Summary Card

Overview

Flap vascular compromise (arterial ischaemia or venous congestion) is a time‑critical surgical emergency that most often arises within the first 72 hours post‑operatively and requires rapid recognition to maximise salvage.

Aetiology

Flap compromise results from mechanical obstruction, thrombosis, or rheological disturbances. Venous congestion is more common and often more insidious than arterial ischaemia, demanding urgent intervention.

Pathophysiology

Flap compromise initiates a cascade of hypoxia, capillary leak, microvascular thrombosis, and inflammation, progressing rapidly within hours and exacerbated by delayed choke vessel recruitment and non-occlusive flow disturbances.

Classification

Although no single, universally accepted system exists, grouping flap compromise by timing, type of vascular insufficiency, and extent of tissue involvement provides a practical framework for diagnosis and management.

Clinical Assessment

Early, structured clinical assessment including history, examination, and adjunct monitoring remains the cornerstone of detecting vascular compromise and maximising flap salvage.

Investigations

Clinical assessment is key to flap monitoring, but real-time modalities such as Doppler and NIRS can detect early compromise. Blood tests and imaging play supportive roles in select cases, and should never delay surgical re-exploration if acute compromise is strongly suspected.

Management

Flap salvage depends on early recognition and prompt action. Surgical re-exploration remains the mainstay for mechanical causes, while non-surgical strategies may support venous drainage when revision is not feasible or no structural issue is found.

Prognosis

Flap salvage is time-dependent. Early recognition and revision within 6 hours offer the best chance of success, while delayed intervention or repeated compromise significantly lowers survival.

Primary Contributor: Hatan Mortada, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Ischaemic and Congested Flaps

Flap vascular compromise (arterial ischaemia or venous congestion) is a time‑critical surgical emergency that most often arises within the first 72 hours post‑operatively and requires rapid recognition to maximise salvage.

Flap vascular compromise refers to insufficient arterial inflow (ischaemia) or impaired venous outflow (congestion) in a surgical flap. Flap vascular compromise typically occurs early in the post-operative period (<72 hours), is the most frequent cause of early flap failure, and demands urgent surgical attention to preserve flap viability.

These complications can affect both free and pedicled flaps, each with distinct clinical features.

