presenting as a slowly enlarging plaque or nodule.

Clinical Assessment

- DFSP presents as a slow-growing, firm dermal nodule that can become plaque-like, often resembling a benign skin condition. It tends to infiltrate deeply into surrounding tissues, including muscle and bone.

- Diagnosis is confirmed through biopsy, with MRI used to define the subcutaneous extent of the disease.

Management

- The primary treatment is surgical, involving wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

- Imatinib may be used for unresectable or metastatic cases, particularly those expressing the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR).

Rhabdomyosarcoma in Children

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most prevalent soft tissue sarcoma in children, with a peak incidence in those under 10 years of age. It is the third most common extracranial solid tumor in the pediatric population, following neuroblastoma and Wilm’s tumor (Wexler, 2011).

The main types include:

- Embryonal: Frequently found in the head, neck, genital, or urinary organs; the most common variant.

- Alveolar: Typically appears in the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, genital organs, or anal area.

- Spindle Cell/Sclerosing: Commonly located in the paratesticular area, with subtypes primarily found in infants (trunk area) and a more aggressive form in the head and neck region.

- Pleomorphic: The least common in children, with variable appearance.

Clinical Assessment

- Children typically present with a rapidly enlarging mass, which may be associated with pain or functional impairment depending on its location.

- Imaging studies, including MRI and CT scans, are crucial for assessing the tumor's size and spread. A core biopsy is essential for histological diagnosis.

Management

- Treatment involves a multimodal approach including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. The goal is to achieve complete resection where possible, supplemented by systemic therapy to address micrometastatic disease.

Conclusion

1. Overview of Sarcomas: Discussed the basic understanding of sarcomas, their significance in pediatric and adult oncology, and highlighted the most common types.

2. Classification of Sarcomas: Explained the WHO classification system which categorizes over 70 sarcoma subtypes based on tissue origin, enhancing treatment through immunohistochemical markers.

3. Risk Factors: Identified environmental, genetic, and other risk factors contributing to sarcoma development, emphasizing the need for awareness and preventive measures in at-risk populations.

4. Clinical Presentation: Outlined typical symptoms and physical findings in sarcoma cases, noting the importance of detailed physical examinations.

5. Diagnostic Process: Covered the multidisciplinary diagnostic approach required for sarcomas, including advanced imaging and biopsy techniques aligned with current WHO guidelines.

6. Management Strategies: Discussed the integrated treatment approach involving surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, tailored to sarcoma types and individual patient cases to optimize outcomes.

7. Specific Sarcoma Types: Provided insights into three prevalent sarcoma types — Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma, Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans, and Rhabdomyosarcoma.

Further Reading

- Gilbert, Nathan F., et al. "Soft-tissue sarcoma." JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 17.1 (2009): 40-47.

- Stein-Wexler, Rebecca. "Pediatric soft tissue sarcomas." Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. Vol. 32. No. 5. WB Saunders, 2011.

- Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Dei Tos AP. The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives. Pathologica. 2021 Apr;113(2):70-84. doi: 10.32074/1591-951X-213. Epub 2020 Nov 3. PMID: 33179614; PMCID: PMC8167394.

- Brennan, Murray F., et al. "Lessons learned from the study of 10,000 patients with soft tissue sarcoma." Annals of surgery 260.3 (2014): 416-422

- Pereira, Elisangela Samartin Pegas, et al. "Stewart treves syndrome." Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 90.3 suppl 1 (2015): 229-231.

- Sinha, Shiba, and A. Howard S. Peach. "Diagnosis and management of soft tissue sarcoma." Bmj 341 (2010).

- Tanaka, Kazuhiro, and Toshifumi Ozaki. "New TNM classification (AJCC eighth edition) of bone and soft tissue sarcomas: JCOG Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Study Group." Japanese journal of clinical oncology 49.2 (2019): 103-107.

- Umer, Hafiz Muhammad, et al. "Impact of unplanned excision on prognosis of patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma." Sarcoma 2013.1 (2013): 498604.

- Robles-Tenorio, Arturo, and Guillermo Solis-Ledesma. "Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma." (2021).

- Llombart, Beatriz, et al. "Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update on diagnosis and management." Seminars in diagnostic pathology. Vol. 30. No. 1. WB Saunders, 2013.