Summary Card

Definition

The commonest craniofacial abnormality is characterised by a spectrum of underdeveloped congenital facial features.

Clinical Picture

A variable phenotype of ear, bone, and muscle hypoplasia of differing severity. It is linked to cleft palate, facial nerve palsy, & macrostomia.

Classification

Multiple systems exist to overcome clinical heterogeneity. This includes OMENS, Pruzansky (Mandible), and Meurman (Ear).

Management

A multi-disciplinary team to correct ocular, mandibular, ear, facial nerve, and soft tissue issues over staged treatments.

Definition of Hemifacial Microsomia

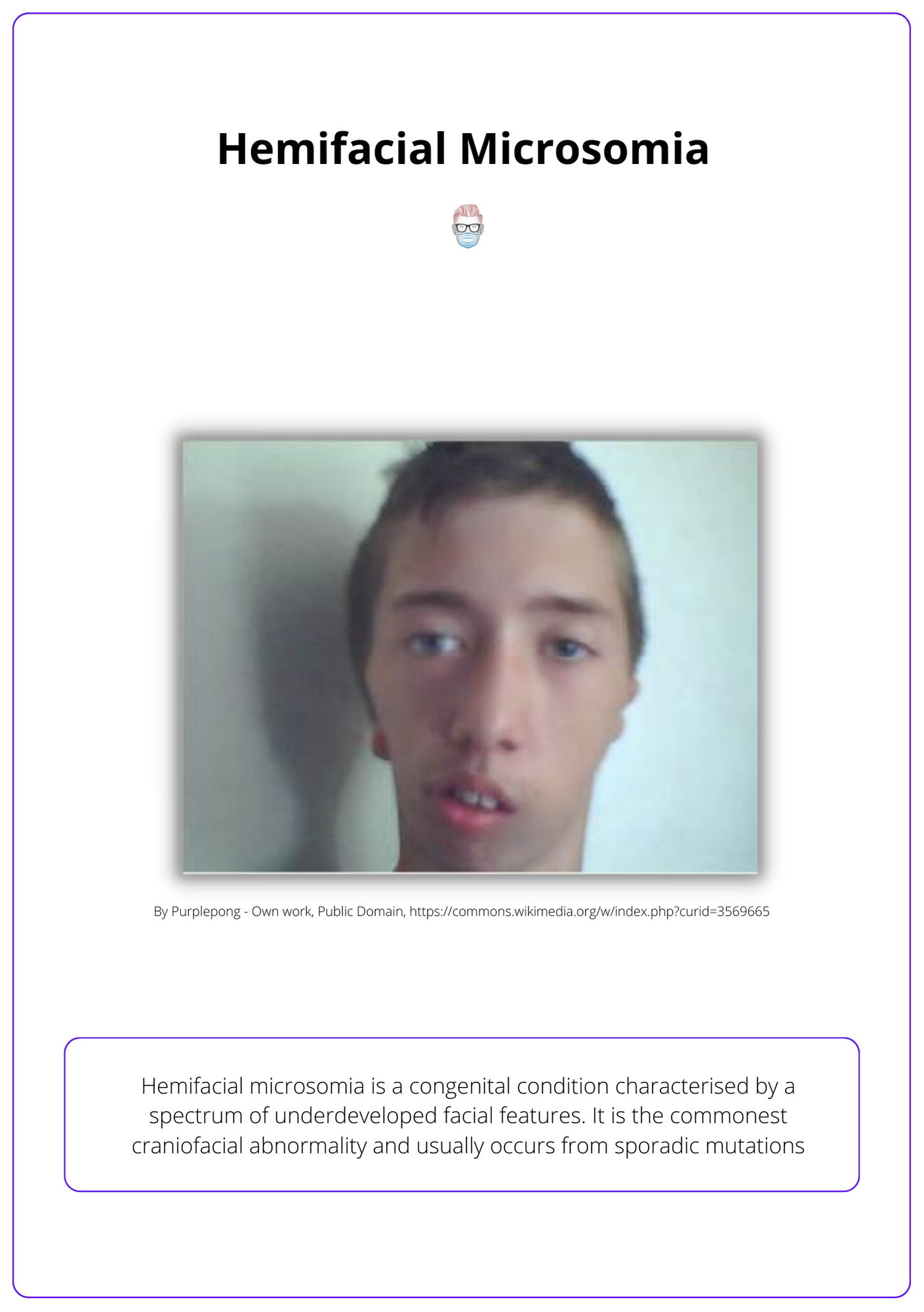

Hemifacial microsomia is a congenital condition marked by a range of underdeveloped facial features, making it the most common craniofacial abnormality.