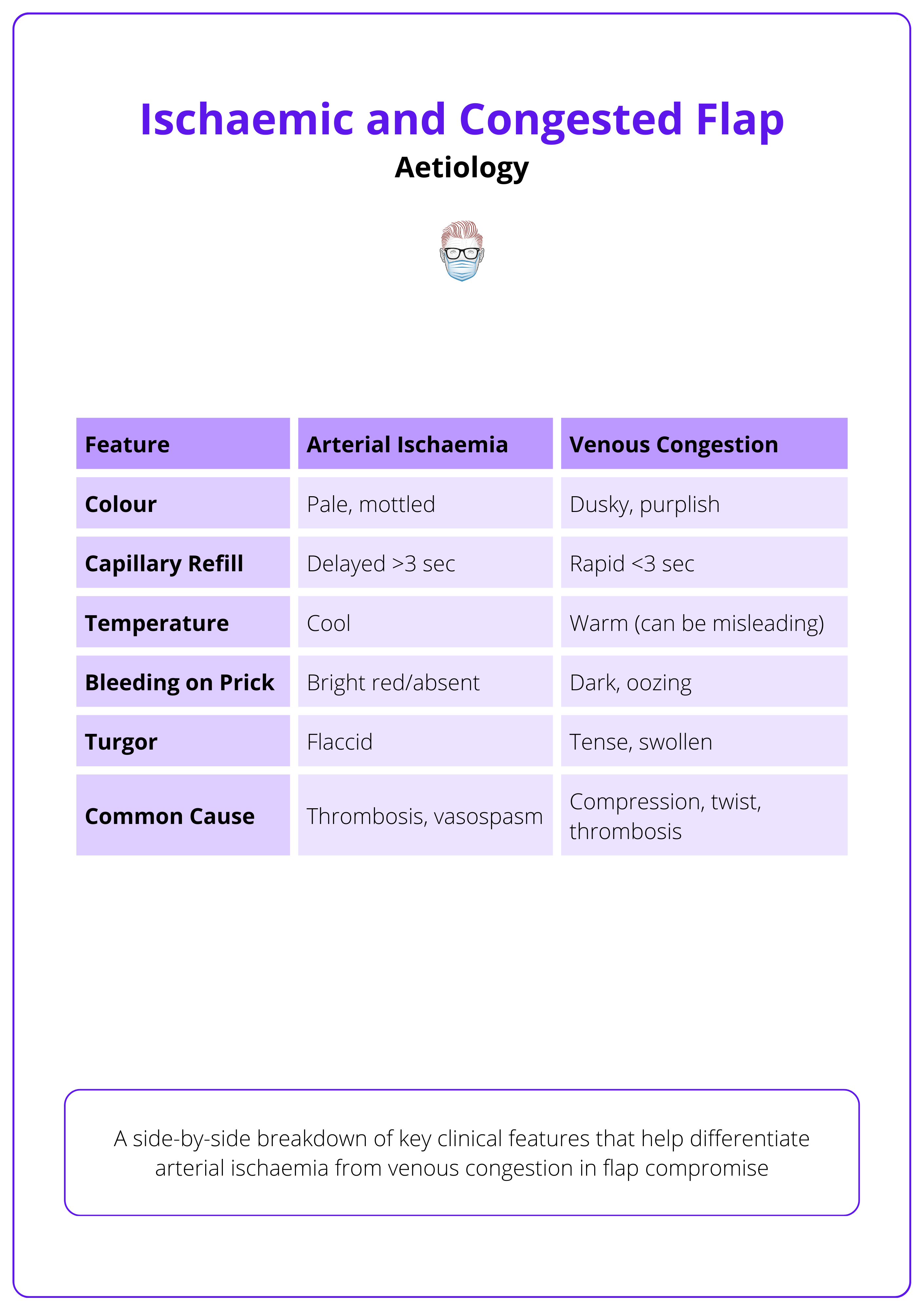

- Ischaemia: Pale, cold, delayed capillary refill, no bleeding on needle prick.

- Congestion: Purplish hue, rapid refill (<3s), dark venous bleeding, tense swelling.

Venous congestion is more common than arterial ischaemia and is often more challenging to manage (Shen, 2021; Coriddi, 2023).

In 1972, surgeons performed the first successful free flap, transplanting vascularized tissue from the groin to the ankle, revolutionizing reconstructive surgery with microsurgical precision.

Aetiology of Ischaemic and Congested Flaps

Flap compromise results from mechanical obstruction, thrombosis, or rheological disturbances. Venous congestion is more common and often more insidious than arterial ischaemia, demanding urgent intervention.

Flap vascular compromise arises due to disruptions in either arterial inflow or venous outflow, often dictated by intraoperative technique, flap design, and patient-specific factors.

Arterial Ischaemia

Thrombosis at the Arterial Anastomosis typically stems from technical errors such as poor suture placement, tension, or rough handling that causes intimal trauma.

- Vasospasm: Provoked by vessel manipulation, hypothermia, or trauma. Particularly relevant in small-calibre vessels.

- Pedicle Kinking or Torsion: Results from improper flap positioning, especially when the vascular pedicle is looped or twisted during inset.

- Clot Propagation: May follow intimal injury or occur secondary to inadequate anticoagulation, progressing proximally or distally along the vessel.

Venous Congestion

- Mechanical Compression: Caused by tight dressings, bulky hematomas, or pressure from tunneled pathways.

- Pedicle Twisting: A frequent complication in propeller or island flaps, where flap rotation places torque on the venous system.

