In this Article

5 Key Points

1. Definition

A Pressure Sore or Ulcer is a localised soft-tissue injury secondary to pressure and/or shearing forces.

2. Pathophysiology

Pressure sores are caused by prolonged pressures >33mmgHg which result in localised ischaemia and tissue necrosis.

3. Classification

Several classification systems for pressure sores do exist. The most commonly used option is US-NPUAP, which has 4 main grades.

4. Prevention

The best management is prevention. This involves early identification of high-risk patients and optimise accordingly.

5. Management

Many pressure sores can be treated conservatively. Some patients (grade 3 and 4) may require debridement and soft tissue reconstruction.

Definition

A Pressure Sore is a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear1'.

It can also be called a pressure ulcer, bed sore or decubitus ulcer.

Pathophysiology

Intrinsic and extrinsic factors contribute to localised tissue ischaemia.

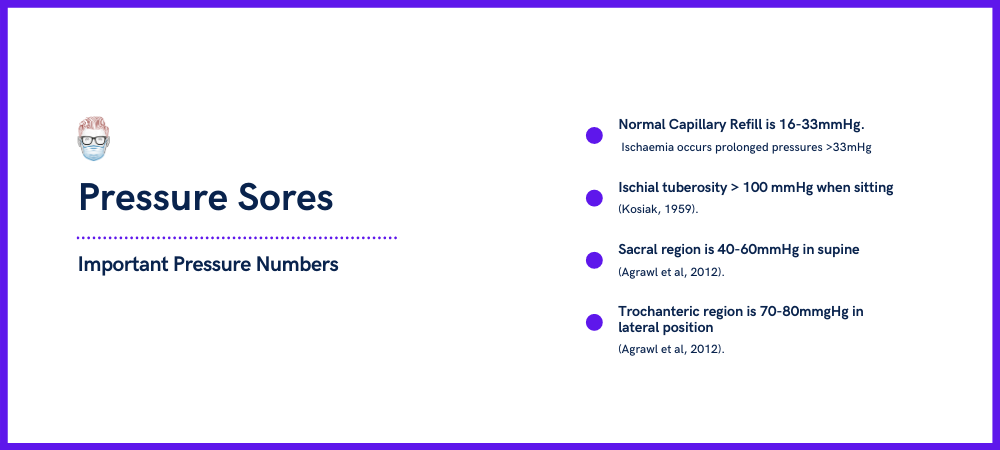

The primary cause of pressure sores is pressure, hence the name. Normal Capillary Refill is 16-33mmHg. Ischaemia can occur at prolonged pressures >33mHg. The amount of pressure applied to one specific area is dependent on the position of the patient. For example:

- Ischial tuberosity > 100 mmHg during sitting (Kosiak, 1959).

- Sacral region is 40-60mmHg in supine (Agrawl et al, 2012).

- Trochanteric region is 70-80mmgHg in lateral position (Agrawl et al, 2012).

Animal models have shown ischemic changes at 2 hours with pressure as low as 70 mmHg and muscle necrosis at 500 mmHg (Daniel, 1985)

Patients who have prolonged pressures at this level often have intrinsic issues, which compound the issue. For example, poor hygiene, reduced protein diet, smoking, medical co-morbidities which decrease perfusion. (Bhattacharya et al 2015). These compounding factors increase immobility, friction, moisture and poorly position the patient. This is discussed further in the next section.

Risk Factors

Any patient with prolonged pressure on specific sites of the body, which can be compounded by medical conditions that result in immoblity, poor hygeine and diet.

Generally speaking, it is often 'common-sense' to predict which patients are high-risk of developing a pressure sore or ulcer. Multiple classification systems to predict this risk have been developed and published.

Common themes in there risk assessment scales include:

- Physical Condition: Activity, Mobility

- Mental State

- Hygiene

- Co-morbidities which increase risk of wound breakdown & decrease risk of wound healing.

