Summary Card

Overview

The DIEP flap (Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator) is an abdominally-based flap that spares rectus abdominis and rectus sheath. It is a gold standard for autologous breast reconstruction.

Vascular Anatomy

The DIEP flap blood supply originates from the external iliac artery, forming zones of abdominal wall perfusion.

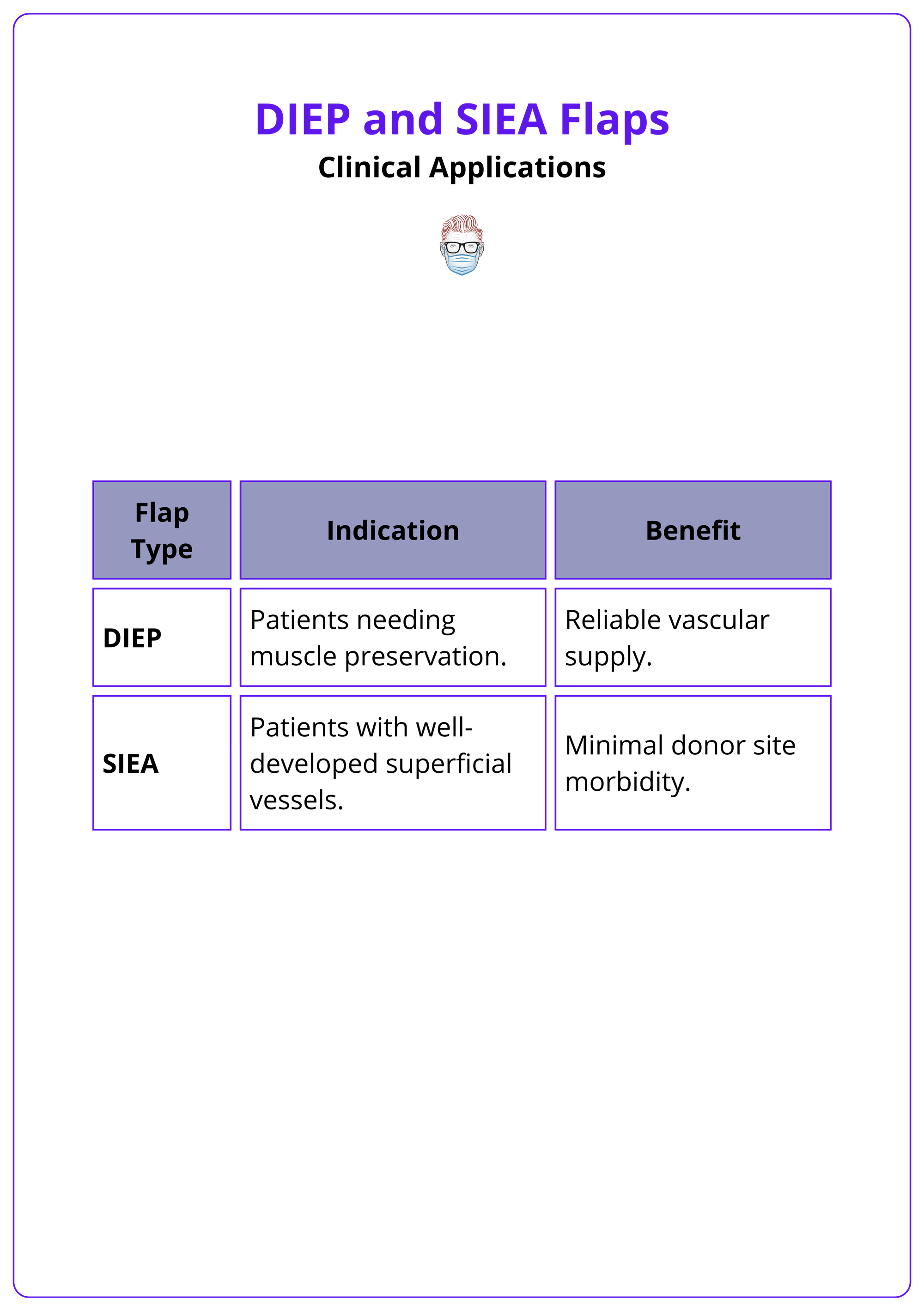

DIEP Flaps Compared to Other Techniques

The DIEP flap outperforms SIEA, TRAM, and expander-implant techniques in reliability, reduced donor-site morbidity, and long-term outcomes.

