Summary Card

Definition

Osteomyelitis is inflammation due to infection of the bone by bacteria, mycobacteria, or fungus.

Aetiology

Osteomyelitis can result from haematogenous seeding, direct inoculation, or contiguous spread. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen.

Clinical Features

Osteomyelitis presents with pain and reduced movement. Acute cases show systemic signs of infection, while chronic cases may involve overlying skin changes and drainage through a sinus tract.

Investigations

A diagnosis of suspected osteomyelitis is confirmed by positive bone microbiology samples. MRI and FDG-PET are the most sensitive and specific imaging techniques.

Management

Targeted antibiotic therapy is the first choice for acute osteomyelitis. In subacute and chronic cases, aggressive debridement combined with an orthoplastic approach is required for definitive management.

Primary Contributor: Dr Suzanne Thomson, Educational Fellow.

Reviewer: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow.

Definition of Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis is inflammation due to infection of the bone by bacteria, mycobacteria, or fungus. It is usually secondary to direct inoculation through trauma or local soft tissue infection, but haematogenous spread can occur, particularly in pediatric patients.

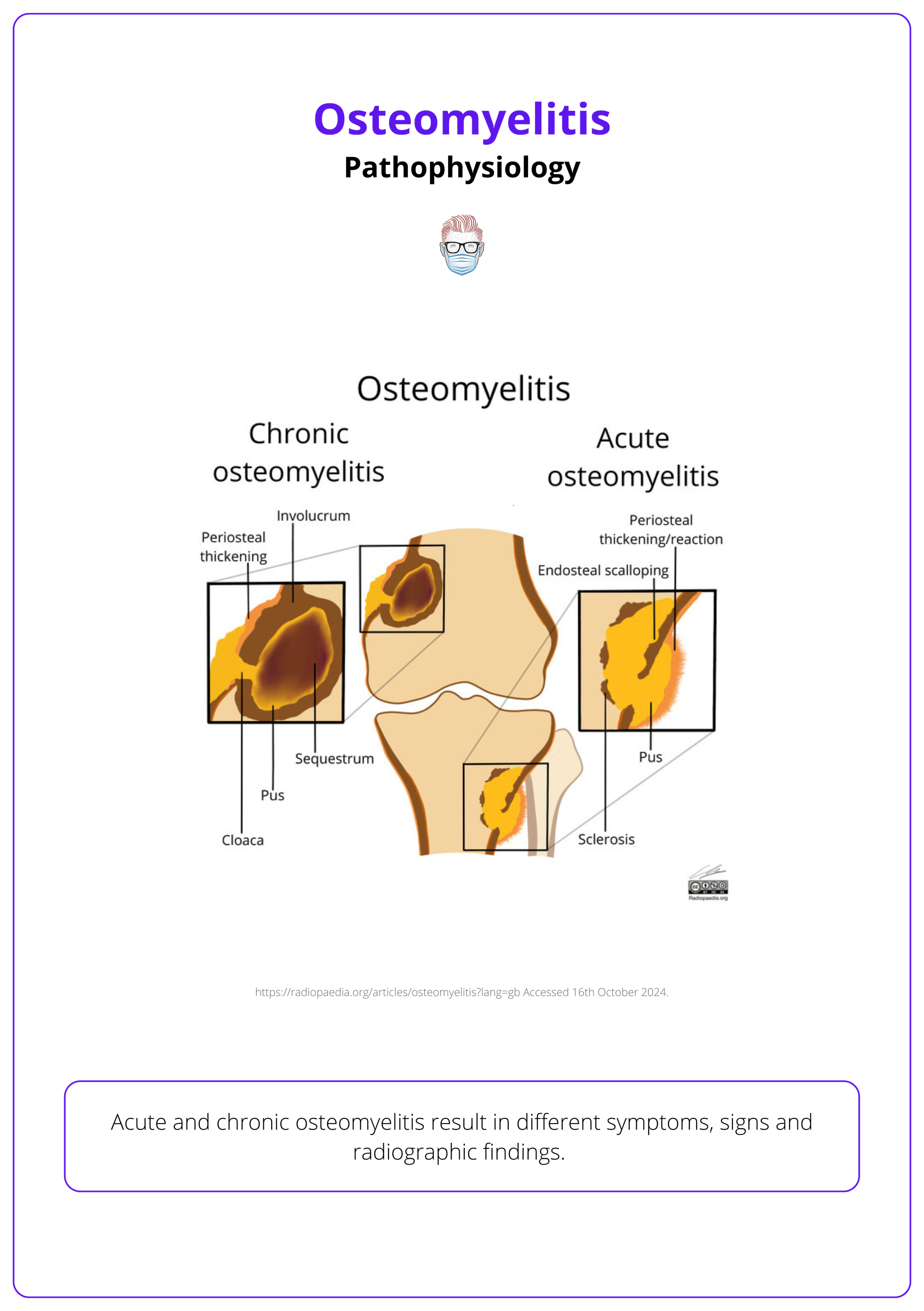

Osteomyelitis is a bone infection commonly caused by direct inoculation, haematagenous or contiguous spread. The infection causes bone tissue death (necrosis) and leads to the formation of dead bone fragments (sequestra). Subperiosteal abscesses may develop, prompting new bone formation (involucrum) as a protective response.

It can be classified as:

- Acute: Within 2 weeks of the initial infection.

- Subacute: Occurs between 2 weeks to several months after the insult.

- Chronic: Manifests several months post-infection.

Aetiology of Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis can result from haematogenous seeding, direct inoculation, or contiguous spread. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen, with risk factors including conditions that impair blood supply.

Types of Pathogens

The most common causative organism of osteomyelitis is Staphylococcus aureus (80% of cases). Other pathogens associated with osteomyelitis include:

- Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp.: Common in IV drug users and those with genitourinary infections.

- Salmonella spp.: Frequently found in patients with sickle cell disease.

- Haemophilus influenzae, Group B streptococci: Common in neonates.

Types of Transmission

These organisms can cause osteomyelitis through 3 mechanisms:

- Haematogenous Spread is a common method in paediatrics due to high bone vascularity. In adults, vertebrae are most commonly affected.