Classification

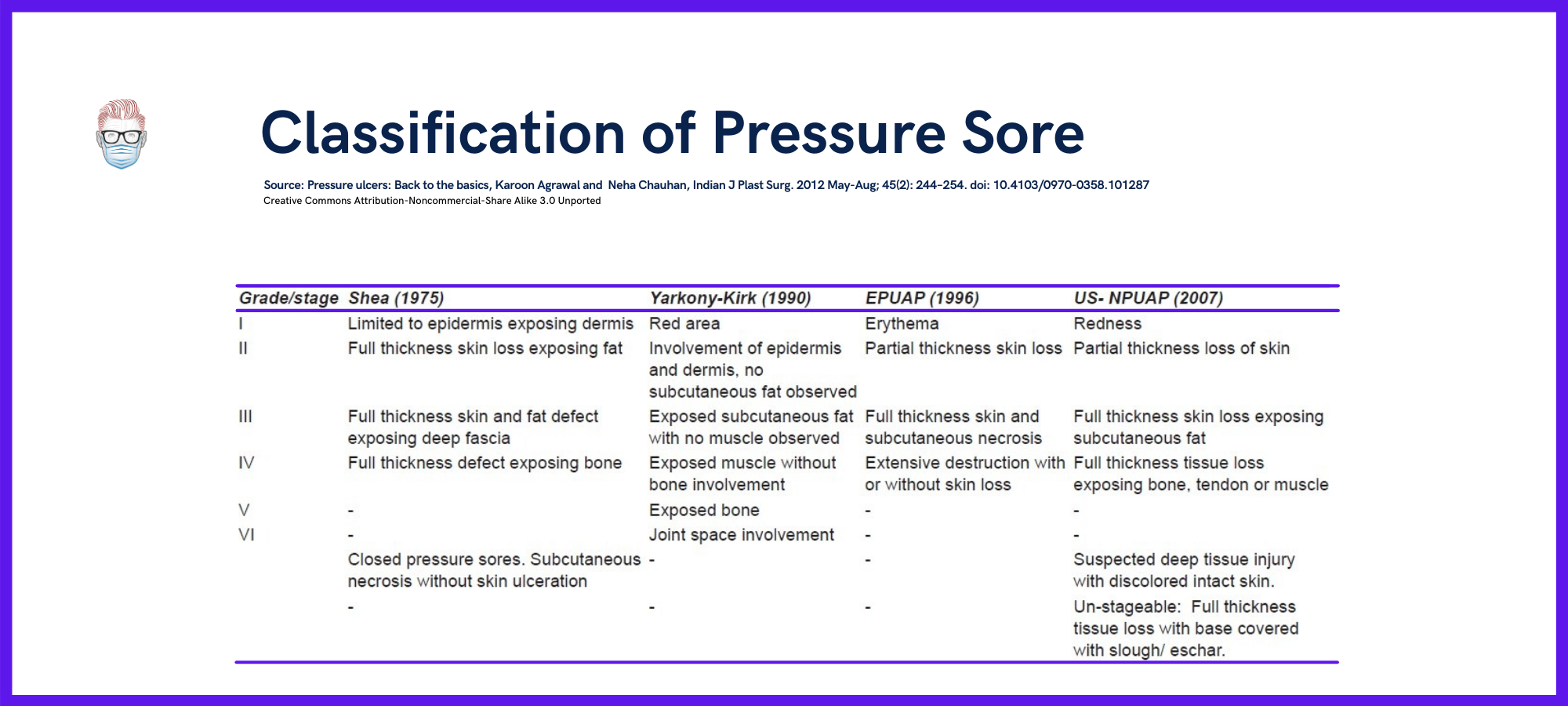

There are several classification systems used in relation to pressure sores/ulcers. The original classification was by O'Shea in in 1975, and now the most commonly used classification system is EPUAP-NPUAP.

These classification systems are suitable for research situations. However they can be difficult to translate into clinical practice becasue they do not take into consideration the patient's current and future condition. Therefore, they can assist but not define clinical decisions for best management. The classification system for pressure ulcers of the skin cannot be used to categorize mucosal pressure ulcers.