- Venous Thrombosis: Often occurs at the anastomosis or within small venules, leading to rapid flap congestion and failure.

- Inadequate Venous Outflow: Poor vein selection, size mismatch, or anatomic variation can hinder drainage and promote stasis.

The table below summarises the differences between arterial ischaemia and venous congestion.

Pathophysiology of Ischaemic and Congested Flaps

Flap compromise initiates a cascade of hypoxia, capillary leak, microvascular thrombosis, and inflammation, progressing rapidly within hours and exacerbated by delayed choke vessel recruitment and non-occlusive flow disturbances.

Both ischaemia and congestion initiate a cascade of events that compromise flap viability, beginning at the microvascular level.

- Initial Vascular Obstruction: Leads to tissue hypoxia and, in venous congestion, early stasis.

- Capillary Leak and Cellular Injury: Hypoxia-induced endothelial damage results in fluid extravasation, edema, and cellular breakdown.

- Microvascular Thrombosis: Particularly critical after 6–8 hours, this exacerbates hypoxia and reduces chances of flap salvage (Chen, 2007).

- Inflammatory Cascade: Drives further edema, elevates interstitial pressure, and compresses microcirculation.

- Choke Vessel Recruitment: Occurs later as a compensatory mechanism to redistribute flow between angiosomes, mainly relevant in delayed congestion.

- Non-Occlusive Factors: Flow turbulence, altered shear stress, and rheological changes can mimic thrombosis, complicating diagnosis and management.

Not all venous congestion is true thrombosis. Phenomena such as flow redistribution, choke vessel opening, and transient turbulence can mimic congestion without actual vessel occlusion.

Classification of Flap Compromise

Although no single, universally accepted system exists, grouping flap compromise by timing, type of vascular insufficiency, and extent of tissue involvement provides a practical framework for diagnosis and management.

While arterial and venous classifications are commonly used to describe flap failure, other classification methods also exist—though they are not universally adopted. A more practical approach categorizes flap compromise based on three factors: timing (when it occurs), and extent (how much of the flap is affected).

Timing of Compromise

Timing influences both the cause and urgency of treatment, with early recognition offering the highest chance of flap salvage.

- Immediate (Intra-operative): Usually technical errors such as kinking or misalignment. High salvage potential if corrected during surgery.

- Early (0–72 hours Post-op): Most common window for vascular compromise. Rapid onset events like thrombosis or twisting occur here. Prompt re-intervention can result in up to 70% salvage success.

- Delayed (>72 hours Post-op): Often secondary to infection, compression, or late thrombosis. Salvage rates decline significantly due to compounded tissue damage.

Extent of Tissue Involvement

Describing the distribution of compromise — whether global or segmental — helps assess severity and salvage potential.

- Global Compromise: Entire flap is ischaemic or congested. Typically occurs from major vessel thrombosis and is seen early post-op.

- Distal or Segmental Compromise: Affects flap tip or isolated zone. More common in late or partial venous issues and may mimic low-grade congestion.

Special Consideration: Early vs. Late Congestion

- Early Congestion: Often due to large vessel thrombosis, leading to rapid onset global flap congestion.

- Late Congestion: Typically microvascular in nature, involving distal zones. Presents subtly and can be mistaken for non-occlusive or inflammatory congestion.

What looks like venous congestion in the first 24 hours might just be transient hyperaemia or pseudo-congestion. This self-limiting state results from flow turbulence or early vasodilatation. Serial assessments help avoid unnecessary re-exploration.

Clinical Assessment for Flap Compromise

Early, structured clinical assessment including history, examination, and adjunct monitoring remains the cornerstone of detecting vascular compromise and maximising flap salvage.

History

Careful history-taking pinpoints the onset and context of flap issues.

- Timing: Most complications arise within 72 hours post-surgery (Shen, 2021).

- Symptoms (Sensate Flaps): Increased pain or pressure reported by patients.