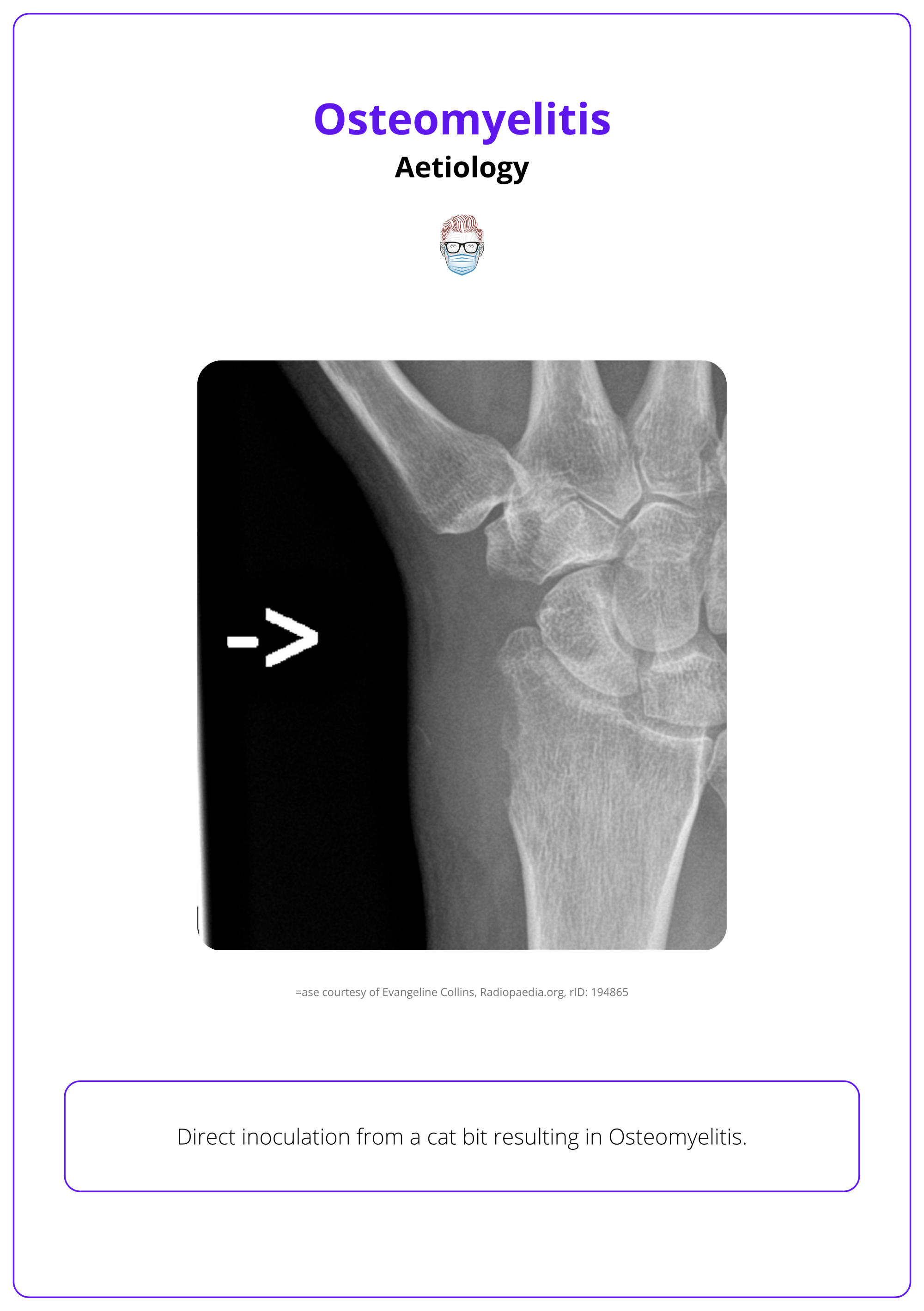

- Direct Inoculation from trauma (e.g., fractures) or surgery. Poor vascularity in the affected area increases susceptibility to infection.

- Contiguous Spread from adjacent soft tissue infections, such as paronychia.

There is a seasonal variation in acute haematogenous osteomyelitis in children, with the majority of cases presenting during the summer months (Lindsay, 2015).

In rare cases, osteomyelitis can occur without bacterial infection, as seen in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO), a non-suppurative inflammatory disorder. (Pinder, 2015)

Clinical Features of Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis presents with distinct acute and chronic symptoms. Acute cases show systemic signs of infection, while chronic cases may involve overlying skin changes and sinus tract.

History

Osteomyelitis is characterised by localized bone pain, typically worsening with movement or weight-bearing. In chronic cases, pain may be persistent but less intense than in acute cases.

There can often be associated systemic symptoms, such as:

- Acute: fever, malaise, and lethargy

- Chronic: fewer systemic signs but could have chronic low-grade fever.

Patient history might identify risk factors such as:

- Vascular Insufficiency: Poor blood flow (e.g., in diabetes or peripheral vascular disease) increases risk.

- Chronic Illnesses: Diabetes, sickle cell disease, and immunosuppression.

- IV Drug Use: Associated with direct bacterial inoculation risk.

A history of recent antibiotic use is important to note, as it can mask classic signs of osteomyelitis, making diagnosis more challenging.

Examination

In osteomyelitis, clinical examination reveals distinct local signs based on the stage of infection, with acute cases displaying inflammatory symptoms and chronic cases showing structural changes and potential drainage

Local Signs

- Acute: Erythema, warmth, and swelling over the affected area, with tenderness on palpation.

