Summary Card

Overview

Facial nerve palsy is characterized by weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles, affecting not only motor control but also sensory and autonomic functions of the face.

Anatomy of the Facial Nerve

The facial nerve originates in the pons and travels through the internal auditory and facial canals to exit via the stylomastoid foramen, where it branches into five divisions that control facial expression, taste, and gland secretion.

Causes

Causes are categorized as intracranial (e.g., stroke, tumors), intratemporal (e.g., Bell’s palsy, infections), or extratemporal (e.g., trauma, neoplasms).

Clinical Assessment

Assessment of the facial nerve includes a detailed history, a targeted focal and systemic examination, and investigations, including blood tests, electrophysiological studies such as EMG, and imaging.

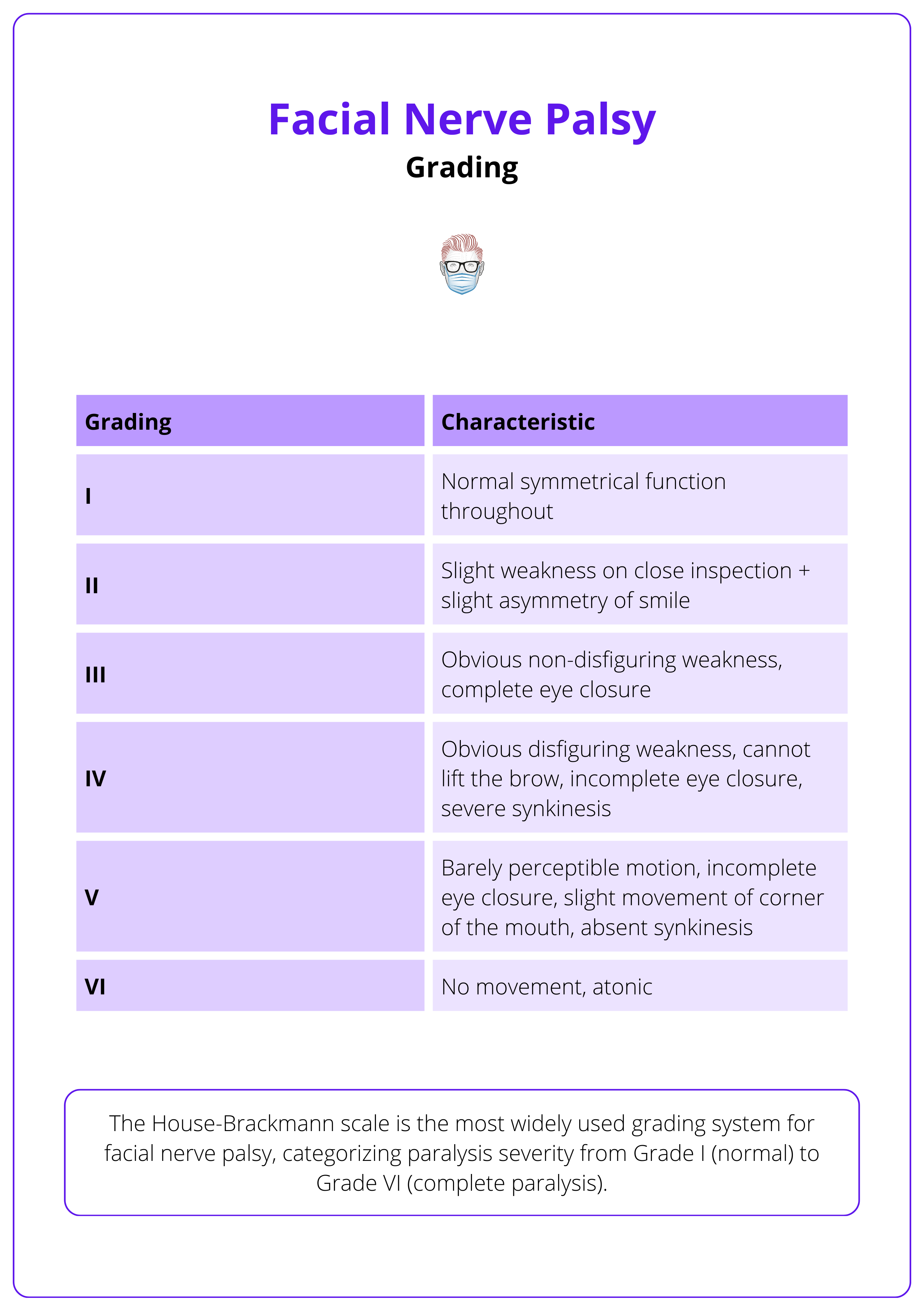

Grading

Facial nerve palsy is most commonly graded using the House-Brackmann scale, but additional grading systems are also used, particularly for reconstructive and functional assessments.

Management

Management of facial nerve palsy includes non-operative treatments, static procedures, and dynamic reanimation techniques, all tailored to the aetiology, degree of nerve damage, and duration of paralysis.

Complications

Facial nerve palsy can lead to a range of complications that impact vision, facial symmetry, and overall function. Prognosis varies based on factors such as severity, patient age, and treatment response.

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Kurt Lee Chircop Educational Fellows.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Facial Nerve Palsy

Facial nerve palsy is characterized by weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles, affecting not only motor control but also sensory and autonomic functions of the face.

Facial nerve palsy is a condition characterized by weakness or paralysis of the muscles responsible for facial expression. It presents with a wide range of effects, from motor deficits that impair essential functions such as smiling and blinking to sensory and autonomic disturbances affecting tear and saliva production.

The image below shows right-sided facial palsy.

A critical component of understanding facial nerve palsy is distinguishing between central and peripheral lesions. This differentiation not only aids in diagnosis but also directs appropriate treatment strategies.

Anatomy of the Facial Nerve

