Summary Card

Definition

Merkel cell carcinoma is a malignant skin lesion arising from neuroendocrine cells.

Risk Factors

Include sun exposure, older age, immunosuppression, being Caucasian, and being male.

Pathogenesis

Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is a recently discovered polyomavirus in MCC tumour tissue.

Clinical Features

A fast-growing, painless, firm, non-tender cutaneous nodule. It is reddish-purple with a shiny surface, most commonly in the head and neck region.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of MCC consists of histopathology with an immunohistochemistry panel. An SNLB should be performed on all patients who are diagnosed with MCC.

Clinical Staging

MCC is classified and staged from the AJCC 8th edition of 2017.

Treatment

Treatment of MCC involves wide local excision +/- radiotherapy as MCC is very radiosensitive. Chemotherapy is rarely used, except occasionally for palliative care.

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow.

Reviewer: Dr Suzanne Thomson, Educational Fellow.

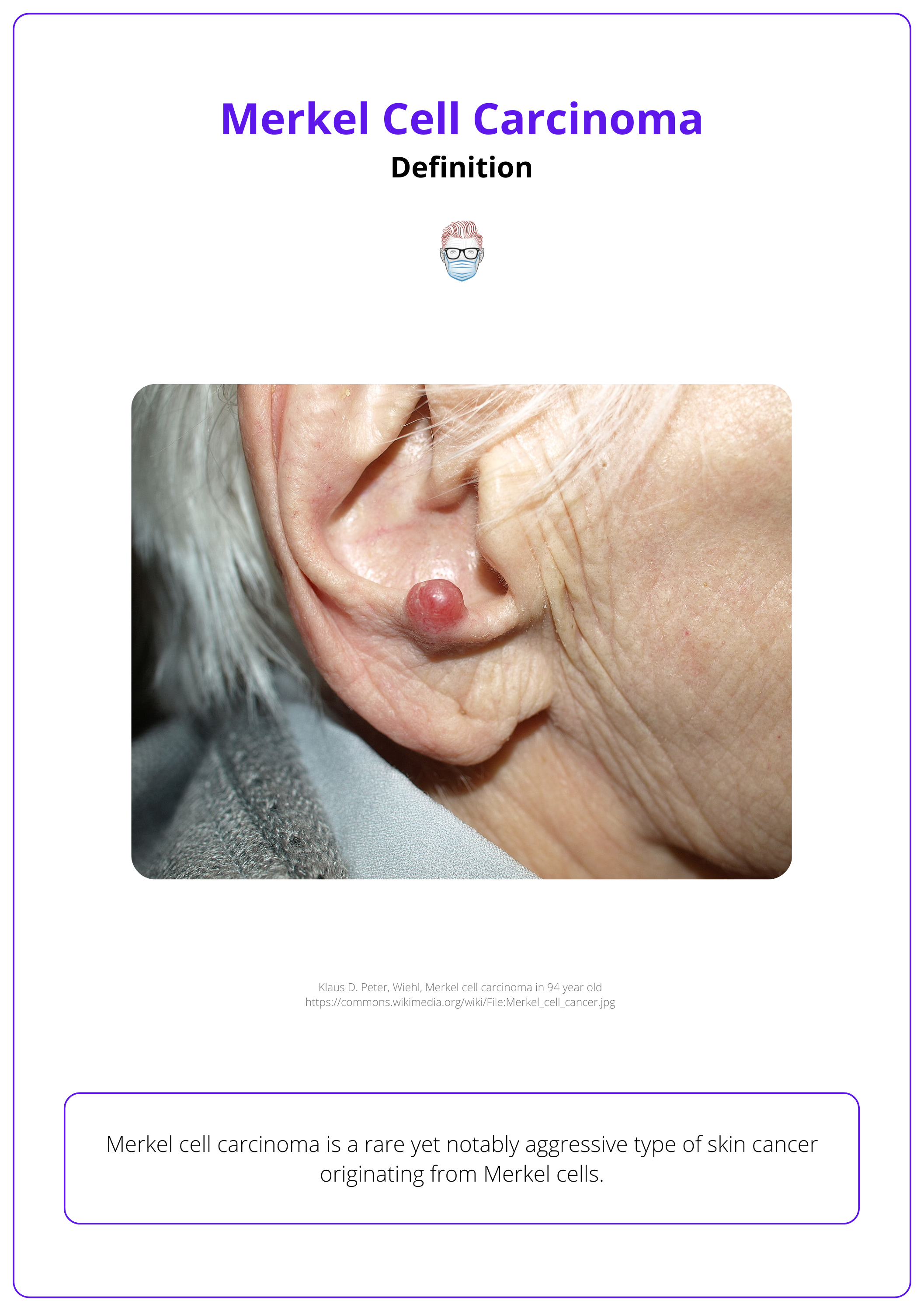

Definition of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare, but aggressive malignant skin lesion arising from neuroendocrine cells.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare but aggressive neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin found at the dermoepidermal junction. It originates from Merkel cells, first identified in 1875 by Friedrich Sigmund Merkel.

Initially thought to be non-keratinizing epidermal cells, Merkel cells are now understood to be primary neural cells located within the basal layer of the epidermis (Goessling, 2002). MCC exhibits features of both epithelial and neuroendocrine origin.

The image below visualizes Merkel cell carcinoma in the ear.

Merkel cells function as mechanoreceptors, essential for the body's touch-sensitivity response (NCI, 2024)

