Summary Card

Definition

Infantile haemangiomas are benign vascular tumours with a distinct growth and regression pattern, classified as superficial or deep based on presentation.

Aetiology

Infantile haemangiomas are caused by the dysregulation of both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.

Clinical Features

Infantile haemangiomas present shortly after birth as flat, erythematous patches and evolve through nascent, proliferation, plateau, and involution phases.

Investigations

Infantile haemangiomas are primarily diagnosed clinically, with histology, immunohistochemistry, and imaging used to support or confirm the diagnosis in atypical cases.

Management

Most infantile haemangiomas do not require treatment, but complicated cases can be managed with medications (e.g., propranolol), laser therapy, surgical excision, embolization, or liposuction.

Complications

Complications of infantile haemangiomas can include ulcerations, airway obstruction, cosmetic disfigurement, skeletal distortion, and specific syndromes such as PHACES and LUMBAR.

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow.

Reviewer: Dr Suzanne Thomson, Educational Fellow.

Definition of Infantile Haemangioma

Infantile haemangiomas are benign vascular tumours with a distinct growth and regression pattern, classified as superficial or deep based on presentation.

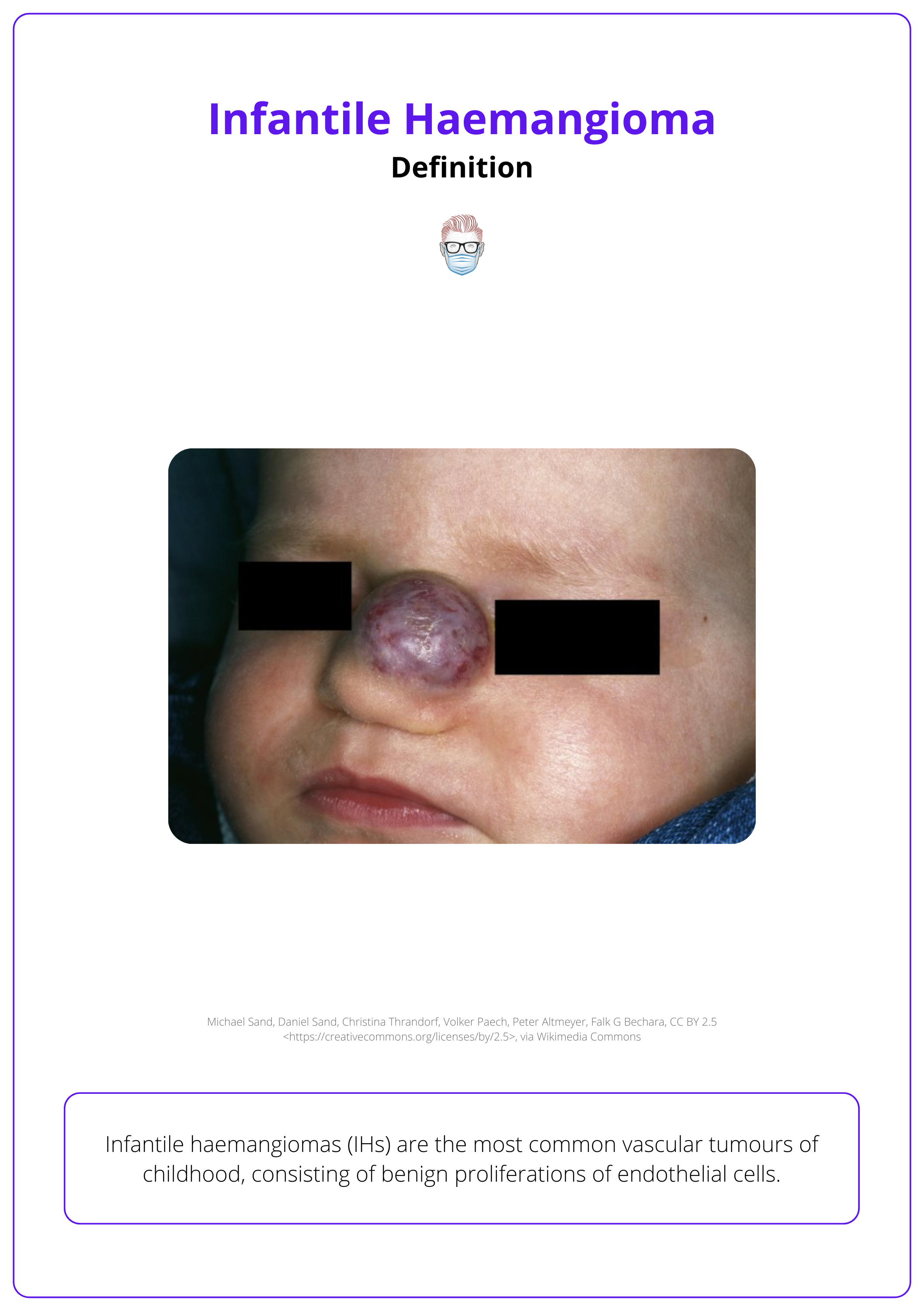

Infantile haemangiomas are the most common vascular tumours in infancy, characterized by rapid growth in the first year of life followed by spontaneous regression over several years. They are most often found on the face, scalp, chest, or back.