The facial nerve originates in the pons, travels through the internal auditory and facial canals to exit via the stylomastoid foramen, where it branches into five divisions that control facial expression, taste, and gland secretion.

Facial nerve anatomy begins its journey in the brainstem, specifically in the pons, and follows a complex path before reaching the face. It travels through several key regions.

- Intracranial Segment: Originates in the pons.

- Intratemporal Segment: Passes through the internal auditory canal and the facial canal within the temporal bone.

- Extratemporal Segment: Exits the skull via the stylomastoid foramen, enters the parotid gland, and divides into its five terminal branches.

Facial nerve anatomy is illustrated below.

These terminal branches are the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical divisions.

The nerve has three main functional components.

- Motor: Controls the muscles for facial expression.

- Sensory: Provides taste sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and tactile sensation to the skin of the concha.

- Parasympathetic: Supplies secretomotor fibers to the lacrimal, submandibular, and sublingual glands.

Causes of Facial Nerve Palsy

Causes are categorized as intracranial (e.g., stroke, tumors), intratemporal (e.g., Bell’s palsy, infections), or extratemporal (e.g., trauma, neoplasms).

Facial nerve palsy covers a wide range of conditions and is traditionally categorized into upper and lower motor neuron lesions. Lower motor neuron lesions include Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome, while upper motor neuron lesions encompass conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, subdural hemorrhage, and intracranial neoplasia.

Bell's Palsy

Bell’s palsy accounts for the majority of acute unilateral facial nerve palsy cases, with over 90% recovering fully (Flifel, 2020). Key points in relation to Bell's Palsy include,

- Idiopathic lower motor neuron disorder typically after a viral prodrome.

- Complete unilateral facial paralysis, recurrence in 10%, recovery up to one year (with 13% incomplete) (Walker, 2023).

Other Causes

Other Causes of facial nerve palsy can be classified according to the location where the pathology or injury has occurred (Spencer, 2016).

Intracranial Causes

- Vascular: Stroke, TIA, aneurysms.

- Neoplasms: Primary or secondary intracranial tumors.

- Trauma: Brainstem or intracranial injuries.

- Congenital: Conditions like Möbius syndrome or Goldenhar syndrome.

Intratemporal Causes

- Idiopathic: Bell's Palsy.