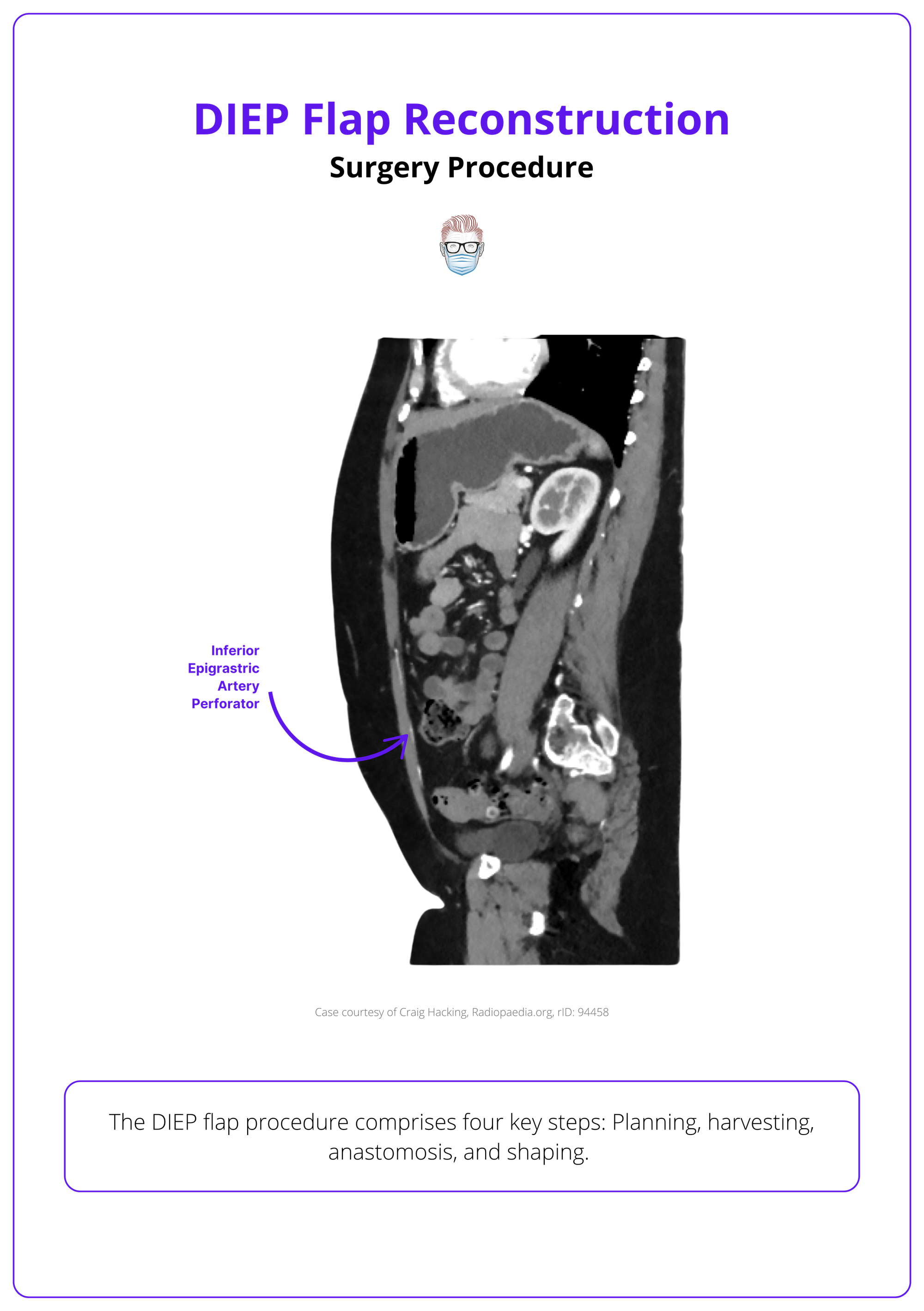

Surgery Procedure

The DIEP flap procedure comprises four key steps: Planning, harvesting, anastomosis, and shaping.

Complications

DIEP flap complications span intraoperative, perioperative, and long-term outcomes, affecting flap viability, donor site recovery, and overall surgical success.

Primary Contributor: Dr Hatan Mortada, Educational Fellow.

Overview of DIEP Flap

The DIEP flap is the gold standard for autologous breast reconstruction, utilizing abdominal skin and fat while preserving muscles and fascia.

The DIEP flap (Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator) is an abdominally-based flap that spares the rectus abdominis muscles and rectus sheath fascia. It offers significant advantages over other abdominal flaps.

- TRAM Flap: Incorporates muscle and fascia, increasing the risk of postoperative complications such as abdominal wall weakness and hernia.

- Muscle-Sparing TRAM (ms-TRAM): Reduces muscle removal but still involves variable fascia excision, with inconsistent techniques among surgeons.

- SIEA Flap: A viable alternative when superficial vessels are dominant, but it provides reduced tissue volume and has a higher risk of venous congestion compared to the DIEP flap.

A post-operative DIEP flap reconstruction is illustrated below.

Vascular Anatomy of DIEP Flap

The vascular anatomy of the DIEP flap primarily involves the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) which originates from the external iliac artery and supplies the flap through perforators in the abdominal wall.

The DIEP flap's blood supply originates from the external iliac artery, with perforators traversing the rectus abdominis to vascularize the flap. This creates a perfusion gradient in the abdominal wall, forming the basis for perfusion zones.

DIEP Flap Blood Supply

The Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery (DIEA) is the primary blood supply to the DIEP flap.

- Origin: external iliac artery, ~1 cm cranial to the inguinal ligament.

