Summary Card

Overview

Liposuction reshapes contours and aids reconstruction, with advancements like blunt cannulas, wet techniques, and tumescent anesthesia improving results.

Relevant Anatomy

Adipose tissue consists of lobules of adipocytes organized into different layers (apical, mantle, and deep layers). Each layer has unique structural and functional implications in liposuction.

Preoperative Assessment

Assess patient suitability, including factors such as BMI, skin elasticity, and comorbidities. Liposuction has both cosmetic and reconstructive indications.

Surgical Technique

Wetting solutions minimize blood loss and provide anesthesia, while small incisions, blunt cannulas, and assistive technologies enhance liposuction efficiency.

Complications

Complications range from minor contour irregularities and seromas to severe issues like venous thromboembolism (VTE) and fat embolism. Proper technique minimizes risks.

Last Reviewed by: Dr Benedetta Agnelli, Educational Fellow.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

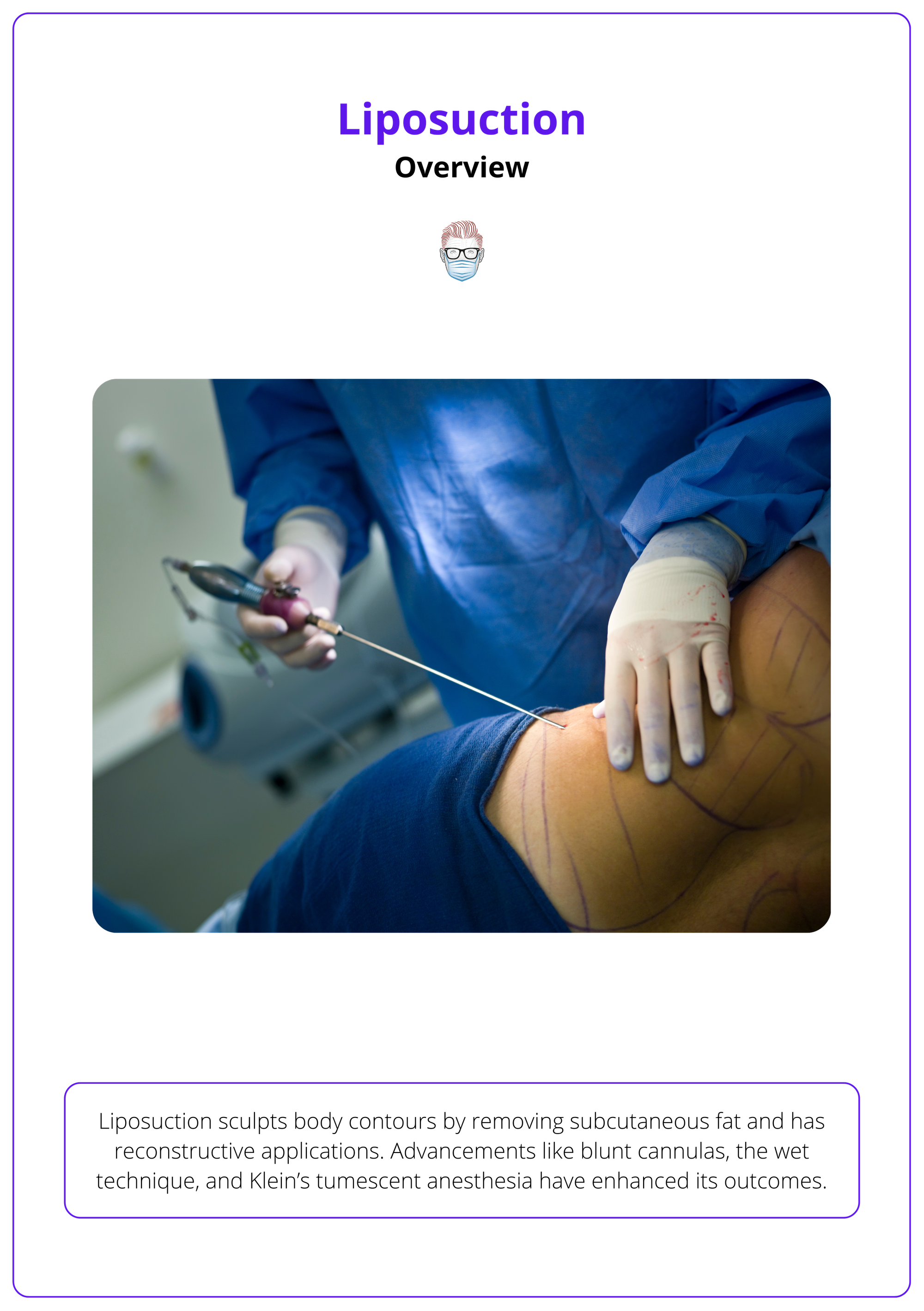

Overview of Liposuction

Liposuction sculpts body contours by removing subcutaneous fat and has reconstructive applications. Advancements like blunt cannulas, the wet technique, and Klein’s tumescent anesthesia have enhanced its outcomes.

Liposuction, also known as suction-assisted lipectomy, is a commonly used procedure for both body contouring and reconstructive surgery. It is the most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedure worldwide (ISAPS Global Survey, 2023).

Advances in technology have improved its safety and effectiveness, allowing for more precise fat removal and enhanced aesthetic outcomes. The primary applications of liposuction include,

- Cosmetic: Body sculpting, fat grafting, gynecomastia/macromastia.

- Reconstructive: Lymphedema, post-traumatic deformities,(e.g., breast reconstruction, scar revision), lipomas, lipodystrophy syndromes.

Liposuction began in 1921 with Dujarrier’s attempt, evolved in the 1970s with modern techniques, and became safer in 1987 with Klein’s tumescent anesthesia.

Relevant Anatomy for Liposuction

Adipose tissue consists of lobules of adipocytes organized into different layers (apical, mantle, and deep layers). Each layer has unique structural and functional implications in liposuction.

Fat layers vary in composition and resistance to suction, making a thorough understanding essential for achieving smooth contours. Different layers and regional variations influence the approach to liposuction, determining safety and effectiveness.