- Chronic: skin induration or thickening, a sinus tract allowing for spontaneous discharge of purulent material.

In both types, reduced mobility in nearby joints, especially in chronic cases where pain limits function.

The most common site of bone involvement differs by age:

- Neonates: Metaphysis and epiphysis.

- Children: Metaphysis.

- Adults: Epiphysis and subchondral regions.

Differential Diagnosis

- Septic Arthritis: Presents similarly with pain, warmth, and swelling but is joint-centered rather than bone-centered.

- Cellulitis: May mimic local signs of osteomyelitis but without deep bone involvement.

- Bone Tumors: Particularly in chronic cases, differentiate osteomyelitis from neoplastic causes of localized bone pain.

- Gout/Pseudogout: Acute joint pain and erythema may resemble osteomyelitis but typically show crystal deposits on imaging or aspiration.

Osteomyelitis of the hand is rare, comprising only 1-6% of all hand infections and about 10% of all osteomyelitis cases (Pinder, 2015).

Investigations for Osteomyelitis

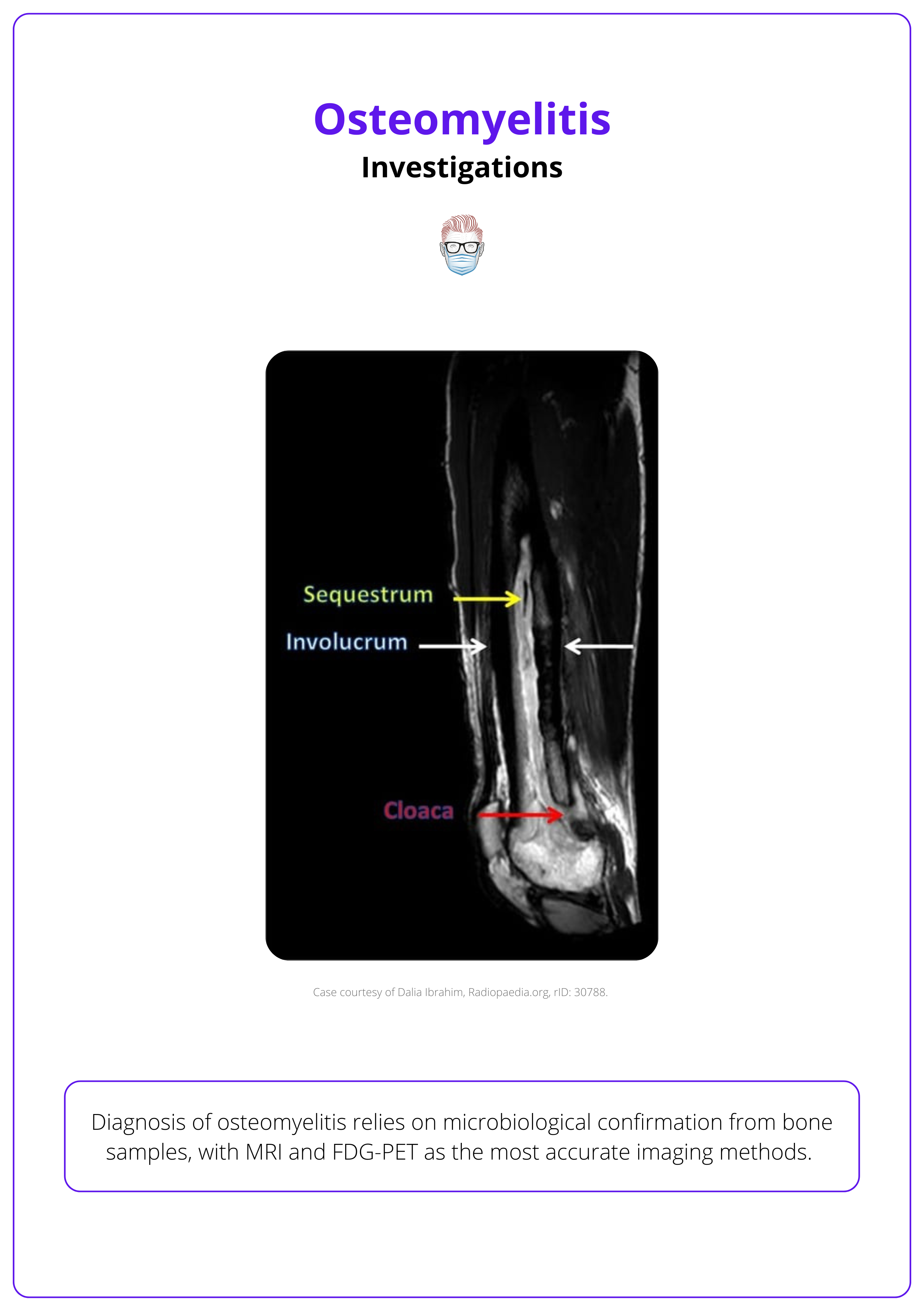

Diagnosis of osteomyelitis relies on microbiological confirmation from bone samples, with MRI and FDG-PET as the most accurate imaging methods. Antibiotics should be withheld until samples are obtained to avoid masking the infection.

Investigating osteomyelitis requires a structured approach involving blood tests, microbiological analysis, and imaging studies. This approach aids in confirming the infection source, identifying causative organisms, and assessing the extent of bone and soft tissue involvement.

Blood Tests

Blood tests provide initial clues and help monitor the inflammatory response, though they are not diagnostic on their own.

- White Cell Count (WCC): Elevated in acute cases, though less reliable in chronic infection.

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Sensitive marker for inflammation, often elevated in osteomyelitis.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): Elevated ESR can suggest chronic inflammation or bone involvement.

Microbiological Diagnosis

Direct microbiological analysis from bone samples is essential for a definitive diagnosis and should be prioritized before starting antibiotics.