Hemifacial microsomia is a congenital condition characterised by a spectrum of underdeveloped facial features. It is the most common craniofacial abnormality (Grabb, 1965) and usually occurs from sporadic mutations (Burck, 1983) that affect the first and second branchial arches.

The image below illustrates hemifacial microsomia.

Other names for hemifacial microsomia include First and Second Brachial Arch Syndrome, Otomandibular Dysostosis, Craniofacial Microsomia, or the oculoauriculovertebral spectrum. It correlates with Tessier Craniofacial Cleft 7.

Clinical Features of Hemifacial Microsomia

Hemifacial microsomia is a spectrum of clinical pathology that involves the ear, bone, and muscle. Each patient has a variable phenotypic appearance.

Hemifacial microsomia is a clinical diagnosis. It is usually a unilateral condition but can be bilaterally asymmetric. There is a variable phenotype, which means the clinical features are part of a spectrum of severity.

"Classic" Clinical Features

- Ear underdevelopment: Microtia, anotia, atresia.

- Hypoplasia of the bone: Mandible, zygoma, maxilla, temporal bone.

- Muscle underdevelopment: Mastication, palatal, tongue.

Associated pathologies

- Cleft Palate: ~35% incidence in hemifacial microsomia (Sokol, 1978).

- Facial Nerve Dysfunction: ~22% incidence8 ± absent parotid gland.

- Macrostomia: ~23% incidence in hemifacial microsomia (Fan, 2005).

Classification of Hemifacial Microsomia

The phenotypic variability makes it difficult to classify hemifacial microsomia. Options include OMENS, Pruzansky for Mandible, and Meurman for Ear.

Multiple classification systems for hemifacial microsomia exist. This is to overcome the heterogeneity of clinical appearances from this condition.