Anatomical Fat Layers

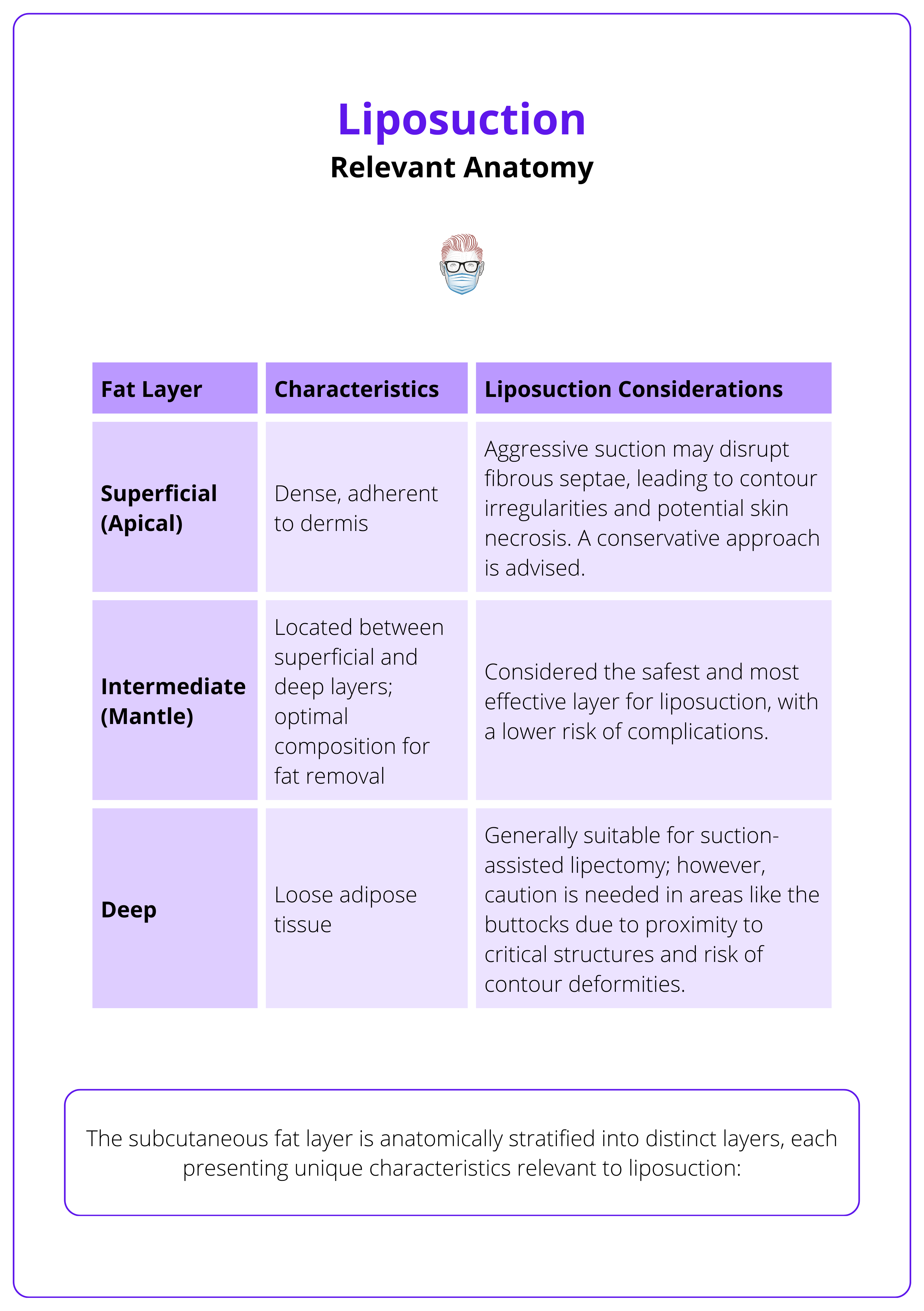

The subcutaneous fat layer is anatomically stratified into distinct layers (Markman, 1987), each presenting unique characteristics relevant to liposuction.

- Superficial (Apical) Layer: This layer is dense and adherent to the overlying dermis. Aggressive suction in this region can disrupt the fibrous septae, leading to contour irregularities and potential skin necrosis. Therefore, the conservative approach is advised when addressing the superficial layer.

- Intermediate (Mantle) Layer: Situated between the superficial and deep layers, the intermediate layer is considered optimal for liposuction. Its composition allows for effective fat removal with a lower risk of complications, making it the primary target in most procedures.

- Deep Layer: Characterized by loose adipose tissue, the deep layer is generally amenable to suction-assisted lipectomy. However, in regions such as the buttocks, caution is warranted due to the proximity of critical structures and the risk of contour deformities.

The characteristics of these layers along with considerations for liposuction are summarized in the table below.

Adipocytes multiply during adolescence (hyperplasia) and expand in size during adulthood (hypertrophy), with liposuction targeting hypertrophic cells to reshape body contours without altering total cell count (Bjorntorp, 1977).

Regional Variations in Adipose Tissue

The distribution, density, and structural composition of adipose tissue vary across different anatomical regions, directly influencing liposuction techniques and outcomes.

- Limbs: Typically contain less fibrous and more superficial adipose tissue, facilitating easier fat extraction. However, preserving lymphatic structures is essential to prevent postoperative lymphedema.

- Back: Contains adipose tissue interspersed with dense fibrous septae, rendering it more resistant to suction. Advanced techniques, such as ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL), can enhance fat emulsification in these fibrous areas, improving outcomes.