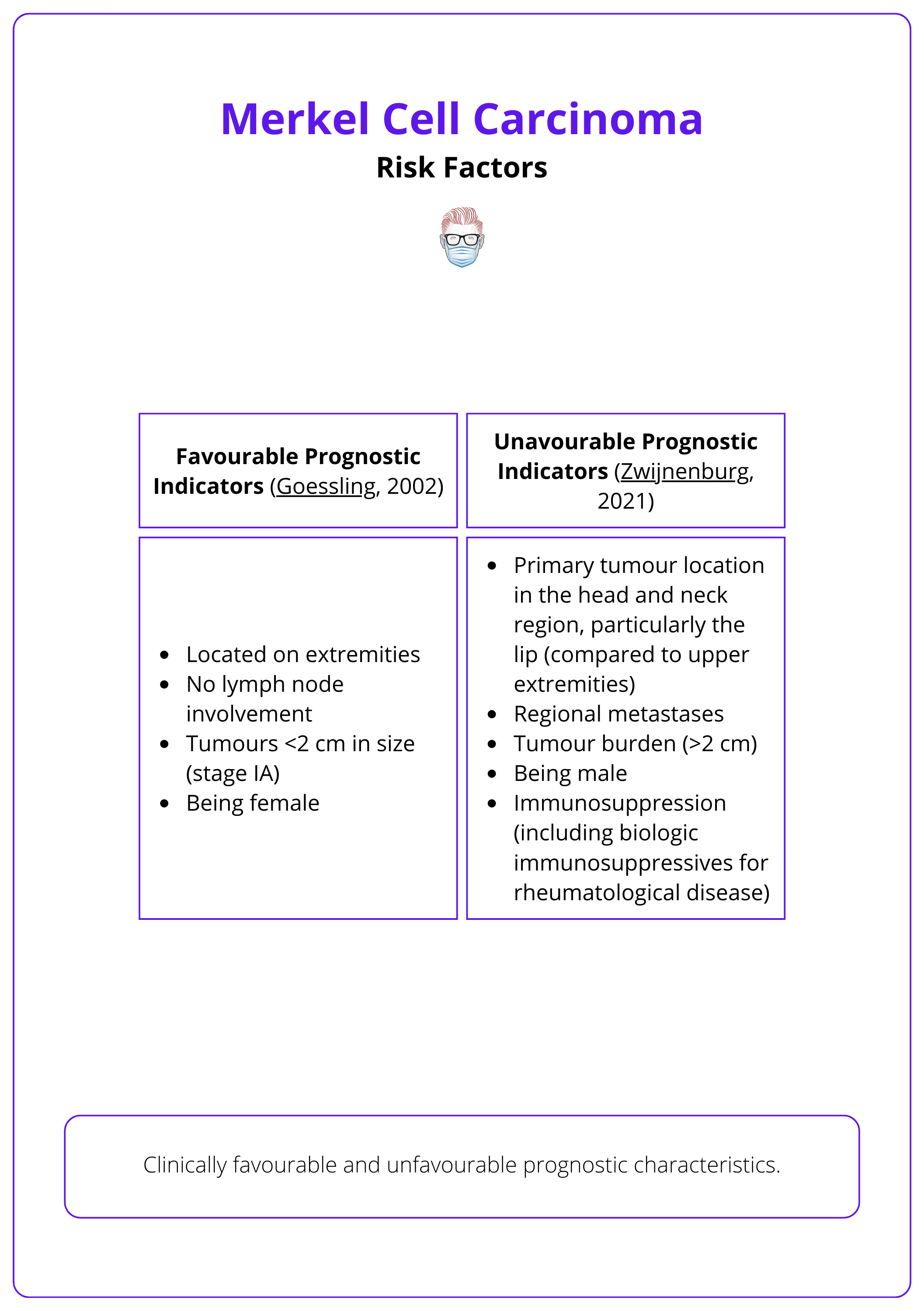

Risk Factors of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Risk factors for MCC include sun exposure, age, immunosuppression, and being caucasian and male.

As the incidence of Merkel cell carcinoma continues to rise globally, understanding the risk factors and epidemiological trends is essential for early detection and prevention. Recognised risk factors include:

- Sun exposure

- Increasing age

- Being Caucasian

- Immunosuppression

- Being male

- Infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV)

For risk factors, consider an elderly Caucasian male who is on immunosuppressive medications and has had extensive sun exposure.

The table below categorizes favourable and unfavourable prognostic indicators of MCC.

More than 70% of patients are over the age of 70 at the time of diagnosis (Zwijnenburg, 2021).

Pathogenesis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

The discovery of the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in MCC tumor tissues has significantly advanced the pathogenesis of Merkel cell carcinoma.

Merkel cell carcinoma can develop through two distinct pathways with similar clinical presentations and prognoses but differing in aetiology. (Dellambra, 2021)

- The integration in the patient DNA of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV).

- Triggered by extensive DNA mutations due to UV radiation and as such MCC most often arise in sun-exposed areas of the body.

Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV)

This is a recently discovered polyomavirus in MCC tumour tissues. The prognostic significance of viral load, antibody titer levels, and the role of underlying immunosuppression in hosts is yet to be determined (NCI, 2024).

MCPyV seroprevalence in the general population is high and increases with age from 50% in childhood to 80% above 50 years.

MCPyV remains latent in immunocompetent hosts, but immunocompromise can lead to viral reactivation (Zwijnenburg, 2021).

Clinical Features of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCC presents as a fast-growing, painless, firm cutaneous nodule. It is classically non-tender and reddish-purple in colour with a shiny surface. They are most commonly located in the head and neck region.

Typical Presentation

MCC presents as a fast-growing, painless, firm cutaneous nodule. It is classically non-tender and reddish-purple in colour with a shiny surface. It can present as a subcutaneous nodule without overlying skin changes (Brady, 2023). Common locations include:

- Head and neck

- Upper limb and shoulder

- Lower limb

- Trunk

There are reported cases in other anatomical regions. These are much less common and include: salivary glands, nasal cavity, oral mucosa, eyelids (mimics chalazia or basal cell carcinoma - North, 2019)

Metastasis

MCC grows quickly and rapidly metastasises (Zwijnenburg, 2021). In some instances, MCC may first be detected as lymph node metastasis without an identifiable primary tumour (Deneve, 2012).