- Operative Factors: Flap type (e.g., free vs. pedicled), tunneling, prior revisions, anticoagulation use.

- Systemic Risks: Hypotension, vasopressor exposure, coagulopathy, smoking, or diabetes.

Examination

A structured examination is performed hourly for the first 24 h, then tapered.

Venous Congestion Signs

- Color: Dusky or purplish hue

- Capillary Refill: Brisk (<3 seconds)

- Bleeding: Dark, deoxygenated blood on pinprick

- Turgor: Swollen, tense flap

- Temperature: Warm (may mislead if isolated)

Arterial Ischemia Signs

- Color: Pale or mottled appearance

- Capillary Refill: Delayed (>3 seconds)

- Bleeding: Absent or minimal bright red blood

- Turgor: Flaccid, soft flap

- Temperature: Cool or cold to touch

Adjuncts

- Handheld Doppler: Assesses pedicle patency.

- Implantable Doppler: Monitors arterial and venous flow.

- Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): Tracks oxygenation continuously.

Risk Factors

Certain conditions increase the likelihood of flap failure.

- Smoking and Diabetes: Impair microvascular function.

- Previous Radiotherapy: Causes vessel fibrosis and delayed healing.

- Hypercoagulable States: Elevate thrombosis risk (e.g., Factor V Leiden).

- Obesity or Large Flaps (e.g., TRAM, DIEP): Prone to congestion.

- Long Pedicles or Multiple Anastomoses: Raise technical failure odds.

Differential Diagnosis

Not all flap changes indicate vascular issues. Differential diagnosis considers,

- Hematoma: Compresses pedicle, mimics congestion.

- Seroma: Fluid collection in loose tissue beds.

- Flap Edema: Normal post-op, lacks rapid progression.

- Infection: Onset >48–72 hours, with fever or systemic signs.

- Pseudo-Congestion: Capillary hyperemia or turbulence (no thrombosis).

Early post‑op flaps may appear compromised. Correlate findings with serial exams and timing to avoid unnecessary re‑exploration.

Investigations for Flap Compromise

Clinical assessment is key to flap monitoring, but real-time modalities such as Doppler and NIRS can detect early compromise. Blood tests and imaging play supportive roles in select cases, and should never delay surgical re-exploration if acute compromise is strongly suspected.

Clinical examination is the gold standard. Imaging tools and monitoring devices can provide additional insights, especially when the diagnosis is unclear or the flap is buried.

Blood Tests

Routine labs uncover contributing factors.

- Full Blood Count: Screens for anemia or infection.

- Coagulation Profile: Rules out clotting disorders.

- CRP & ESR: Tracks inflammation or infection in delayed cases.

- Thrombophilia Screen: Probes unexplained thrombosis (e.g., in young patients).

Order a thrombophilia workup if flaps fail despite sound technique and anticoagulation.

Imaging

Used selectively when clinical findings are ambiguous.

- Doppler Ultrasound (Handheld/Duplex): Checks arterial and venous signals.

- CT Angiography: Evaluates late failure, especially in buried flaps.

- MRI with Contrast: Assesses deep infections or complex reconstructions.

Other Monitoring Tools

Common tools for flap surveillance.

- Handheld Doppler: Quick bedside patency check.

- Implantable Doppler: Continuous arterial/venous monitoring.

- Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS): Non-invasive oxygenation tracking.

- Pinprick Test: Assesses bleeding quality and perfusion.

Monitoring Pearls

- Use multiple tools to avoid false negatives.

- NIRS excels at detecting venous congestion early.

Serial pinprick tests can outperform Doppler for venous congestion assessment. Doppler flow may sound acceptable while actual perfusion is still insufficient!

Management of Flap Compromise

Flap salvage depends on early recognition and prompt action. Surgical re-exploration remains the mainstay for mechanical causes, while non-surgical strategies may support venous drainage when revision is not feasible or no structural issue is found.