Pressure sores most likely occur in areas which receive pressure. These include the sacrum, ilium, ischium, heels, scapula, elbows. This is visualised in the illustration below.

When examining a pressure sore, it's also important to common on sinus tracts, undermining, odor, exudate and periwound condition. Skin is much more pressure-resistant than muscle. This can lead to a “tip of the iceberg” phenomenon, where the skin can mask a much deeper wound (Cushings et al, 2013).

Management of Pressure Sores

Pressure Sores and Ulcers should be managed in a multi-discplinary team of surgeons, medics, nutritionists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists. Each team member working towards a common goals of pressure redistribution, wound stability and patient optimisation.

Summary of Evidence:

- No type of conservative treatment has shown superiority (Reddy et al, 2006).

- No dressings have been proven superior to other dressings (Fan et al, 2011).

- Mixed evidence on types of non-operative debridement (Reddy et al 2008).

- Recurrence rates vary from 2-83% (Cushings et al, 2013).

Prevention

The best management for pressure sores is prevention. This can be done by the following:

- Early identification and optimisation of high risk patients.

- Pressure redistribution with scheduled turning and body repositioning to reducing shearing forces.

- Protection of vulnerable bony prominence using pillows, devices with adequate padding, and specialty beds (air mattresses)

- Skin care and keeping wounds dry and clean.

- Nutritional Supplementaion (Bourdel-Marchasson et al, 2000)

In terms of nutrition, the following are commonly referenced (NUPAP, 2014):

- Energy: 30-35 kcalories/kg body weight for adults

- Protein: 1.25 to 1.5 grams protein/kg body weight daily for adults

- Adequate hydration on a case-by-case basis.

- Albumin Level: goal >2.0g/dl (Lawdig et al, 2002)

- Vitamin C supplementation has mild benefit (Keys et al, 2010)