It can locally spread to other areas of the skin, infiltrating via dermal lymphatics and resulting in multiple satellite lesions (Dellambra, 2021). Other locations include:

- Lymph nodes

- Liver

- Lungs

- Bones

- Brain

A mnemonic for summarising typical clinical characteristics of MCC (Heath, 2008):

A - Asymptomatic

E - Expanding rapidly

I - Immunosuppressed

O - Older than 50 years

U - UV-exposed skin

And 90% of patients present with 3 or more of these characteristics.

Association with Other Skin Cancers

MCC can coexist with other types of skin cancers, such as: (Brady, 2023)

- squamous cell carcinoma

- basal cell carcinoma

- sebaceous carcinoma

MCC tumours can also be admixed or adjacent to other skin tumours (NCCN, 2023).

Although overall incidence is relatively rare MCC is the second cause of skin cancer death after melanoma (Harms, 2017).

Diagnosis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

The definitive diagnosis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma relies on histopathology accompanied by an immunohistochemistry panel, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended for all diagnosed patients.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) is diagnosed histopathologically after a lesion raises clinical suspicion. Due to its nonspecific features, timely diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.

Histopathology is essential for confirming a diagnosis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC). The pathology report should include key features with prognostic value:

- Size: Larger tumors (>2cm) are associated with poorer outcomes.

- Peripheral and Deep-Margin Status

- Lymphovascular Invasion (LVI):

- Extracutaneous Extension

- Breslow Depth: Measures tumor thickness from the top of the granular layer of the epidermis (or from the base of an ulcer). This correlates with sentinel lymph node (SLN) positivity, overall survival, and disease-free survival (NCCN, 2023).

Histopathological factors such as increased depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and T-cell infiltration are also linked to poorer outcomes (Zwijnenburg, 2021)

Immunohistochemistry

Histopathological diagnosis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) requires immunohistochemistry to differentiate it from other small cell neoplasms (Brady, 2023), such as:

- Lymphoma

- Ewing Sarcoma

- Neuroblastoma

- Melanoma

- Small Cell Lung Cancer

Once MCC is confirmed by biopsy, additional workup may include:

- Complete History

- Physical Examination: Including skin and lymph nodes.

- Imaging Studies: As clinically indicated, including a CT scan of the chest and abdomen to rule out primary small cell lung cancer and to assess for distant and regional metastasis

Benign Merkel cells are typically located in the basal layer of the epidermis whereas MCC is reported to originate from any layer of the skin (Zwijnenburg, 2021).