Zones of Adherence

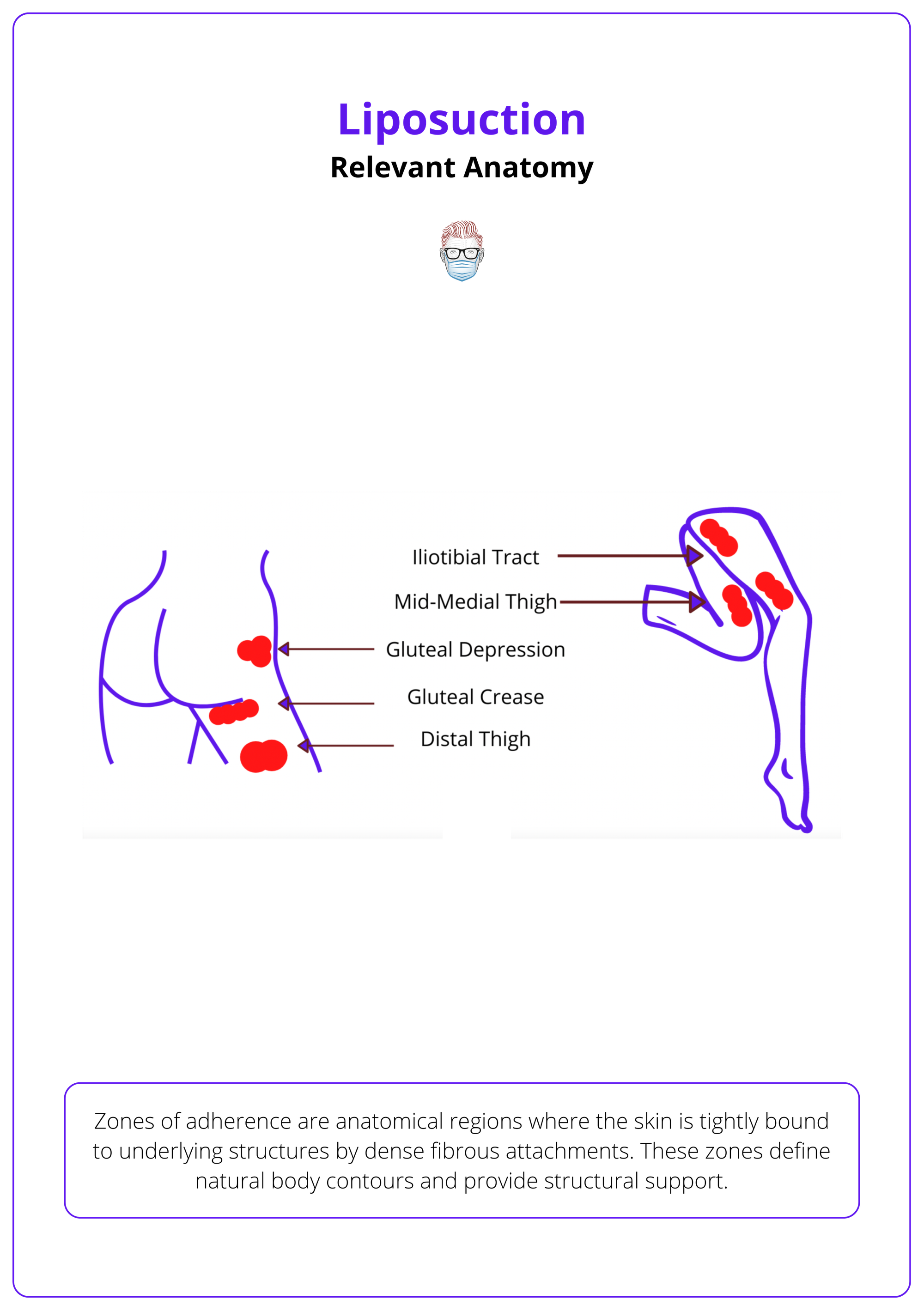

Zones of adherence are anatomical regions where the skin is tightly bound to underlying structures by dense fibrous attachments (Rohrich, 1999). These zones define natural body contours and provide structural support. Key zones include,

- Distal Iliotibial Tract: Located along the lateral aspect of the thigh, this zone contributes to the smooth contour of the outer thigh.

- Gluteal Crease: The natural fold beneath the buttocks, essential for defining the lower boundary of the gluteal region.

- Lateral Gluteal Depression: Situated over the greater trochanter, this area influences the contour of the hip.

- Middle Medial Thigh: The inner thigh region, where adherence zones affect the medial contour.

- Distal Posterior Thigh: The back of the thigh near the knee, where fibrous attachments impact the posterior leg silhouette.

Aggressive liposuction in these areas can disrupt these attachments, leading to contour deformities and other complications. The relevant anatomical zones of adherence for liposuction are illustrated below.