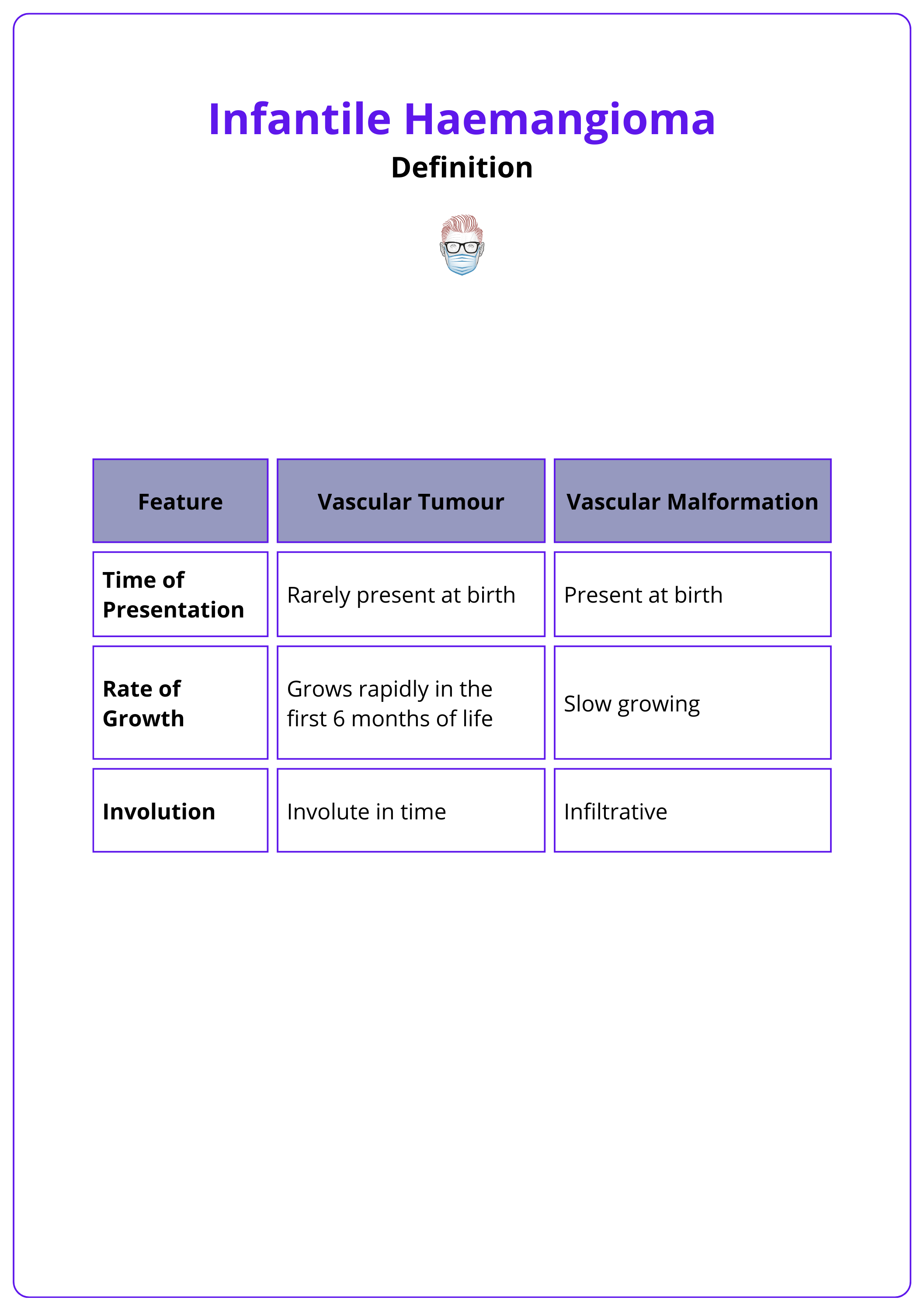

They have distinct features that set them apart from other vascular anomalies.

- Benign tumours arising from endothelial cell proliferation.

- Proliferative growth phase in the first year of life.

- Followed by slow involution over several years.

The image below illustrates an infantile haemangioma.

Infantile haemangiomas are the most common benign tumour in infancy, affecting approximately 5% of newborns (Haggstrom, 2007 & Léauté-Labrèze C, 2017).

Aetiology of Infantile Haemangioma

Infantile haemangiomas arise from the dysregulation of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, with hypoxia playing a key role in their pathogenesis.

The exact cause of infantile haemangiomas remains unclear, but theories suggest a multifactorial origin involving hypoxia, progenitor cells, and placental anomalies. Dysregulated vasculogenesis and angiogenesis are central to their development (Léauté-Labrèze C 2017, Chamli 2023).

Pathophysiology

- Hypoxia: Hypoxic stress upregulates the expression of GLUT-1 and VEGF, leading to the mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells, which express markers CD133 and CD31.

- Placental Trophoblast Theory: Stem cells from placental trophoblasts are hypothesized to contribute to haemangioma formation.

- Dysregulated Vessel Formation: Both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis are implicated in haemangioma development.

The differences between various types of vascular anomalies are illustrated below.

Risk Factors

Certain demographics, maternal factors, and birth conditions increase susceptibility (Hasbani 2022, Chamli 2023, Léauté-Labrèze C 2017).

- Demographics: Female sex (3:1 ratio) and Caucasian ethnicity.

- Birth Factors: Prematurity, low birth weight, and prenatal hypoxia.

- Maternal Factors: Older maternal age, intrauterine complications (e.g., eclampsia), and chorionic villus sampling.

- Genetic Predisposition: Family history of haemangiomas.

- Multiple Gestations: Higher incidence in twins or multiples.

Clinical Features of Infantile Haemangioma

Infantile haemangiomas present shortly after birth as flat, erythematous patches and evolve through nascent, proliferation, plateau, and involution phases. Differential diagnosis includes congenital haemangioma, pyogenic granuloma, and Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma.