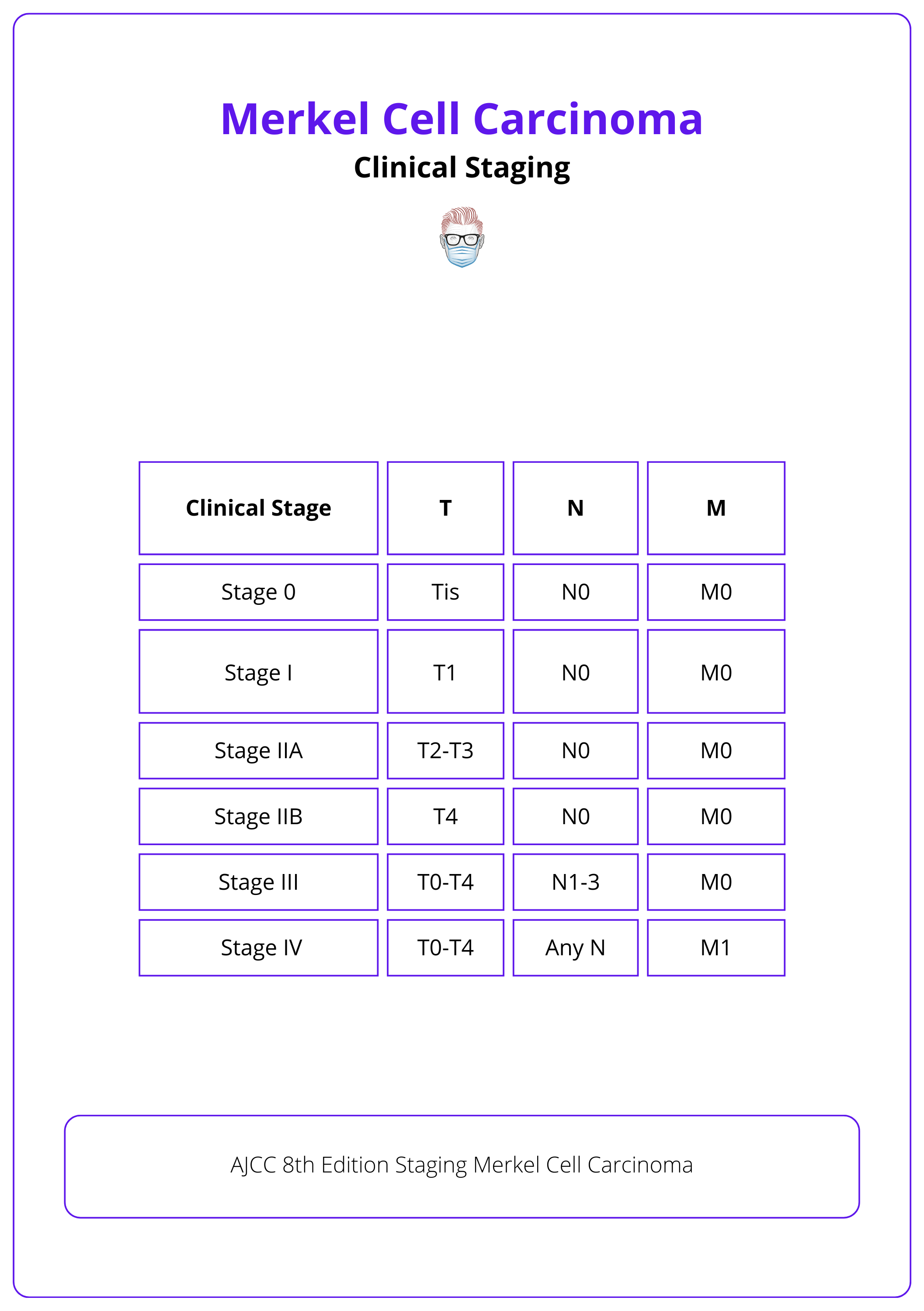

Clinical Staging of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCC is classified and staged from the AJCC 8th edition of 2017.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) is classified and staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition, published in 2017, assessing tumor extent and spread.

Primary Tumor (T)

The staging of the primary tumor in MCC is designated by the 'T' category and is based on the size and extent of the tumor:

- TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed (e.g., curetted).

- T0: No evidence of primary tumor.

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ (localized and not spread).

- T1: ≤2 cm.

- T2: >2 cm but ≤5 cm.

- T3: >5 cm.

- T4: invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone.

Regional Lymph Nodes (N)

Lymph node involvement is categorized under the 'N' staging:

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be clinically assessed (e.g., previously removed for another reason, or because of body habitus).

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination.

- N1: Metastasis in regional lymph node(s).

- N2: In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between the primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) without lymph node metastasis.

- N3: In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumour; located between primary tumour and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumour) with lymph node metastasis.

Distant Metastasis (M)

The presence of distant metastasis is described in the 'M' category:

- M0: No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination.

- M1: Distant metastasis detected.

- M1a: Metastasis to distant skin, subcutaneous tissue, or distant lymph nodes.