- Infections: Viral (herpes simplex, varicella-zoster); bacterial (otitis media), Lyme Disease (Hohman, 2023).

- Trauma: Temporal bone fractures.

- Neoplasms: Acoustic neuroma compressing CN VII.

Extratemporal Causes

- Neoplastic: Parotid gland malignancies, facial nerve tumors.

- Trauma: Penetrating trauma, birth trauma.

- Iatrogenic: Parotid, Acoustic Neuroma surgery

- Congenital: Hemifacial microsomia.

Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome is a rare idiopathic condition marked by non-inflammatory facial edema, congenital tongue fissures (lingua plicata), and facial palsy (Fagan, 2014).

Clinical Assessment of Facial Nerve Palsy

Assessment of the facial nerve includes a detailed history, a targeted focal and systemic examination, and investigations, including blood tests, electrophysiological studies such as EMG, and imaging.

Clinical assessment of facial nerve palsy relies on history, examination, and distinguishing central from peripheral causes using features such as symmetry, muscle movements, and special sensory changes.

History

A thorough history is essential to determine the underlying cause, severity, and progression of facial nerve palsy. Once aetiology is established, the next step is to ascertain the time elapsed since onset, as this will directly affect the surgical strategy employed.

Onset and Progression

- Sudden onset (e.g., Bell’s palsy) versus gradual progression (e.g., tumors).

- Evaluate the duration, rate of worsening, and any fluctuations in severity.

- Any head or neck trauma that could suggest a temporal bone fracture or iatrogenic injury.

Associated Symptoms

- Otological: Otalgia (ear pain), otorrhoea (ear discharge), hearing loss, ear fullness, tinnitus, and dizziness, which may indicate conditions like otitis externa, otitis media, or temporal bone pathology.

- Vesicular Eruptions/Rash: Suggestive of Ramsay Hunt syndrome or herpes zoster.

- Brow Ptosis: Can obstruct vision and cause chronic eye irritation.

- Systemic Symptoms: May point to underlying conditions such as sarcoidosis or Lyme disease.

Examination

The goal of examination is to determine the location of the facial nerve palsy and potential aetiology. This should be done in a systematic fashion to assess both focal deficits and systemic signs.

Terminal Branches

Begin by evaluating each branch of the facial nerve (temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical).

- Temporal: Test eyebrow elevation, forehead wrinkling degree of brow ptosis. This branch innervates the frontalis, orbicularis oculi, and corrugator supercilii.

- Zygomatic: Evaluate complete eye closure, ectropion, Bell’s phenomenon and Snap Test. This branch controls the lower orbicularis oculi, essential for corneal protection.

- Buccal: Ask the patient to smile and puff out their cheeks. Innervates the buccinator and orbicularis oris; dysfunction allows air to escape from the affected side (Masterson, 2015).

- Mandibular Branch: Assess for commissure droop or philtrum deviation, and observe lip movement during smiling. This branch innervates the depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris; dysfunction results in a flattened nasolabial fold and asymmetry.

- Cervical: Check neck and lower facial expressions. The cervical branch innervates the platysma, which tenses neck skin and aids lower facial movement.

The below table breaks down the clinical examination of facial nerve palsy.

Using the "Look & Move ± Feel" approach, differentiate between UMN lesions (forehead sparing due to bilateral cortical innervation) and LMN lesions (causing complete facial paralysis).

Specific Competence Examinations

- Oral Competence: Facial weakness can impair speech (due to lower lip depressor dysfunction), complicate eating/drinking (with risk of food spillage in bilateral palsy), increase dental caries (from reduced saliva), and alter taste sensation (from chorda tympani involvement) (Pineckwitz, 2022).

- Ocular Competence: Denervation of the orbicularis oculi can lead to dryness, irritation, excessive tearing, exposure keratitis, corneal ulceration/infections, and long-term vision risk (Crawford, 2020).

- Otologic Evaluation: Perform otoscopy to assess for ear pain, discharge, hearing loss, tinnitus (suggestive of infection), or vesicular eruptions (indicative of Ramsay Hunt syndrome).