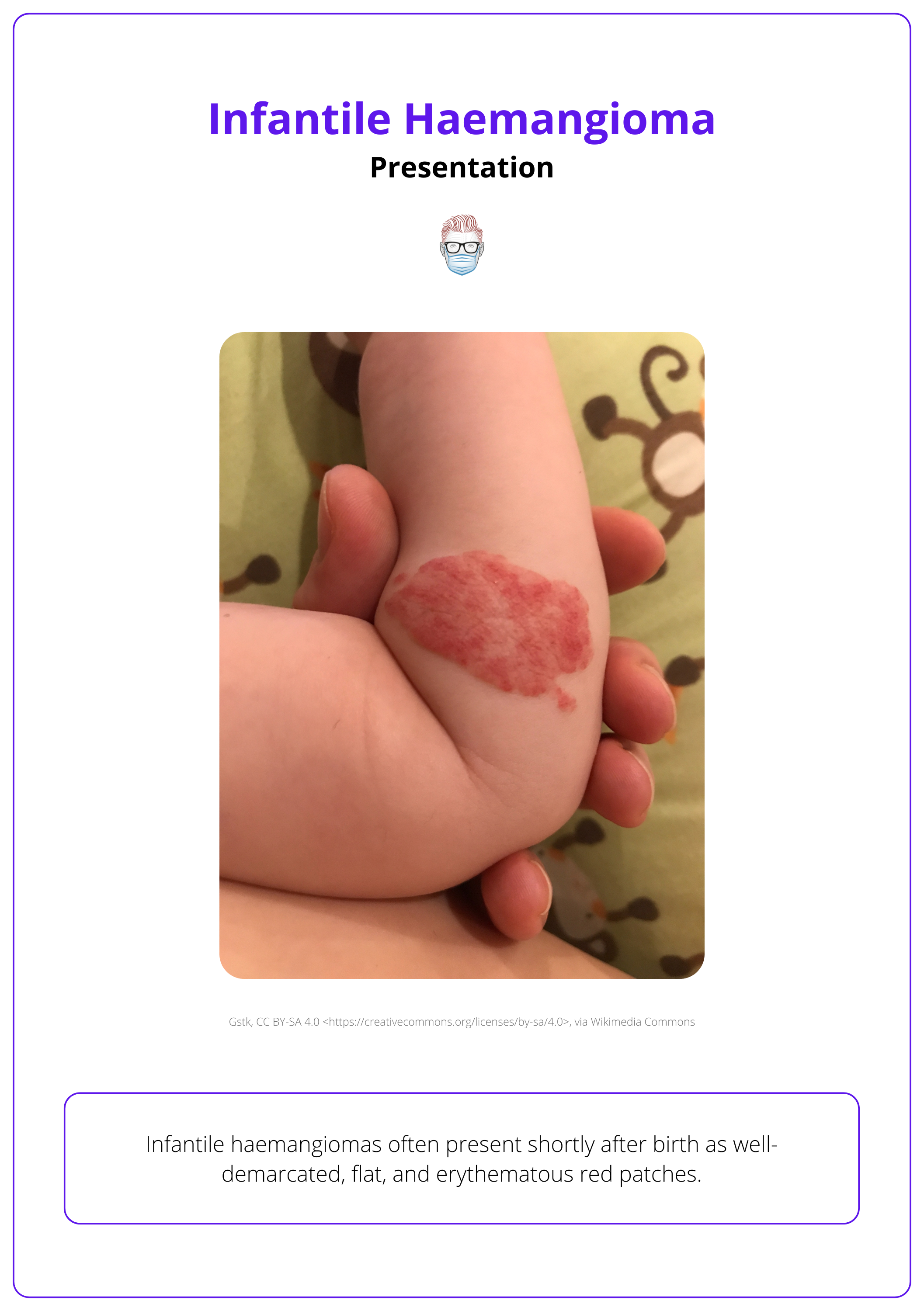

Infantile haemangiomas typically appear shortly after birth as well-demarcated, flat erythematous patches. Their unique growth phases and appearance help distinguish them from other vascular anomalies.

Appearance

The appearance of an infantile haemangioma varies based on its depth, leading to its subclassification into superficial and deep types.

- Superficial: Elevated red papules, nodules, or plaques located in the upper dermis. This is illustrated below.

- Deep: Bluish tumours with indistinct borders, typically noticeable 2–3 months after birth due to their extension into adipose tissue.

Infantile haemangiomas are typically located on the limbs, face, and trunk. Head and neck lesions align with the trigeminal nerve, while a beard-like distribution is associated with subglottic haemangiomas in 60% of cases. (Ritcher, 2012).