- M1b: Metastasis to the lung.

- M1c: Metastasis to all other visceral sites, representing the most advanced stage of disease spread.

The table below illustrates AJCC's 8th Edition Staging of Merkel cell carcinoma.

Treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Treatment of MCC involves excision, +/- SLNB +/- radiotherapy as MCC is very radiosensitive. Immunomodulators have shown promise in treating MCC.

Treating Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) requires a multidisciplinary team focused on patient care. This team typically includes surgeons, radiotherapists, and chemotherapists. Below is the standard treatment protocol according to NCCN, 2023.

Local Disease (Clinical N0)

Surgery

- Excision: Perform 1-2 cm wider local excision or Mohs surgery for precise margin control and tissue preservation (Singh, 2018).

- Delayed Reconstruction is recommended until negative histological margins and SLNB results are confirmed. Simple closures are preferred to facilitate early adjuvant radiotherapy.

Spontaneous MCC regressions have been described after biopsy/complete excision. Likely due to injury leading to inflammation that activate immune anti-tumour responses (Dellambra, 2021).

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB):

- Recommended for clinically node-negative disease.

- Perform at the time of excision or wider local excision (NCCN, 2023).

- If negative, regional recurrence is low, and lymph node region treatment is generally not recommended (Zwijnenburg, 2021).

- If positive, adjuvant radiotherapy or completion lymph node clearance improves overall survival and disease-free survival (Sims, 2018).

Especially for MCC of the head and neck, indications may vary and the risk of false-negative results can be higher (Milhailids, 2021).

Radiotherapy (RT):

- Indicated if surgical margins are positive, if surgery is not feasible, or in cases with adverse features.

- Indicated in a negative SLNB if there is an increased recurrence risk (e.g., unsuccessful SLNB, inappropriate IHC, large tumor, chronic immunosuppression) (Dellambra, 2021).

- If no SLNB is performed, elective treatment of at least the first draining lymph node level by surgery or radiotherapy is recommended (Zwijnenburg, 2021).

Regional Disease (Clinical N+)

- Nodal Dissection: Required following confirmation of positive clinical node.

- Adjuvant Therapy: Consider radiotherapy and systemic therapy if multiple nodes are involved (Zwijenburg, 2021).

Metastatic Disease (Clinical M1)

For patients with metastatic disease systemic therapy, radiation therapy ± surgery may be considered alone or in combination (Brady, 2023). General options to consider include:

- Immunotherapy: Promising responses with PD-1 Pathway Inhibitors (Zwijnenburg, 2021).

- Systemic Therapy: For distant metastases.

- Targeted Radiotherapy/Metastasectomy: Based on MDT recommendations.

- Palliative Care: Manages symptoms and improves quality of life.

Immunotherapy treatments have shown promise and can cause long-lasting responses in a significant proportion of patients with recurrent or metastatic MCC.

Clinical trials utilising immunomodulating agents such as anti-PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies have shown great promise in providing improved progression-free survival (Dasanu, 2019).

Conclusion

1. Understanding Merkel Cell Carcinoma: You've gained insight into the definition, origin, and aggressive nature of MCC, a rare but fast-growing neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin.

2. Risk Factors and Pathogenesis: You've learned about the risk factors for MCC, the influence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), as well as the dual pathogenesis pathways of this cancer.

3. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis: You are now familiar with the typical presentation of MCC and the essential role of histopathology and immunohistochemistry in its diagnosis.

4. Staging and Treatment Options: You've explored the AJCC 8th edition staging for MCC and understand the standard treatments along with the indications for the use of chemotherapy.

5. Prognostic Factors: You've reviewed how factors such as tumor size, lymph node involvement, and patient's immune status influence the prognosis of MCC patients.