- Airway Competence: Assess airway patency and protective reflexes, and perform Cottle's Maneuver—which involves gently pulling the cheek laterally to widen the nasal valve—to specifically evaluate for nasal valve collapse and confirm adequate nasal airflow.

These examinations are explained in the video below.

Sensory Testing

- Taste Sensation: Apply various taste stimuli to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue to evaluate chorda tympani function; decreased or altered taste indicates its involvement.

- Hearing and Hyperacusis: Assess for sensitivity to loud sounds and check the stapedius reflex.

- Lacrimation: Use Schirmer’s test to measure tear production and assess greater superficial petrosal nerve involvement.

- Other Cranial Nerves: Evaluate CN V (facial sensation) and CN VIII (hearing) to detect additional deficits that may aid in diagnosis.

Bilateral facial nerve palsy is rare (~2% of cases); consider Lyme disease, Guillain-Barré, diabetes, sarcoidosis, and neurological causes like Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, or pseudobulbar/bulbar palsy.

Investigations

A comprehensive workup — including blood tests, special functional assessments, and imaging studies — is essential for determining the underlying cause of facial nerve palsy.

Blood Tests

- Full Blood Count (FBC): Detects infections or hematologic abnormalities.

- Urea & Electrolytes (U&E): Evaluates metabolic causes.

- C-reactive Protein (CRP): Serves as an inflammatory marker.

- Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) Antibody Titers: Elevated in Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

- Borrelia Burgdorferi IgG/IgM: Indicates Lyme disease.

Special Tests

- Audiogram: Assesses hearing loss, helping to differentiate Bell’s palsy from cerebellopontine angle tumors.

- Nerve Excitability Test (NET): Measures the minimal stimulus required for facial muscle contraction; a side-to-side difference >3.0 mA is abnormal.

- Maximal Stimulation Test (MST): Evaluates the muscle response to maximal stimulus and often becomes positive earlier than NET in nerve injuries.

- Electroneurography (ENoG): Compares muscle action potentials between affected and normal sides; >75% degeneration indicates a poor prognosis and guides early surgical planning.

- Electromyography (EMG): Detects fibrillation potentials after 14–21 days, useful for late prognostic evaluation in cases of total paralysis.

Imaging

- CT Scan: Indicated for suspected necrotizing otitis externa, middle ear infections, head trauma (to assess temporal bone fractures), or malignancy evaluation.

- MRI Scan: Used for intratemporal and intracranial pathology, particularly when suspecting facial nerve compression (e.g., at the cerebellopontine angle) or enhancement around the geniculate ganglion.

Always rule out stroke and other serious underlying conditions when evaluating facial nerve palsy. In Bell's palsy, brain MRI should be negative.

Grading of Facial Nerve Palsy

Facial nerve palsy is most commonly graded using the House-Brackmann scale, but additional grading systems are also used, particularly for reconstructive and functional assessments.

Facial nerve palsy is evaluated using standardized grading systems that help quantify severity, track recovery, and guide treatment decisions. The most common is the House-Brackmann grading system.

House-Brackmann Grading System

The H-B scale is the most widely used system, categorizing facial function from Grade I (normal) to Grade VI (total paralysis) (Samsudin, 2017). Its simplicity makes it popular for clinical use, though it may lack granularity when monitoring subtle, regional changes.

The gradings and their features are shown in the table below.

The key difference between Grades III and IV is eye closure — Grade III allows complete closure, whereas Grade IV does not.

Other Grading Systems

Other facial nerve palsy reading systems also exist and may be more useful to assess for reconstruction (Fagan, 2014).

Sunnybrook Facial Grading System

The Sunnybrook system uses a composite score (0–100) to assess regional function, including synkinesis, making it highly reproducible and sensitive for longitudinal monitoring and research. It evaluates three key components,

- Resting Symmetry: symmetry of the eye, cheek, and mouth.

- Voluntary Movement: forehead wrinkling, gentle eye closure, and an open-mouth smile.

- Synkinesis: degree of involuntary muscle movements during voluntary actions.