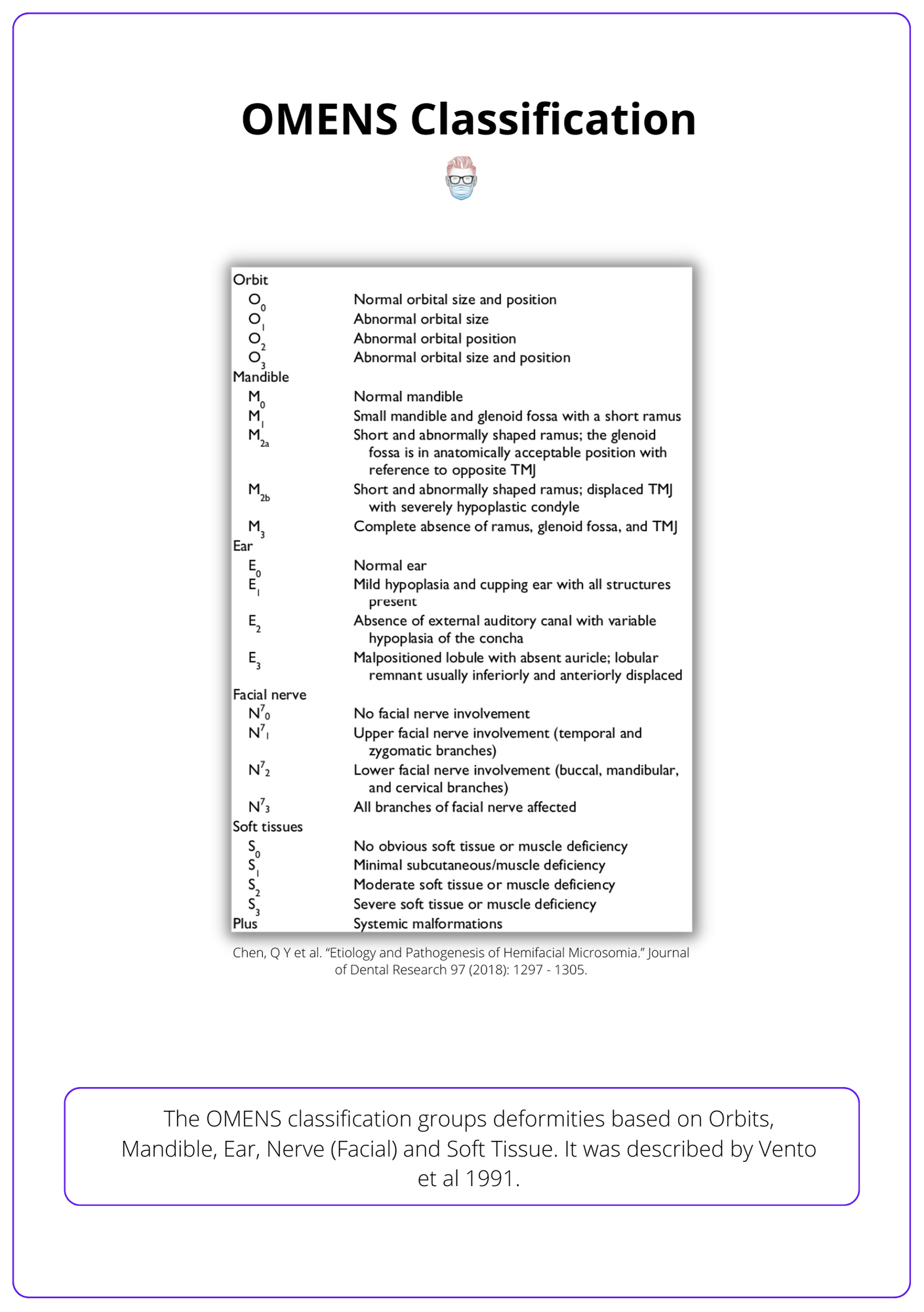

OMENS Classification for Hemifacial Microsomia

This classifies deformities based on Orbits, Mandible, Ear, Nerve (Facial) and Soft Tissue (Vento, 1991). Unlike other classifications, this encompasses the clinical spectrum of the condition.

The image below illustrates the OMENS Classification.

Pruzansky Classification of the Mandible

The Pruzansky classification assesses the degree of mandibular involvement in hemifacial microsomia. Most commonly, there is an asymmetric mandible with only unilateral involvement.

- I: Mild ramus hypoplasia; the body is minimally affected.

- IIa: Ramus & condyle hypoplasia, the glenoid-condyle surface is normal.

- IIb: Type IIa and a non-articulating TMJ.

- III: Thin or absent ramus and no TMJ.

The image below illustrates the Pruzansky classification.