Further Reading

- National Cancer Institute Apr 2024. Merkel Cell Carcinoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Accessed on 5th May 2024

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Published November 2023. Accessed 5th May 2024

- Harms PW. Update on Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017 Sep;37(3):485-501. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2017.05.004. Epub 2017 Jun 13. PMID: 28802497.

- Dellambra E, Carbone ML, Ricci F, Ricci F, Di Pietro FR, Moretta G, Verkoskaia S, Feudi E, Failla CM, Abeni D, Fania L. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicines. 2021 Jun 23;9(7):718. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070718. PMID: 34201709; PMCID: PMC8301416.

- Zwijnenburg EM, Lubeek SFK, Werner JEM, Amir AL, Weijs WLJ, Takes RP, Pegge SAH, van Herpen CML, Adema GJ, Kaanders JHAM. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: New Trends. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Mar 31;13(7):1614. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071614. PMID: 33807446; PMCID: PMC8036880.

- Goessling W, McKee PH, Mayer RJ. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Jan 15;20(2):588-98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.588. PMID: 11786590.

- Harms, P.W.; Harms, K.L.; Moore, P.S.; DeCaprio, J.A.; Nghiem, P.; Wong, M.K.K.; Brownell, I.; on behalf of the International Workshop on Merkel Cell Carcinoma Research (IWMCC) Working Group. The biology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: Current understanding and research priorities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 763–776.

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (ed 8th). New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, Nghiem P. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020. PMID: 18280333; PMCID: PMC2335370.

- Brady M, Spiker AM. Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. 2023 Jul 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 29493954.

- Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, Heslin MJ, Bland KI, Beenken SW. Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001 Apr;8(3):204-8. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0204-4. PMID: 11314935.

- Mihailids TH, Dobbs T, Coelho J, Hemington-Gorse S, Cubitt JJ. A letter to the editor: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for Merkel cell carcinoma - A UK-wide perspective. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021 Dec;74(12):3443-3476. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2021.09.013. Epub 2021 Oct 7. PMID: 34697002.

- Dasanu CA, Del Rosario M, Codreanu I, Hyams DM, Plaxe SC. Inferior outcomes in immunocompromised Merkel cell carcinoma patients: Can they be overcome by the use of PD1/PDL1 inhibitors? J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019 Jan;25(1):214-216. doi: 10.1177/1078155218785002. Epub 2018 Jun 22. PMID: 29933728.

- Ma KL, Sharon CE, Tortorello GN, Keele L, Lukens JN, Karakousis GC, Miura JT. Delayed time to radiation and overall survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2023 Dec;128(8):1385-1393. doi: 10.1002/jso.27421. Epub 2023 Aug 25. PMID: 37622232.

- Rotondo JC, Bononi I, Puozzo A, Govoni M, Foschi V, Lanza G, Gafà R, Gaboriaud P, Touzé FA, Selvatici R, Martini F, Tognon M. Merkel Cell Carcinomas Arising in Autoimmune Disease Affected Patients Treated with Biologic Drugs, Including Anti-TNF. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Jul 15;23(14):3929-3934. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2899. Epub 2017 Feb 7. PMID: 28174236.

- Deneve JL, Messina JL, Marzban SS, Gonzalez RJ, Walls BM, Fisher KJ, Chen YA, Cruse CW, Sondak VK, Zager JS. Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Jul;19(7):2360-6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2213-2. Epub 2012 Jan 21. PMID: 22271206; PMCID: PMC4504007.

- Becker JC, Stang A, DeCaprio JA, Cerroni L, Lebbé C, Veness M, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Oct 26;3:17077. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.77. PMID: 29072302; PMCID: PMC6054450.

- Singh B, Qureshi MM, Truong MT, Sahni D. Demographics and outcomes of stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision in the National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jul;79(1):126-134.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.041. Epub 2018 Feb 3. PMID: 29408552.

- North VS, Habib LA, Yoon MK. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019 Sep-Oct;64(5):659-667. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.03.002. Epub 2019 Mar 11. PMID: 30871952.