FaCE (Facial Clinimetric Evaluation) Scale

A 51-item assessment tool used to measure patient-reported outcomes. This scale is particularly valuable in reconstructive and rehabilitation settings where patient feedback on functional outcomes is crucial. It comprises of:

- 7 Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Items: Quantify subjective measures of facial function.

- 44 Likert Scale Items: Rated from 1 (worst) to 5 (best), they assess the patient’s perception of facial impairment and disability.

Management of Facial Nerve Palsy

Management of facial nerve palsy includes non-operative treatments (eye protection, physiotherapy, and monitoring), static procedures for symmetry, and dynamic reanimation techniques to restore movement, all tailored to the aetiology, degree of nerve damage, and duration of paralysis.

Management strategies for facial nerve palsy are guided by the underlying aetiology, degree of nerve degeneration, and duration of paralysis. Approaches can be broadly classified into three categories.

- Non-Operative: Eye Protection, Physiotherapy, Monitoring

- Static Procedures: Eyelids, Forehead, Neck

- Dynamic Procedures: Nerve and Muscle Procedures

Decision-Making Process

Facial nerve injury management depends on nerve function, muscle viability, and proximal stump presence — early injuries with a stump allow for direct repair or grafting, while those without (and late injuries) require cross-face nerve grafts, cranial nerve transfers, or free muscle transfers. The streamlined approach involves,

Assess Nerve Function

- Adequate Function: Improve symmetry by weakening the unaffected side.

- Inadequate Function: Augment the affected side using a cross-face nerve graft or cranial nerve transfer.

For Early Injuries (Viable Facial Muscle)

- Proximal Nerve Stump Present: Proceed with direct repair or ipsilateral nerve grafting.

- No Proximal Nerve Stump: Opt for a cross-face nerve graft or cranial nerve transfer.

For Late Injuries (Nonviable Facial Muscle)

- Proximal Nerve Stump Present: Use free muscle transfer to the ipsilateral facial nerve (VII).

- No Proximal Nerve Stump: Combine free muscle transfer with a cross-face nerve graft or cranial nerve transfer.

This approach helps determine the optimal management strategy based on injury timing and anatomical viability.

Non-Operative Management

While Bell’s palsy is a common cause of facial nerve palsy, non-operative management applies to a range of etiologies — including traumatic, infectious, and neoplastic causes.

- Medical Management: For inflammatory or viral-related palsies (e.g., Ramsay Hunt syndrome), early intervention with high-dose corticosteroids (ideally within 72 hours) is beneficial, and adjunct antiviral therapy may be warranted (Gilden, 2011).

- Eye Protection: For patients with incomplete eyelid closure, aggressive ocular management is critical. This includes lubricating drops, moisture chambers, and, in severe cases, temporary tarsorrhaphy to prevent exposure keratitis (Baugh, 2013).

- Facial Physiotherapy: Neuromuscular retraining and biofeedback can enhance recovery by promoting synkinetic movement and facilitating re-education of facial muscles.

- Monitoring and Prognostication: Electrophysiological studies (ENoG and EMG) are essential for prognosis: ENoG measures axonal degeneration (over 75% suggests poor outcome), while EMG (14–21 days post-onset) detects denervation via fibrillation potentials.

Static Procedures for Treating Facial Nerve Palsy

Static procedures aim to re-establish resting facial symmetry and improve functional deficits — such as protecting the cornea, enhancing nasal airflow, and reducing drooling — but do not restore dynamic facial movement.

These interventions are particularly indicated in,

- Patient Cohort: Elderly patients, medically unfit to undergo long surgery.

- Timing: established paralysis with nonviable facial musculature, temporary solutions for large facial defects (eg. oncological resection) (Fagan, 2014).

Non-Operative Static Treatment

- Botulinum Toxin Injections: Help manage synkinesis and improve facial asymmetry.

- Facial Fillers: Provide temporary volume correction for asymmetry.

- Physical Therapy: Rehabilitative exercises and neuromuscular retraining can improve static symmetry (Garcia, 2015).