- Bone biopsy: Gold standard for microbiological confirmation. Antibiotic therapy should be withheld until samples are collected to avoid interference with pathogen detection.

As stated before, the most common pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus. Other organisms include Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp, Salmonella spp. Haemophilus influenzae, and Group B streptococci.

Radiological Investigations

Imaging is crucial for identifying the extent of bone and soft tissue involvement, with MRI and FDG-PET offering the highest sensitivity and specificity.

MRI is ideal for early detection and assessing soft tissue involvement. Key signs include:

- Bone Marrow Edema: Detectable within 1-2 days of infection onset.

- Brodie’s Abscess: Intraosseous abscess, common in children near growth plates.

- Penumbra Sign: Seen on T1-weighted MRI as an enhancing rim around an intraosseous abscess, further defined with contrast.

The image below illustrates a T1-weighted MRI of osteomyelitis.

FDG-PET: Highly sensitive for detecting infected areas through increased metabolic activity.

Plain X-ray Detects bone changes only after significant mineral loss (≥40%) and infection spread (≥1 cm). Findings include:

- Periosteal Reaction: Formation of Codman’s triangle due to rapid periosteal elevation.

- Endosteal Scalloping and Osteopenia: Indicators of chronic bone involvement.

- Sequestrum and involucrum

Management of Osteomyelitis

Targeted antibiotic therapy is the primary treatment for acute osteomyelitis. For subacute and chronic cases, effective management requires aggressive debridement and an orthoplastic approach, addressing both infection and structural defects.

The management of osteomyelitis depends on the infection’s acuity. Acute osteomyelitis primarily involves antibiotics, while chronic or subacute cases require a combination of surgical debridement and reconstruction to eradicate infection and restore function.

Acute Osteomyelitis

In acute cases without abscess formation or bony sequestrum, antibiotics remain the mainstay.

- Targeted Therapy: Antibiotics should be tailored based on culture results, with initial broad-spectrum coverage adjusted once the causative organism is identified.