Management of flap vascular compromise hinges on understanding the cause (arterial, venous, or both), identifying mechanical versus microvascular problems, and acting swiftly. Time is tissue: early intervention is critical to improve salvage rates, particularly in free flaps.

At the Bedside

Before rushing to theatre, a systematic bedside assessment can yield crucial information and sometimes resolve reversible issues.

- Check Patient Vitals: Hypotension or hypoxia can exacerbate ischaemia. Address any systemic instability that might impact perfusion. Assess Urine Output as a practical measure of systemic perfusion and volume status.

- Remove Tight Dressings or Sutures: Loosen any compressive garments or sutures that may restrict venous outflow.

- Maintain Optimal Positioning: Keep the flap dependent and uncovered to encourage venous drainage. Avoid kinking or flexion near pedicles.

- Stop Cooling and Keep Warm: Vasospasm can be aggravated by cold. Apply gentle warming and maintain a neutral thermal environment.

- Communicate and Consent: Alert the surgical team early. If re-exploration is likely, obtain informed consent and prepare for theatre.

Surgical Management

If flap compromise is suspected, surgical re-exploration is the first-line treatment.

Emergency Re-Exploration

- Hematoma or tight inset compressing the pedicle

- Twisting, kinking, or vasospasm

- Thrombosis at the anastomosis

Pedicled Flaps

- Reposition or untwist the pedicle (common in propeller flaps)

- Reopen inset or add venous supercharging to improve drainage

Free Flaps

- Revise anastomoses, checking for thrombus or vasospasm

- Perform thrombectomy using Dumont forceps or a Fogarty catheter

- Consider thrombolysis (e.g., intra-arterial Actilyse 2 mg with venous outflow open)

- Use vein grafting or alternate recipient vessels if structural damage is severe

Most flap salvages occur in the operating room. Early surgical take-back offers the best chance of success and delays beyond 6 hours significantly reduce flap survival.

Non-Surgical Management

Used primarily for venous congestion when mechanical issues are excluded or surgical re-exploration is not feasible.

Leech Therapy (Hirudotherapy)

Gold standard for passive drainage and anticoagulation.

- Effectiveness: ~70% success; lower (~30%) in bulky flaps like TRAM/DIEP (Slijepcevic, 2022).

- Risks: Bleeding, Aeromonas infection (prophylactic ciprofloxacin recommended).

Chemical Leeching

Subcutaneous LMWH with scarification (superficial dermal cuts).

- Useful for small flaps.

- Requires intensive nursing; risk of bleeding.

Venocutaneous Catheterization

Cannulates superficial flap vein for controlled drainage.

- Near 100% success in small series (Okazaki, 2007).

- Safer and more controlled than leeches but needs pre-planning.

Negative Pressure Therapy (NPT)

Enhances venous return and reduces flap edema.

- Particularly useful in trauma-related flaps.

- Use intermittent suction to avoid compromising arterial inflow.

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT)

Experimental; not routinely recommended for flap salvage.

- Limited evidence of benefit in venous congestion.

Prognosis of Flap Compromise

Flap salvage is time-dependent. Early recognition and revision within 6 hours offer the best chance of success, while delayed intervention or repeated compromise significantly lowers survival.

Outcomes

Flap viability is closely tied to the timing of diagnosis and management.

- Early Revision (within 6 hours): 60–70% salvage success rate (Chen, 2007).

- Delayed Recognition (>6–8 hours): Causes irreversible microvascular damage (Chen,2007).

- Venous vs. Arterial: Venous congestion has a poorer prognosis due to insidious onset and microcirculatory failure.

- Recurrence Impact: First episode salvage ~60–70%, second ~30%, third rarely salvageable (Odorico, 2023).

- Context: Free flaps succeed in ~95% of cases, but 10% need revision—most salvageable if acted on quickly.

Complications

Even with flap survival, complications can develop locally or systemically.