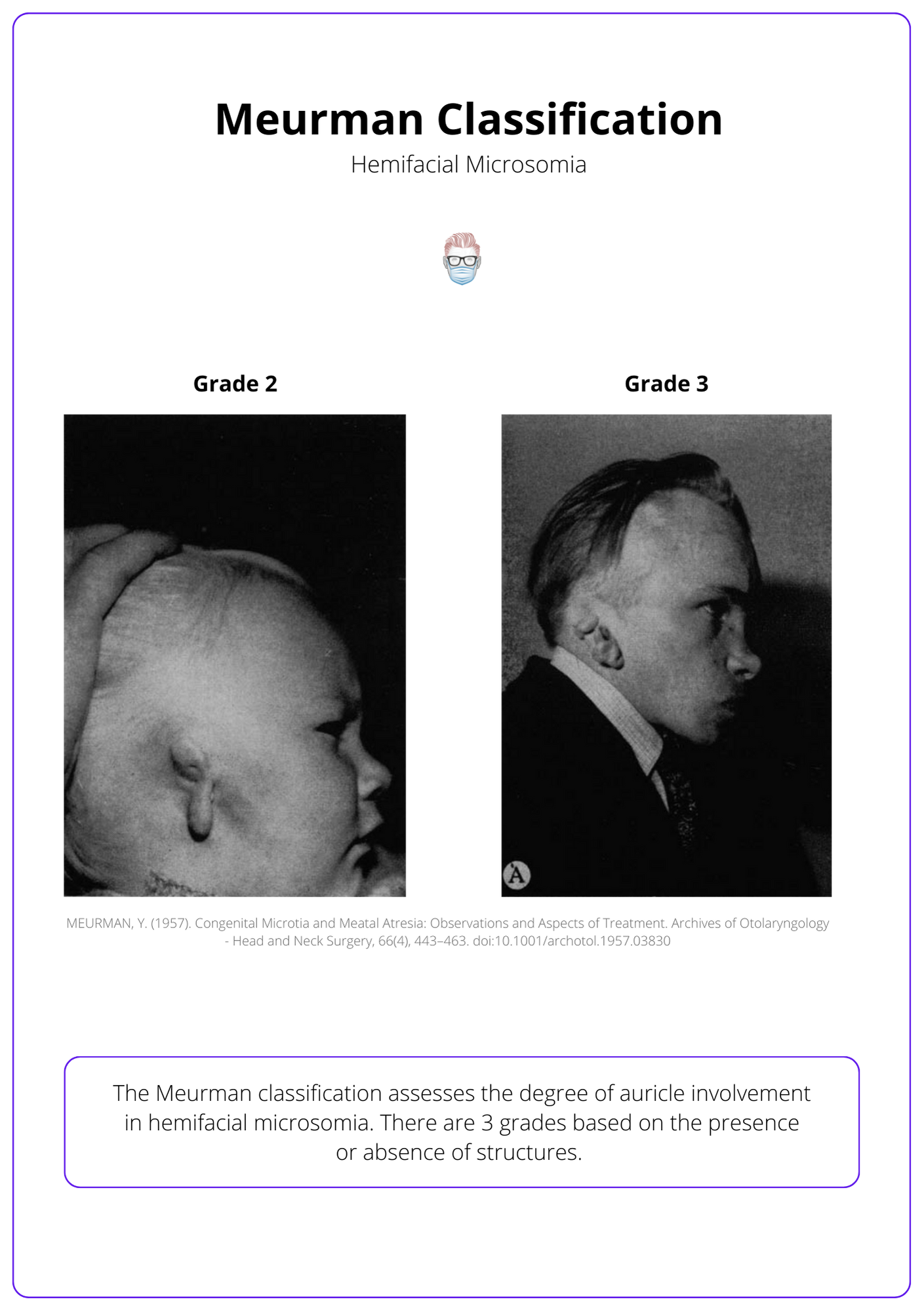

Meurman Classification of the Ear

The Meurman classification assesses the degree of auricle involvement in hemifacial microsomia. There are 3 grades based on the presence or absence of structures.

- I: Small ear with all structures present.

- II: cartilage and skin remnant, atresia of the external meatus

- III: total or near-total absence of the ear.

The image below illustrates the Meurman classification.

Management of Hemifacial Microsomia

The treatment should be individualised to the patient. Key aspects include oral competence, hearing, dentition, mandibular reconstruction, and facial palsy treatment, if present.

There is no standardised treatment algorithm for hemifacial microsomia. This is primarily due to the phenotypic variation of patients. Current evidence-based practice promotes individualised patient care.

Minor Interventions

- Skin Tags: remove skin tags at an appropriate age. Pre-auricular skin tags with cartilage remnants may be near the facial nerve.

- Deafness: fit hearing aids as an infant to ensure no speech delay.

- Teeth: orthodontic treatment as a child and early adolescents.

Microtia

If microtia is present, ear reconstruction with autologous material should be delayed until the patient is age-appropriate, between 7 and 10 years, depending on the technique used (Brent, 1992 & Nagata, 1994).

Mandibular Hypoplasia

There is no standardised algorithm for the timing of surgical management of mandibular hypoplasia. Traditionally, surgeons have waited until skeletal maturity to correct malocclusion with orthognathic procedures (Meazzini, 2012 & Schreuder, 2007).