Eyelid Procedures

- Tarsorrhaphy: Temporary or permanent eyelid closure to protect the cornea.

- Upper Eyelid Weight Implantation: Gold or platinum weights assist with passive eyelid closure, reducing corneal risk (Chen et al., 2010).

- Palpebral Springs/Lid Magnets: Alternative methods to improve eyelid function.

Brow and Forehead Procedures

- Müllerectomy: Corrects ptosis.

- Brow Lift/Suspension: Elevates a drooping brow.

- Forehead Skin Excision: Enhances brow elevation and reshapes the forehead.

Facial and Neck Procedures

- Unilateral Facelift-Type Procedures: Improve lower face symmetry.

- Static Slings/Fascial Suspension: Reposition drooping soft tissues to restore static balance.

- Platysmectomy: Addresses cervical synkinesis.

Müller’s muscle, an involuntary, sympathetically innervated muscle located below the levator aponeurosis and attached to the cephalad tarsal border, contributes 2–3 mm of eyelid elevation (Fagan, 2014).

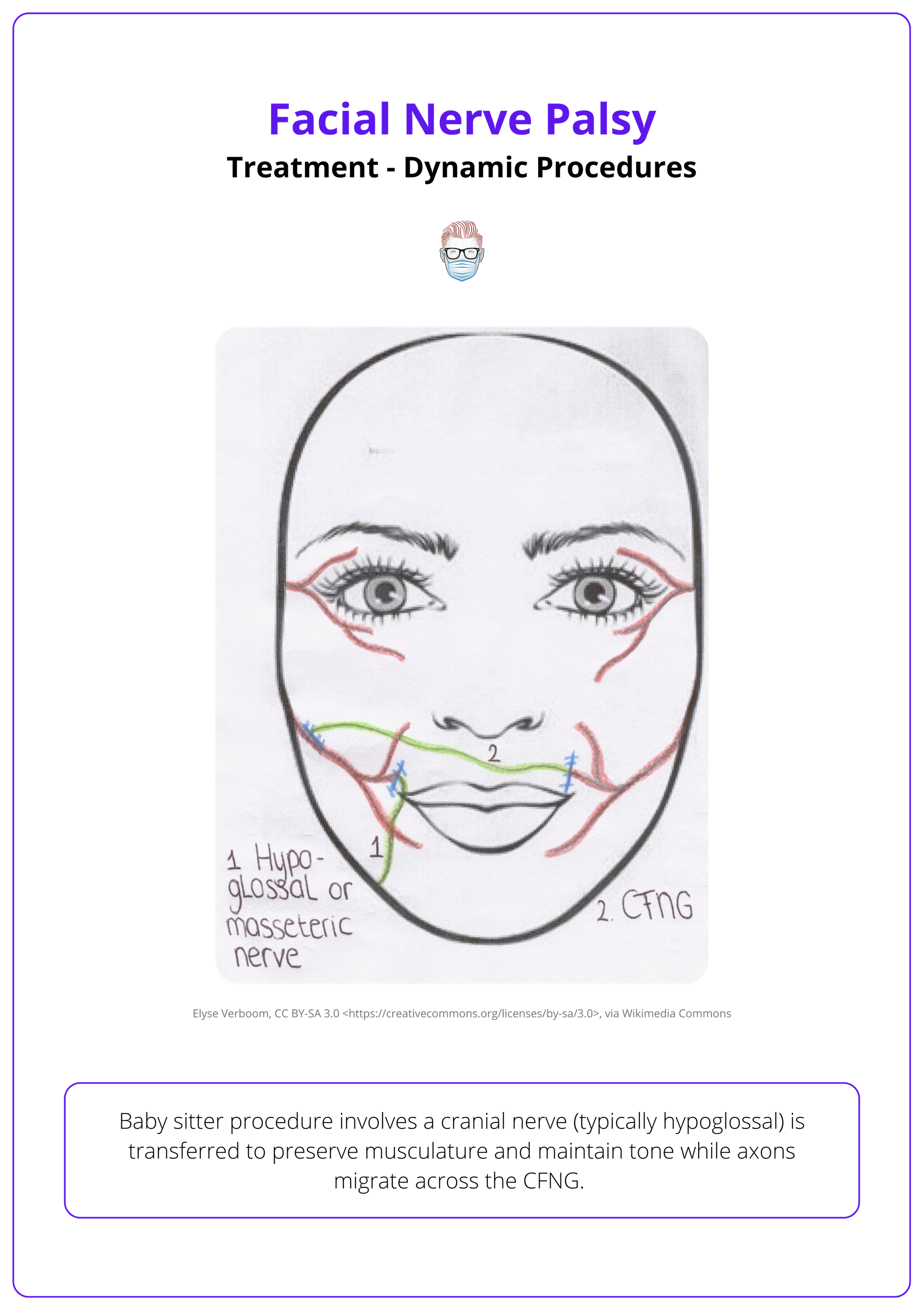

Dynamic Procedures for Treating Facial Nerve Palsy

Dynamic reanimation seeks to restore voluntary, spontaneous facial movement and improve overall function by addressing both nerve continuity and muscle function. The goal of these techniques is to,

- Re-establish a coordinated, symmetrical smile and improve facial tone for speech and eating (Coyle, 2013).

- Improve cheek tone, which enhances speech and the ability to eat.

Nerve-Related Procedures

- Primary Repair: Immediate direct repair in cases of acute transection or iatrogenic injury—ideally within 48–72 hours—to restore nerve continuity.

- Interposition Nerve Grafting: When direct repair is not possible, nerve grafts (e.g., sural nerve grafts) are used to bridge the gap, with early intervention optimizing outcomes

- CFNG: Cross facial nerve graft transfers motor axons from the unaffected side to reinnervate paralyzed muscles, serving as the first stage in two-stage reanimation.

- Nerve Transfers: Nerve transfers (e.g., masseter-to-facial) provide motor input when proximal regeneration is unlikely, while the babysitter procedure (using the hypoglossal nerve) maintains muscle tone during axonal migration (Fagan, 2014) in the CFNG.