- Local Complications

- Partial or Total Flap Loss: Often linked to delayed revision.

- Flap Necrosis: May require further debridement and secondary reconstruction.

- Infection: Especially Aeromonas infections after leech therapy.

- Wound Breakdown: Common in irradiated tissue or high-tension closures.

- Edema or Hematoma: Can trigger further vascular compromise if not addressed.

- Systemic Complications

- Blood Loss: Seen with extensive leeching or chemical scarification.

- Sepsis: Rare, but possible if infections are missed or untreated.

- Thromboembolic Events: Associated with aggressive anticoagulation protocols.

Flap failures occurring after discharge (typically after day 7) are rarely salvageable. Causes include infection, pressure during sleep, or late thrombosis, not purely vascular issues. Patients should be clearly counselled on warning signs before leaving hospital.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Flap vascular compromise refers to impaired blood flow within a flap, typically due to arterial ischaemia or venous congestion, and most commonly occurs within the first 72 hours post-op.

2. Aetiology & Pathophysiology: Causes include pedicle kinking, thrombosis, or compression, leading to hypoxia, edema, and microvascular clotting. Venous congestion is more frequent and harder to manage than arterial insufficiency.

3. Clinical Assessment: Diagnosis relies on flap colour, capillary refill, and pinprick testing, supported by Doppler or NIRS. Risk factors include smoking, radiotherapy, large flap volume, and coagulopathies.

4. Investigations: While clinical signs are primary, adjuncts like implantable Dopplers, coagulation screens, and venous imaging may aid in complex or delayed presentations.

5. Management & Prognosis: Surgical revision remains the mainstay for mechanical causes; medical salvage (e.g. leeches, heparin injections) is used when revision is not feasible. Salvage rates drop significantly after 6–8 hours or with recurrent compromise.

Further Reading

- Chen KT, Mardini S, Chuang DC, et al. Timing of presentation of the first signs of vascular compromise dictates the salvage outcome of free flap transfers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(1):187-195. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000264077.07779.50

- Khansa I, Chao AH, Taghizadeh M, Nagel T, Wang D, Tiwari P. A systematic approach to emergent breast free flap takeback: clinical outcomes, algorithm, and review of the literature. Microsurgery. 2013;33(7):505-513. doi:10.1002/micr.22151

- Chang EI, Chang EI, Soto-Miranda MA, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of risk factors and management of impending flap loss in 2138 breast free flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77(1):67-71. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000263

- Shen AY, Lonie S, Lim K, Farthing H, Hunter-Smith DJ, Rozen WM. Free flap monitoring, salvage, and failure timing: a systematic review. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2021;37(4):300-308. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1717141

- Slijepcevic AA, Yang S, Petrisor D, Chandra SR, Wax MK. Management of the failing flap. Semin Plast Surg. 2023;37(1):19-25. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1759563

- Hara H, Mihara M, Narushima M, et al. Predictors, management and prognosis of initial hyperemia of free flap. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):3678. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54321-5

- Odorico SK, Reuter Muñoz K, Nicksic PJ, et al. Surgical and demographic predictors of free flap salvage after takeback: a systematic review. Microsurgery. 2023;43(1):78-88. doi:10.1002/micr.30921

- Coriddi M, Myers P, Mehrara B, et al. Management of postoperative microvascular compromise and ischemia reperfusion injury in breast reconstruction using autologous tissue transfer: retrospective review of 2103 flaps. Microsurgery. 2022;42(2):109-116. doi:10.1002/micr.30845

- Largo RD, Selber JC, Garvey PB, et al. Outcome analysis of free flap salvage in outpatients presenting with microvascular compromise. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(1):20e-27e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000003917

- Okazaki M, Asato H, Takushima A, et al. Analysis of salvage treatments following the failure of free flap transfer caused by vascular thrombosis in reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(4):1223-1232. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000254400.43453.c7