- In severe cases, early mandibular distraction can be considered to allow for appropriate bone stock development (Wan, 2011).

- In Pruzansky III, mandibular reconstruction may require a costochondral rib graft, bone grafts, and alloplastic implants.

Facial Paralysis

Management of these patients should be at centres that specialise in facial reanimation surgery. Ocular protection from corneal desiccation and ulceration is a priority.

Conclusion

1. Understanding Hemifacial Microsomia: You’ve reviewed Hemifacial Microsomia, recognizing it as the most common craniofacial abnormality characterized by a spectrum of underdeveloped facial features.

2. Clinical Features: You are aware of the variable clinical presentation of Hemifacial Microsomia, including ear, bone, and muscle hypoplasia, and its association with conditions such as cleft palate, facial nerve palsy, and macrostomia.

3. Classification Systems: You have learned about various classification systems that describe the severity and specifics of Hemifacial Microsomia.

4. Management: You've understood the multidisciplinary approach for managing Hemifacial Microsomia, focusing on corrective and reconstructive procedures for ocular, mandibular, ear, facial nerve, and soft tissue abnormalities.

5. Multi-stage Treatments: You are prepared to guide patients through the potentially complex, staged treatments needed to address both functional and aesthetic concerns associated with Hemifacial Microsomia.

References

- Keogh IJ, Troulis MJ, Monroy AA, Eavey RD, Kaban LB. Isolated Microtia as a Marker for Unsuspected Hemifacial Microsomia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. October 2007:997. doi:10.1001/archotol.133.10.997

- Fawzy HAAR, Ghareeb F, Farghaly A-S, Al Barah A, El Sheikh Y. Patterns and management of congenital nasal clefts. Menoufia Med J. 2015:99. doi:10.4103/1110-2098.155960

- Grabb W. The first and second branchial arch syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965;36(5):485-508. doi:10.1097/00006534-196511000-00001

- Burck U. Genetic aspects of hemifacial microsomia. Hum Genet. 1983;64(3):291-296. doi:10.1007/bf00279415

- STARK R, SAUNDERS D. The first branchial syndrome. The oral-mandibular-auricular syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;29:229-239. doi:10.1097/00006534-196203000-00001

- Poswillo D. The pathogenesis of the first and second branchial arch syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;35(3):302-328. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(73)90070-4

- Sokol AB. Velopharyngeal insufficiency in hemifacial microsomia. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. June 1978:344. doi:10.1016/s0022-3468(78)80416-3

- Carvalho G, Song C, Vargervik K, Lalwani A. Auditory and facial nerve dysfunction in patients with hemifacial microsomia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(2):209-212. doi:10.1001/archotol.125.2.209

- Fan W, Mulliken J, Padwa B. An association between hemifacial microsomia and facial clefting. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(3):330-334. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2004.10.006

- Vento A, LaBrie R, Mulliken J. The O.M.E.N.S. classification of hemifacial microsomia. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1991;28(1):68-76; discussion 77. doi:10.1597/1545-1569_1991_028_0068_tomens_2.3.co_2

- Brent B. Auricular repair with autogenous rib cartilage grafts: two decades of experience with 600 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90(3):355-374; discussion 375-6.

- Nagata S. Modification of the stages in total reconstruction of the auricle: Part IV. Ear elevation for the constructed auricle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(2):254-266; discussion 267-8.

- Meazzini M, Mazzoleni F, Bozzetti A, Brusati R. Comparison of mandibular vertical growth in hemifacial microsomia patients treated with early distraction or not treated: follow up till the completion of growth. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40(2):105-111. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2011.03.004

- Schreuder W, Jansma J, Bierman M, Vissink A. Distraction osteogenesis versus bilateral sagittal split osteotomy for advancement of the retrognathic mandible: a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36(2):103-110. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2006.12.002

- Wan D, Taub P, Allam K, et al. Distraction osteogenesis of costocartilaginous rib grafts and treatment algorithm for severely hypoplastic mandibles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(5):2005-2013. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820cf4d6