Evolution

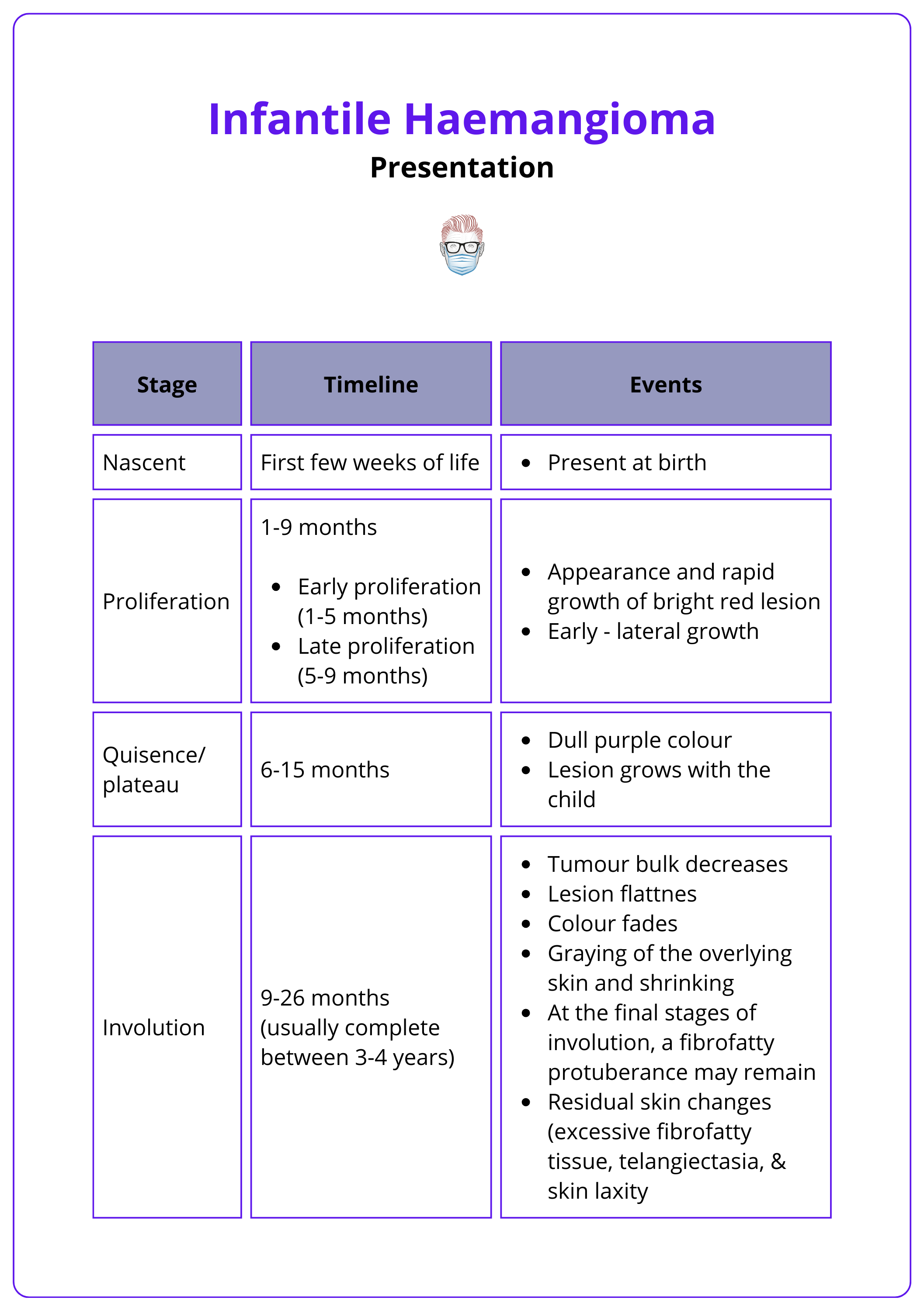

The progression of infantile haemangiomas includes four distinct stages, each defined by unique changes in size and appearance.

- Nascent Phase: Flat, erythematous patches that may resemble other birthmarks.

- Proliferation Phase: Rapid growth and vertical expansion during the first year. This may cause ischemia, necrosis, ulceration, and bleeding (Ritcher, 2012).

- Plateau Phase: Stabilization of growth.

- Involution Phase: Gradual regression over several years.

The evolution of an infantile haemangioma is illustrated in the table below.

The timing of involution is a predictor of outcome, rather than the site, number, early growth rate, or ulceration (Janis, 2023).

Associated Syndromes

Infantile haemangiomas are linked to two key syndromes characterized by developmental anomalies.

- PHACES Syndrome: Large segmental facial haemangiomas and

- Brain and Arteries: Posterior fossa malformations, arterial anomalies.

- Heart and Eyes: Cardiac anomalies, eye anomalies.

- Skin: Sternal or umbilical raphe.

- LUMBAR Syndrome: Lumbosacral haemangiomas and

- Spine and Organs: Myelopathy, renal anomalies.

- Bones and Vessels: Bony deformities, anorectal or arterial anomalies.

- Urogenital System: Urogenital anomalies.

Differential Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of infantile haemangiomas requires differentiation from similar vascular anomalies.