- Duration: Typically, a 6-week antibiotic course is required. Collaboration with microbiology helps refine the regimen.

Subacute and Chronic Osteomyelitis

Subacute and chronic osteomyelitis requires a combined approach, addressing both the infection and any associated bone or soft tissue defects.

Surgical Debridement

- Bone Biopsies: Should be taken before starting antibiotics to avoid masking pathogens.

- Pre-operative Imaging: Guides the extent of debridement.

- Debridement Procedure: All infected tissue, abscesses, and necrotic bone must be meticulously removed.

Reconstruction

- Soft Tissue Coverage: Essential to promote healing, prevent recurrence, and enhance antibiotic delivery.

- Tissue Flaps: Local or distant flaps may be used to cover defects, ensuring robust coverage for optimal recovery.

Adjunctive Measures

- Antibiotic-Impregnated Materials: Sutures, spacers, and bone substitutes can assist with localized infection control.

Post-operative Monitoring involves Clinical observation, temperature tracking, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are used to assess recovery and guide the transition to oral antibiotics (Gornitzky, 2020).

Periosteal flaps, known for enhancing blood supply, can be used to support bone healing after debridement in cases of osteomyelitis (Kakar, 2011).

Conclusion

1. Definition of Osteomyelitis: Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bone, typically caused by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and spread through direct inoculation, local soft tissue infection, or, less commonly, haematogenous spread, particularly in children.

2. Epidemiology of Osteomyelitis: The incidence of osteomyelitis is around 8-20 cases per 100,000 annually. It affects males more frequently, with risk factors including diabetes, vascular disease, and IV drug use.

3. Presentation of Osteomyelitis: Acute osteomyelitis presents with localized pain, swelling, fever, and systemic symptoms, while chronic cases involve persistent pain and reduced mobility, sometimes with sinus tract formation and drainage.

4. Investigations for Osteomyelitis: Diagnosis is confirmed by bone biopsy and microbiology. MRI and FDG-PET are the most sensitive imaging techniques, while blood tests reveal elevated CRP, ESR, and WCC.

5. Management of Osteomyelitis: Acute osteomyelitis is treated with targeted antibiotics, while chronic cases require surgical debridement and reconstruction, often using an orthoplastic approach to restore function and prevent recurrence.

Further Reading

- Gornitzky AL, Kim AE, O'Donnell JM, Swarup I. Diagnosis and Management of Osteomyelitis in Children: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2020 Jun;8(6):e1900202. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00202. PMID: 33006465.

- Smith IM, Austin OM, Batchelor AG. The treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a 10 year audit. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(1):11-5. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.07.002. PMID: 16482785.

- Pinder R, Barlow G. Osteomyelitis of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016 May;41(4):431-40. doi: 10.1177/1753193415612373. Epub 2015 Oct 19. PMID: 26482914.

- Foong B, Wong KPL, Jeyanthi CJ, Li J, Lim KBL, Tan NWH. Osteomyelitis in Immunocompromised children and neonates, a case series. BMC Pediatr. 2021 Dec 11;21(1):568. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-03031-1. PMID: 34895166; PMCID: PMC8665553.

- Momodu II, Savaliya V. Osteomyelitis. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532250/

- Lindsay EA, Tareen N, Jo CH, Copley LA. Seasonal Variation and Weather Changes Related to the Occurrence and Severity of Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis in Children. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 May 15;7(2):e16-e23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix085. PMID: 29045692.

- Collins 2024, Radiopedia osteomyelitis, accessed October 2024.

- Gornitzky AL, Kim AE, O'Donnell JM, Swarup I. Diagnosis and Management of Osteomyelitis in Children: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2020 Jun;8(6):e1900202. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00202. PMID: 33006465.

- Kakar S, Duymaz A, Steinmann S, Shin AY, Moran SL. Vascularized medial femoral condyle corticoperiosteal flaps for the treatment of recalcitrant humeral nonunions. Microsurgery. 2011 Feb;31(2):85-92