Preoperative Assessment for Liposuction

For optimal liposuction outcomes, conduct a comprehensive preoperative assessment focusing on patient expectations, medical history, BMI (preferably ≤30), skin elasticity, and fat distribution.

Liposuction is most effective for patients near their ideal body weight, ideally within 20-30% of their ideal BMI, with good skin elasticity. A meticulous preoperative assessment helps identify suitable candidates and mitigate potential risks.

Clinical History

- Patient Expectations and Motivations: Understanding the patient's goals ensures realistic expectations and satisfaction with the surgical outcome.

- Medications: Certain medication can increase surgical risks. For instance, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may elevate bleeding risk and influence lidocaine metabolism, potentially leading to toxicity.

- Smoking Status: Smoking adversely affects wound healing and increases the risk of complications. Patients are strongly advised to cease smoking at least four weeks prior to surgery.

- Comorbidities: Conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and coagulopathies can elevate surgical risks.

Physical Examination

- Body Mass Index (BMI): While there is no strict BMI cutoff, patients with a BMI ≤30 are generally considered optimal candidates.

- Skin Elasticity: Good skin elasticity is vital for achieving desirable postoperative contouring. Liposuction does not address skin laxity; therefore, patients may require additional procedures.

- Fat Distribution and Quality: Assess thickness, symmetry and location of subcutaneous fat. Notably, liposuction may not improve the appearance of cellulite and, in some cases, could exacerbate its appearance.

- Abdominal Pathology: Existing scars can alter normal anatomy and affect fat distribution, potentially complicating the procedure. The presence of hernias or muscle separation should be identified and addressed appropriately.

Laboratory and Ancillary Investigations

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To identify anemia or infection.

- Coagulation Profile: To detect any bleeding disorders that could increase surgical risk.

- Metabolic Panel: To assess kidney and liver function, ensuring the patient can safely undergo anesthesia and metabolize medications used during the procedure.

In certain cases, additional investigations such as electrocardiograms or imaging studies may be warranted based on the patient's medical history and physical examination findings.

Ideally, patients have adequate skin elasticity and are within 20% to 30% of their ideal body weight to achieve desired aesthetic outcomes (Benatti, 2011).

Surgical Technique for Liposuction

Liposuction uses wetting solutions like Klein's and Hunstadt's for hemostasis and anesthesia. Techniques involve small incisions, blunt cannulas, and assistive technologies (power-assisted, laser, ultrasound).

Liposuction utilizes different wetting solutions (Klein's, Hunstadt's) to optimize blood loss and anesthesia. Techniques involve small incisions, blunt-tip cannulas, and assistive technologies.