- Congenital Haemangioma (GLUT1-negative)

- RICH: Fully formed at birth, regresses quickly, may cause cardiac failure.

- PICH: Partial regression with unpredictable resolution.

- NICH: Persistent lesions requiring cosmetic treatment.

- Pyogenic Granuloma

- Vascular papules following trauma, commonly on the face and neck.

- Prone to bleeding; histology shows capillary proliferation.

- Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma

- Aggressive tumours causing thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy.

- Treated with vincristine.

Investigations for Infantile Haemangioma

Infantile haemangiomas are primarily diagnosed clinically, with histology, immunohistochemistry, and imaging used to support or confirm the diagnosis in atypical cases.

The diagnosis of infantile haemangioma is largely clinical, based on characteristic features observed during examination. In certain cases, additional investigations—such as histology, immunohistochemistry, or imaging—are employed to confirm the diagnosis or evaluate complex lesions.

Histology

Histological examination highlights characteristic features of infantile haemangiomas.

- Multinodular pattern fed by a single arteriole.

- Nodules composed of hyperplastic endothelial cells, pericytes, and prominent basement membranes.

- Proliferative Phase: Increased vascular lumens with hyperplastic endothelial cells.

- Involution Phase: Dilated vascular lumens, flattened endothelial cells, and increased fibrosis contributing to lobular architecture.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC is used to confirm the diagnosis by identifying markers unique to infantile haemangiomas.

- GLUT1: Differentiates IH (GLUT1-positive) from congenital haemangiomas (GLUT1-negative).

- Other markers: CD31, von Willebrand factor, urokinase, LYVE-1, merosin, and antigen Lewis Y (Chamli, 2023 & Léauté-Labrèze C, 2017)

Imaging

Imaging is reserved for atypical presentations or deep haemangiomas to assess lesion extent.

- Ultrasonography: Useful for superficial haemangiomas, showing a high-flow vascular pattern.

- CT and MRI: Evaluate deep or complex haemangiomas and their anatomical relationships.

A CT image of infantile hemangioma can be seen below.

Special Investigations

In specific cases, targeted investigations are required.

- Echocardiography: For large or multifocal IHs, PHACE syndrome, or lumbosacral IHs.

- Coagulation Screening: Rule out disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in multifocal intrahepatic IHs by checking platelets, fibrinogen, and D-dimers.

- TSH Screening: Assess for secondary hypothyroidism in large or multifocal IHs (>5 sites) (Torres 2015).

GLUT1 is a definitive marker that differentiates infantile haemangiomas (GLUT1-positive) from congenital haemangiomas (GLUT1-negative).

Management of Infantile Haemangioma

Most infantile haemangiomas regress without intervention, but complicated cases may require propranolol, laser therapy, surgery, or other targeted treatments.

The majority of infantile haemangiomas resolve without intervention. However, 10–15% develop complications like ulceration, bleeding, airway obstruction, or permanent disfigurement, requiring targeted treatment (Léauté-Labrèze C, 2017) For these cases, a multidisciplinary approach ensures the best outcome.

Medical Management

Beta-blockers are the cornerstone of treatment for complicated haemangiomas.

- Propranolol: First-line therapy for complicated IHs (2 mg/kg/day for ~6 months). Side effects include bradycardia, hypotension, bronchospasm, and hypoglycemia, necessitating close monitoring (Léauté-Labrèze C, 2017).

- Timolol: A topical beta-blocker for small, superficial, and uncomplicated haemangiomas.

Propranolol, a nonselective β-blocker, was discovered serendipitously to regress haemangiomas in newborns treated for cardiac issues, possibly through regulating vascular growth factors and cytokines. (Ritcher, 2012).

Flash Pulse Dye Laser Therapy

- Addresses both active and residual IH-related lesions.

- Treats residual erythema and telangiectasias post-involution.

- Promotes healing in ulcerative lesions during the proliferative phase (Ritcher, 2012)

Surgical Intervention

Surgical excision is considered for severe complications or residual deformities in infantile haemangiomas. More specifically,

- Localized Lesions or Fibrofatty Remnants: Post-involution changes requiring removal such as fibrofatty tissue, telangiectasia, or skin laxity.

- Persistent Visual Obstruction: Risks amblyopia or other vision issues.