The babysitter procedure for treating facial nerve palsy is illustrated below.

Nerve transfers options for facial reinnervation include the glossopharyngeal, spinal accessory, hypoglossal, and masseteric nerves.

Muscle Transfer

Longstanding facial nerve paralysis (>2 years) causing irreversible atrophy requires dynamic reanimation via regional or free muscle transfer.

- Free Muscle Transfer: In long-standing or complete paralysis, a free muscle transfer—commonly using the gracilis—reinnervated by a cross-facial nerve graft or nerve transfer restores dynamic movement, including smile and eye closure.

- Regional Muscle Transfer: For paralysis exceeding two years with irreversible muscle atrophy, regional muscle transfers or local flaps (e.g., masseter, temporalis) provide substitute musculature, sometimes combined with CFNG. Used when there is no functional mimetic muscle left for reinnervation.

Other muscles used for facial reanimation include the latissimus dorsi, rectus femoris, extensor digitorum brevis, serratus anterior, rectus abdominis, and platysma.

Complications of Facial Nerve Palsy

Facial nerve palsy can lead to a range of complications that impact vision, facial symmetry, and overall function. Prognosis varies based on factors such as the severity of the palsy, patient age, and treatment response.

Facial nerve palsy may result in a variety of complications that not only impair facial appearance but also compromise ocular health and overall facial function (Walker, 2023).

Important complications to be aware of include,

- Exposure Keratitis: Inadequate eyelid closure dries the cornea, increasing the risk of ulceration and infection.

- Hemifacial Spasm: Involuntary muscle contractions on one side of the face due to axonal degeneration.

- Synkinesis: involuntary facial movements during voluntary actions—for example, ocular-oral synkinesis (eye closure triggers mouth movement) and gustatory lacrimation ("Crocodile Tear Syndrome) (Ziahosseni, 2015).

Prognosis

Poor prognostic indicators include complete palsy, loss of the stapedial reflex, absence of recovery signs within three weeks, age over 50, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, and a poor response to electrophysiological testing (Walker, 2023).