Non-Operative/Conservative Management

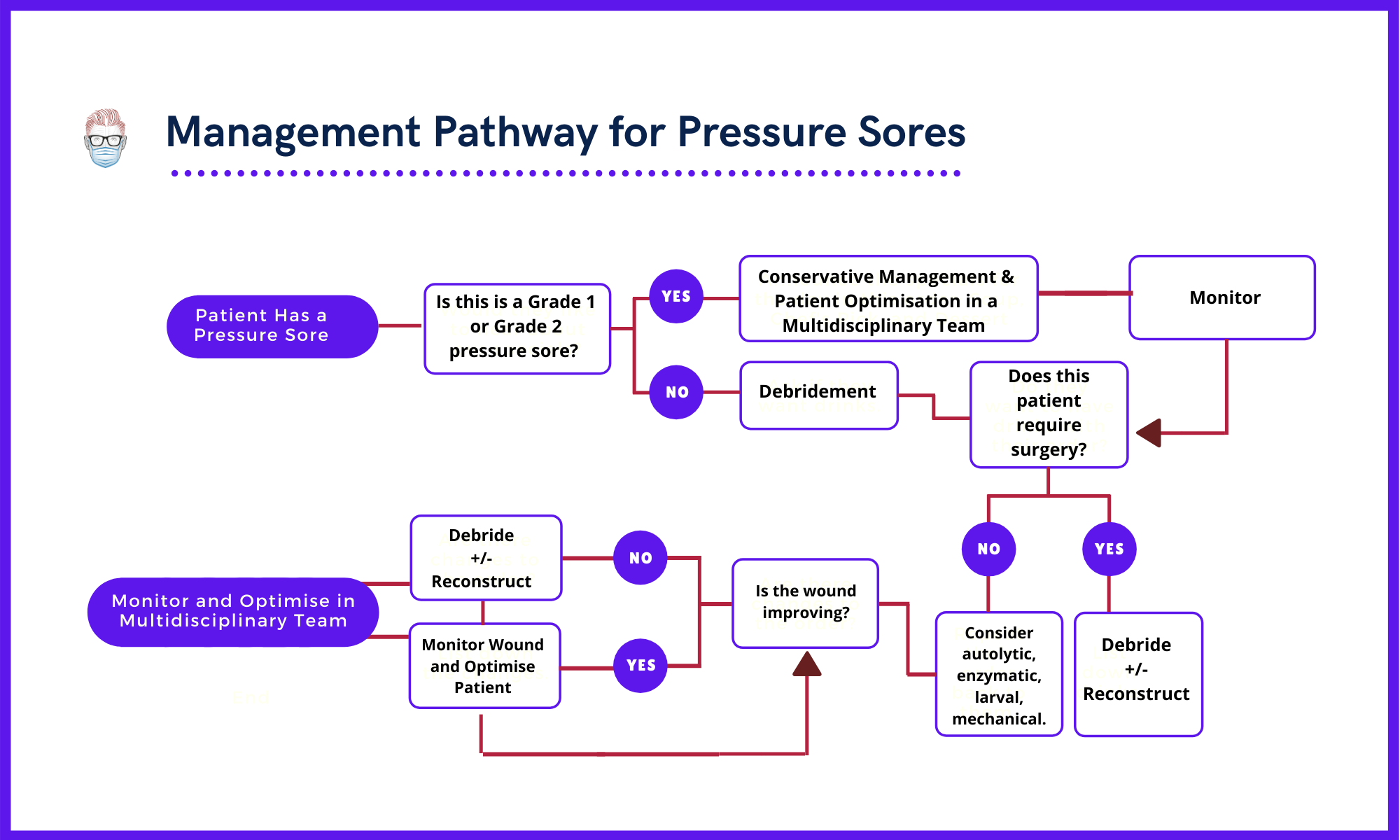

Non-operative management is generally considered for patients who have a stage 1 or 2 ulcer. No conservative treatment option has proved superior to other options (Reddy et al, 2006).

This management is quite similar to preventative management and it involved:

- Pressure Offloading

- Enzymatic Wound debridement

- Wound cover using adequate dressings. No dressings has been proven to be superior than other wound dressings (Fan et al, 2011)

- Antibiotic cover

Non-operative debridement includes autolytic, enzymatic, larval, mechanical. These types should be considered when there is no urgent clinical need for drainage or removal of devitalized tissue. The current evidence for this is mixed (Reddy et al 2008).

Currently no unequivocal evidence for role of hyperbaric therapy (Reddy et al 2008).

Operative Management

Patients with a stage 3 and stage 4 pressure ulcer should be considered for operative management.

Absolute indications for surgical debridement include necrosis, advancing cellulitis, crepitus, fluctuance, and/or sepsis secondary to ulcer-related infection (NUPAP, 2014). There should be a high index of suspicion of biofilm if present >4 weeks and lacks signs of any healing in the previous 2 weeks.

The choice of reconstruction depends on location, size, and depth of the pressure sore. Each choice has benefits and limitations, as discussed below.

- Skin Grafting: often lack sufficient bulk and strength, which results in a high failure rate.

- Fasciocutaneous Flaps: durable, well-vascularised but limited bulk may not be sufficient for deeper wounds. For example, a rotation flap or rhomboid flap.

- Musculocutaneous flaps: provide more depth of coverage, higher bacterial resistance.

- Free Tissue Transfer: This has been described by is less commonly utilised (Whitney et al, 2006).

In these cases, patients may require a bladder and/or bowel diversion.

Emerging Therapies

Microclimate Control

- Control moisture & temperature when selecting a support surface.

- Specialized surfaces can change rate of evaporation and heat dissipation from the skin (2010, Wound International)

- Avoid heat - it increases metabolic rate, induces sweating and decreases the tolerance of the tissue for pressure.

Electrical Stimulation

There is emerging evidence that electrical stimulation (ES) induces intermittent tetanic muscle contractions and reduces the risk of pressure ulcer development in at risk body parts, especially in individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI). (NUPAP, 2014)

Acknowledgements:

Contributing Author: Manal Nasir, Karachi, Pakistan. Final year MBBS

Verified by thePlasticsFella