Wetting Solutions & Anesthetic Techniques

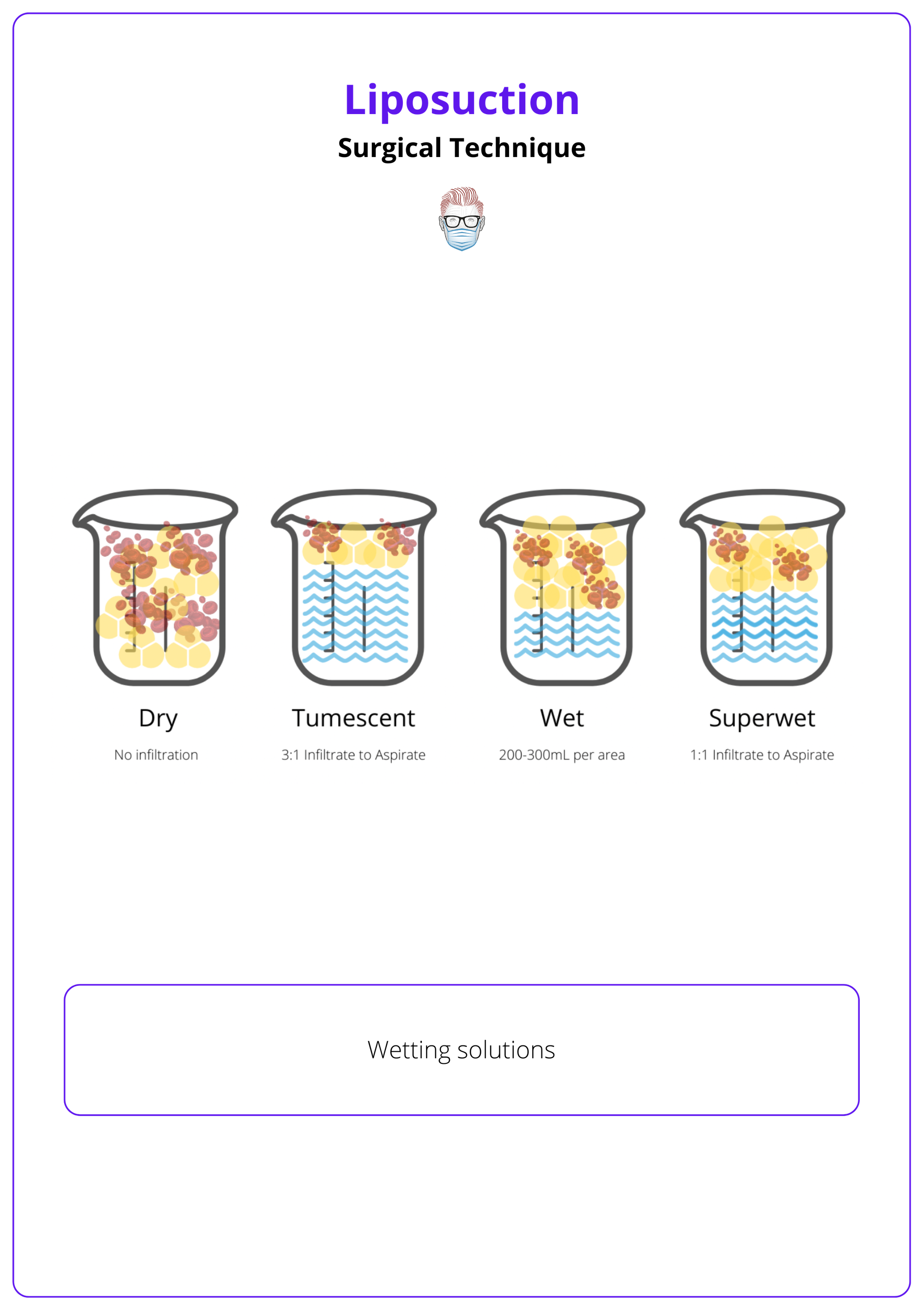

The wetting solutions for liposuction can be classified into 4 main groups and they differ in the amount of infiltration and the degree of blood loss:

- Dry Technique: No infiltration, 25–40% blood loss. No longer used.

- Wet Technique: 200–300 mL infiltrate per area, 4–30% blood loss.

- Superwet Technique: 1:1 infiltrate-to-aspirate ratio, ~1% blood loss.

- Tumescent Technique: 2–3:1 infiltrate-to-aspirate ratio, ~1% blood loss.

Most commonly used solutions:

- Klein’s Solution: 1L normal saline, 50 mL 1% Lidocaine, 0.65 mg (1 mL 1:1000) Epinephrine and 10mEq/L (12.5 mL of 8.4%) Sodium Bicarbonate (Klein 1990).

- Hunstadt’s Solution: 1L Ringer's Lactate, 500mg Lidocaine, 1mg Epinephrine.

Lidocaine provides local anesthesia with a maximum safe dose of 7 mg/kg, while epinephrine minimizes blood loss, safely used up to 10 mg/kg. Wetting solutions for liposuction are illustrated below.

Alkalization with sodium bicarbonate may decrease pain with infiltration but it is not needed with general anesthesia.

Surgical Steps

- Incision Placement: Strategically made within natural creases to minimize visible scarring.

- Cannulation: Insertion of blunt-tip cannulas of varying diameters; smaller cannulas allow for more even fat removal but increase resistance.

- Infiltration: Administering the wetting solution until tissue blanching and moderate tension are observed.

- Aspiration: Removing fat primarily from deep and intermediate layers; superficial fat is addressed cautiously to prevent contour irregularities.