Facial nerve function can continue improving for up to one year. Literature suggests the following timeline,

- Incomplete Bell’s Palsy: ~ 94% achieve full recovery (Finsterer, 2008).

- Complete Bell’s Palsy: ~20–30% may experience permanent disability without treatment.

When treated with corticosteroids — alone or combined with acyclovir — 94% of Bell’s palsy patients recover fully within 9 months (Finsterer, 2008).

Conclusion

1. Overview: Facial nerve palsy affects individuals aged 15-45, with Bell’s palsy being the most common cause. Other causes include trauma, infections, neoplasms, congenital conditions, and neurological disorders.

2. Clinical Assessment: Diagnosis involves history, examination of facial nerve function, and distinguishing neuron lesions. Investigations include blood tests, audiograms, EMG, and imaging. The House-Brackmann scale is used for grading.

3. Treatment Approaches: Static procedures improve symmetry at rest while dynamic procedures restore movement using nerve grafts, transfers, and free muscle flaps. Non-surgical options include physiotherapy, botulinum toxin, and corneal protection.

4. Complications & Prognosis: Risks include exposure keratitis, synkinesis, and facial asymmetry. Recovery depends on severity, age, and cause.

Further Reading

- Heckmann JG, Urban PP, Pitz S, Guntinas-Lichius O, Gágyor I. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Facial Paresis (Bell's Palsy). Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019 Oct 11;116(41):692-702. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0692. PMID: 31709978; PMCID: PMC6865187.

- Hohman MH, De Jesus O. Facial Nerve Repair. [Updated 2023 Aug 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Walker NR, Mistry RK, Mazzoni T. Facial Nerve Palsy. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Pinkiewicz M, Dorobisz K, Zatoński T. A Comprehensive Approach to Facial Reanimation: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2022 May 20;11(10):2890. doi: 10.3390/jcm11102890. PMID: 35629016; PMCID: PMC9143601

- Crawford KL, Stramiello JA, Orosco RK, Greene JJ. Advances in facial nerve management in the head and neck cancer patient. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Aug;28(4):235-240. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000641. PMID: 32628417.

- Rovak JM, Tung TH, Mackinnon SE. The surgical management of facial nerve injury. Semin Plast Surg. 2004 Feb;18(1):23-30. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823120. PMID: 20574467; PMCID: PMC2884690.

- Udagawa A, Arikawa K, Shimizu S, Suzuki H, Matsumoto H, Yoshimoto S, Ichinose M. A simple reconstruction for congenital unilateral lower lip palsy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Jul;120(1):238-244. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000264062.64251.10. PMID: 17572570.

- Garcia RM, Hadlock TA, Klebuc MJ, Simpson RL, Zenn MR, Marcus JR. Contemporary solutions for the treatment of facial nerve paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Jun;135(6):1025e-1046e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001273. PMID: 26017609.

- Fagan, J., Surgical Reanimation Techniques for Facial Palsy/ Paralysis Open access atlas of otolaryngology, head & neck operative surgery. page 1-13 2014.

- Ciorba A, Corazzi V, Conz V, Bianchini C, Aimoni C. Facial nerve paralysis in children. World J Clin Cases. 2015 Dec 16;3(12):973-9. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i12.973. PMID: 26677445; PMCID: PMC4677084.

- Walker NR, Mistry RK, Mazzoni T. Facial Nerve Palsy. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549815/

- Ziahosseini K, Nduka C, Malhotra R. Ophthalmic grading of facial paralysis: need for a closer look. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Sep;99(9):1171-5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305716. Epub 2015 Jan 6. PMID: 25563764.

- Finsterer J. Management of peripheral facial nerve palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Jul;265(7):743-52. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0646-4. Epub 2008 Mar 27. PMID: 18368417; PMCID: PMC2440925.

- Coyle M, Godden A, Brennan PA, Cascarini L, Coombes D, Kerawala C, McCaul J, Godden D. Dynamic reanimation for facial palsy: an overview. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013 Dec;51(8):679-83. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.12.007. Epub 2013 Feb 4. PMID: 23385066.