- Nasolaryngeal Obstruction: Causes airway compromise and requires aggressive treatment.

- Auditory Canal Obstruction: Leads to conductive hearing loss.

- Painful Ulceration: Non-healing lesions causing significant discomfort.

- Contraindications to Propranolol: asthma, congenital heart block.

Other Interventions

- Embolization: Reserved for life-threatening haemangiomas unresponsive to medical management, particularly visceral IHs.

- Liposuction: Used to address subcutaneous tissue overgrowth associated with IH (Couto, 2015).

Complications of Infantile Haemangiomas

Infantile haemangiomas can lead to complications such as ulceration, airway obstruction, skeletal distortion, and specific syndromes like PHACES and LUMBAR.

The severity of complications from infantile haemangiomas depends on factors like the patient’s age and the size, location, and growth rate of the haemangioma. Certain cases require intervention due to functional or cosmetic concerns (Chamli, 2023 & Léauté-Labrèze C, 2017).

- Ulceration: High-risk areas are anogenital region, lower lip, axilla, and neck.

- Ophthalmologic Issues: Amblyopia, astigmatism, myopia, retrobulbar involvement, tear duct obstruction.

- Airway Obstruction: Nasal, subglottic, and laryngeal regions.

- Feeding Difficulties: Perioral or lip haemangiomas.

- Cosmetic Disfigurement: Large facial haemangiomas affecting nasal tip, ears, or perioral regions.

- Visceral Haemangiomatosis: Liver or GI involvement, >5 skin lesions.

- High-Output Heart Failure: Large visceral or hepatic haemangiomas.

- Skeletal Distortion: Bone deformation from haemangioma pressure.

- Hypothyroidism: Due to iodothyronine deiodinase expression in diffuse or multifocal haemangiomas.

- Emotional/Psychological Distress: Visible deformities.

Conclusion

1. Overview of Infantile Hemangiomas: Outlined the prevalence and nature of infantile hemangiomas as common vascular tumors in children.

2. Causes and Risk Factors: Discussed the etiology involving dysregulation of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, with risk factors.

3. Classification and Types: Described the classification into superficial and deep types, detailing their appearance and development stages.

4. Clinical Presentation: Covered the typical presentation of hemangiomas and the significance of growth patterns and complications.

5. Diagnostic Approaches: Reviewed the diagnostic process, incorporating clinical evaluation, histology, immunohistochemistry, and various imaging techniques.

6. Treatment Modalities: Explained management strategies for complicated cases, including pharmacological treatments like propranolol, laser therapy, surgical options, and emerging techniques like embolization and liposuction.

7. Complications and Associated Disorders: Addressed potential complications and differentiated infantile hemangiomas from similar conditions.

Further Reading

- Richter GT, Friedman AB. haemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678. Epub 2012 May 7. PMID: 22611412; PMCID: PMC3352592.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB, Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe haemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jun 12;358(24):2649-51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708819. PMID: 18550886.

- haemangioma Investigator Group. Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Horii KA, Lucky AW, Mancini AJ, Metry DW, Newell B, Nopper AJ, Frieden IJ. Prospective study of infantile haemangiomas: demographic, prenatal, and perinatal characteristics. J Pediatr. 2007 Mar;150(3):291-4.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017 Jul 01;390(10089):85-94

- Chamli A, Aggarwal P, Jamil RT, et al. haemangioma. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538232/

- ThePlasticsFella. Classification of Vascular Anomalies, Malformations & Tumours. May 2022. Accessed on 31 August 2024

- Hasbani DJ, Hamie L. Infantile haemangiomas. Dermatol Clin. 2022 Oct;40(4):383-392. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2022.06.004. Epub 2022 Sep 16. PMID: 36243426.

- Couto JA, Maclellan RA, Greene AK. Management of Vascular Anomalies and Related Conditions Using Suction-Assisted Tissue Removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Oct;136(4):511e-514e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001558. PMID: 26397270.

- Janis, J.E. ed., 2023. Essentials of aesthetic surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag.

- Torres E, Rosa J, Leaute-Labreze C, Soares-de-Almeida L. Multifocal infantile haemangioma: a diagnostic challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016 Jun 17;2016:bcr2016214827. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-214827. PMID: 27317759; PMCID: PMC4932334.