- Closure: Massaging to expel excess fluid followed by suturing.

- Postoperative Care: Application of compression garments and foam to support tissue adherence and reduce swelling.

A Technique For Liposuction

Smaller cannulas = more even fat removal.

Shorter cannulas = better control.

Increased resistance as cannula diameter decreases.

Assistive Technologies

New technologies to assist in liposuction have been developed.

- Suction-Assisted Liposuction (SAL): Standard technique (Prado, 2006).

- Power-Assisted Liposuction (PAL): Reduces surgeon fatigue (Young, 2001).

- Laser-Assisted Liposuction (LAL): Helps emulsify fat.

- Ultrasound-Assisted Liposuction (UAL): Minimizes blood loss and improves fat extraction.

Complications of Liposuction

Liposuction carries risks ranging from minor contour irregularities to severe complications like fat embolism and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

While liposuction is generally safe, complications can occur. A study reported an overall complication rate of approximately 2.4%, with higher rates observed when liposuction is combined with other procedures (Viera, 2018).

Common Complications

- Minor Issues: Bruising (ecchymosis), swelling (edema), infection, seroma, hematoma, and temporary numbness (paresthesia).

- Contour Deformities: Occur in up to 9% of patients, leading to uneven or irregular skin surfaces.

- Skin Necrosis: Rare but serious, involving the death of skin cells due to inadequate blood supply.

- Venous Thromboembolism (VTE): Includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism; though uncommon, they are serious and require prompt treatment.

- Fat Embolism: Rare but potentially fatal, with a mortality rate between 10-15% (Grazer, 2000).

- Visceral Perforation: Accidental injury to internal organs, necessitating immediate surgical intervention.

Long-Term Issues

- Skin Laxity: Loose or sagging skin post-procedure, especially if significant fat was removed.

- Hypertrophic Scarring: Thickened, raised scars that may develop at incision sites.

- Hyperpigmentation: Darkening of the skin in treated areas, which may persist over time.

By adhering to meticulous surgical techniques and thorough patient evaluation, the incidence of complications can be minimized, ensuring safer outcomes for those undergoing liposuction.

For aspirate volumes less than 5 liters, maintain fluid balance with maintenance fluids and subcutaneous infiltrate. For volumes exceeding 5 liters, additional intravenous fluids may be necessary.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Liposuction removes subcutaneous fat for body contouring and reconstructive applications, including lymphedema and fat grafting. Advancements such as blunt cannulas, the wet technique, and Klein’s tumescent anesthesia have improved safety and efficacy.

2. Relevant Anatomy: Adipose tissue is organized into apical, mantle, and deep layers, each with different properties affecting suctioning. Zones of adherence, where fibrous tissue anchors fat, should be avoided to prevent contour deformities.

3. Preoperative Assessment: Ideal candidates are within 20-30% of their ideal BMI with good skin elasticity. Key considerations include medical history, medications, smoking, and comorbidities. Liposuction is used for both cosmetic and reconstructive purposes, such as lipomas, lipedema, and gynecomastia.

4. Surgical Technique: Liposuction involves small incisions, blunt cannulas, and wetting solutions (tumescent, superwet) to minimize blood loss. Advanced methods include power-assisted, laser-assisted, and ultrasound-assisted liposuction to enhance fat removal and precision.

5. Safety and Complications: Risks include bruising, seroma, contour irregularities, venous thromboembolism, and fat embolism. Proper patient selection, technique, and postoperative care reduce complications and improve outcomes.

Further Reading

- Wrighton SA, Stevens JC. The human hepatic cytochromes P450 involved in drug metabolism. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1992;22:1–21.

- Rinker B. The evils of nicotine: An evidence-based guide to smoking and plastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70:599–605.

- Rohrich RJ, Beran SJ, Fodor PB. The role of subcutaneous infiltration in suction-assisted lipoplasty: A review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:514–519; discussion 520–526.

- Rohrich, R. J., Smith, P. D., Marcantonio, D. R., & Kenkel, J. M. (2001). The Zones of Adherence: Role in Minimizing and Preventing Contour Deformities in Liposuction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 107(6), 1562–1569.doi:10.1097/00006534-200105000-00043

- Klein JA. The tumescent technique for liposuction surgery. Am J Cosm Surg. 1987;4:263–7.

- Lynch, D. J., Iverson, R. E., and the American Society of Plastic Surgeons Committee on Patient Safety. Practice ad- visory on liposuction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 113: 1478; discus- sion 1491; discussion 1494, 2004.

- Matarasso A. Superwet anesthesia redefines large-volume liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 1997;17:358–364.

- Fodor PB, Vogt PA. Power-assisted lipoplasty (PAL): A clini- cal pilot study comparing PAL to traditional lipoplasty (TL). Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999;23:379–385.

- Tark KC, Jung JE, Song SY. Superior lipolytic effect of the 1,444 nm Nd:YAG laser: Comparison with the 1,064 nm Nd:YAG laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:721–727.

- Hughes CE III. Reduction of lipoplasty risks and mortality: An ASAPS survey. Aesthet Surg J. 2001;21:120–127

- Kaoutzanis C, Gupta V, Winocour J, et al. Cosmetic lipo- suction: Preoperative risk factors, major complication rates, and safety of combined procedures. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:680–694.

- Grazer FM, de Jong RH. Fatal outcomes from liposuction: Census survey of cosmetic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:436–446; discussion 447

- Prins MH, Hirsh J. A comparison of general anesthesia and regional anesthesia as a risk factor for deep vein thrombo- sis following hip surgery: A critical review. Thromb Haemost. 1990;64:497–500.

- Phillip J. Stephan, MD, FACS, Jeffrey M. Kenkel, MD, FACS, Updates and Advances in Liposuction, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 30, Issue 1, January 2010, Pages 83–97, https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X10362728

- Gasperoni C, Gasperoni P. Subdermal liposuction: long-term experience. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2006 Jan;33(1):63-73, vi. DOI: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.08.006.

- Rohrich RJ, Leedy JE, Swamy R, Brown SA, Coleman J. Fluid resuscitation in liposuction: A retrospective review of 89 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:431–435.

- Pitman GH, Aker JS, Tripp ZD. Tumescent liposuction: A surgeon’s perspective. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:633–641; dis- cussion 642.

- Matarasso A. Superwet anesthesia redefines large-volume liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 1997;17:358–364

- Klein JA. Tumescent liposuction and improved postopera- tive care using tumescent liposuction garments. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:329–338.

- Theodorou S, Chia C. Radiofrequency-assisted liposuction for arm contouring: Technique under local anesthesia. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2013;1:e37.

- Yin S, Luan J, Fu S, Wang Q, Zhuang Q. Does water-jet force make a difference in fat grafting? In vitro and in vivo evi- dence of improved lipoaspirate viability and fat graft survival. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:127–138.

- Fisher C, Grahovac TL, Schafer ME, Shippert RD, Marra KG, Rubin JP. Comparison of harvest and processing techniques for fat grafting and adipose stem cell isolation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:351–361.

- Lehnhardt M, Homann HH, Daigeler A, Hauser J, Palka P, Steinau HU. Major and lethal complications of liposuction: A review of 72 cases in Germany between 1998 and 2002.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:396e–403e.

- Hanke CW, Bernstein G, Bullock S. Safety of tumescent liposuction in 15,336 patients: National survey results. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:459–462.

- Prins MH, Hirsh J. A comparison of general anesthesia and regional anesthesia as a risk factor for deep vein thrombo- sis following hip surgery: A critical review. Thromb Haemost.1990;64:497–500.

- Wu S, Coombs DM, Gurunian R. Liposuction: Concepts, safety, and techniques in body-contouring surgery. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020 Jun;87(6):367-375. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.19097. Erratum in: Cleve Clin J Med. 2020 Jul 31;87(8):476. PMID: 32487557.

- Stein MJ, Matarasso A. High-Definition Liposuction in Men. Clin Plast Surg. 2022 Apr;49(2):307-312. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2022.01.003. PMID: 35367037.

- Beidas OE, Gusenoff JA. Update on Liposuction: What All Plastic Surgeons Should Know. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Apr 1;147(4):658e-668e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007419. PMID: 33776041.