- Course: Traverses deep to the transversalis fascia and passes superficial to the arcuate line, supplying perforators to the anterior rectus sheath.

- Branches: Typically bifurcates into medial and lateral branches, though in ~28% of patients, it remains a single vessel.

- Measurements: 3–4 mm diameter, pedicle length: 14–18 cm, venous diameter: 3.5–4.5 mm.

Key Perforators

- Position: 2 cm above and 6 cm below the umbilicus, within 1–6 cm laterally (Ireton, 2014)

- Medial Perforators: Show greater branching and robust vascularity capable of crossing the midline (Wong, 2010)

- Lateral Perforators: Provide reliable vascularity only on the ipsilateral side, with limited midline perfusion.

The anatomical structure is illustrated below.

The Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery (SIEA) is a secondary blood supply to the DIEP flap. It can be chosen when the superficial vessels are well-developed.

- Origin: Common femoral artery, ~2–3 cm below the inguinal ligament (17% of cases), often sharing origin with the superficial circumflex artery (48%) but absent in ~35%.

- Measurements: arterial diameter 0.75–3.5 mm, pedicle length 4–7 cm, venous diameter 3–5 mm.

- Limitations: Inconsistent vessel presence (~35% absence rate), reduced tissue volume compared to the DIEP flap, and higher risk of venous congestion if venous dominance shifts to superficial systems.

These vessels are illustrated below.

Abdominal Zones of Perfusion

Hartrampf's Zones of Perfusion classify the lower abdominal flap into four zones. It strongest at the central axis and decreasing toward the periphery across the adipocutaneous tissue.

- Zone I always correlates to the zone of the selected perforator. This is most perfused and is the most reliable for flap reconstruction.

- Zone II is adjacent to zone I on the contralateral hemi-abdomen.

- Zone III is lateral to zone I

- Zone IV is lateral to zone II. This is a distant one, least perfused and unlikely to be viable.

In 2006, Holm et al. revised the Hartrampf zones, dividing the lower abdominal flap into an ipsilateral half with axial supply and a contralateral half with random supply, recommending the reversal of zones II and III.

The image below illustrates these four vascular zones described by Hartrampf.

Zone IV is typically avoided in flap design due to insufficient perfusion, but it may occasionally be included with careful vascular evaluation.

DIEP Flaps Compared to Other Techniques

The DIEP flap outperforms SIEA, TRAM, and expander-implant techniques in reliability, reduced donor-site morbidity, and long-term outcomes, making it the preferred choice for autologous breast reconstruction.

The DIEP flap stands out as the preferred choice for many surgeons due to its balance of reliable vascularity, reduced donor-site morbidity, and superior long-term outcomes compared to SIEA, TRAM, and expander-implant techniques.

SIEA Flaps

- Arterial Complications: Higher rates of arterial compromise and anastomotic revisions compared to DIEP flaps, reducing reliability (Selber, 2008).

- Tissue Volume: Provides less tissue volume than DIEP flaps, limiting its applicability in larger reconstructions.

- Indications: Suitable when superficial vessels are dominant, but overall less favored due to higher complication rates.

TRAM Flaps

- Pedicled TRAM Flaps: Involves muscle and fascia removal, leading to higher rates of donor-site complications such as hernia and abdominal wall weakness (Jeong, 2018).

- Muscle-Sparing TRAM (ms-TRAM): Reduces muscle removal but still involves fascia excision, with variable techniques across surgeons, resulting in inconsistent outcomes.

- DIEP Advantage: By preserving muscle and fascia, DIEP flaps have significantly lower rates of donor-site morbidity while maintaining similar flap viability.

Expander-Implant Reconstruction

- Initial Complications: Lower immediate complication rates compared to DIEP flaps.

- Long-Term Outcomes: Higher reconstructive failure and infection rates make expander-implant reconstruction less durable over time (Bennett, 2018).

- Patient Satisfaction: DIEP flaps provide better satisfaction and quality of life, as reported in studies using BREAST-Q scores (Liu, 2014).

DIEP Flap Surgery Procedure

The DIEP flap procedure comprises four key steps: Planning, harvesting, anastomosis, and shaping.

The DIEP flap procedure can be broken down into four key components: Preoperative planning, flap harvesting, microsurgical anastomosis, and flap shaping and inset, each critical for achieving optimal reconstructive outcomes.

Preoperative Preparation

- Imaging: Preoperative CT or MR angiography identifies dominant perforators.

- Marking: Surface markings design an elliptical flap (~13 cm high, 35–40 cm wide) tapering laterally for closure, with the lower incision placed near the pubic tubercle for optimal vessel visualization.

- Anaesthetic Setup: Includes venous access, Doppler monitoring, and patient positioning with calf pumps and drapes.

The marking and imaging are as illustrated below.

Cesarean scars can be incorporated into the design to prevent multiple transverse scars and minimize vascular compromise.

Flap Elevation

- Incisions and Dissection: Perform precise dermal and subcutaneous dissection to Scarpa’s fascia. Use beveling incisions cranially to recruit additional volume.

- Perforator Identification: Match perforators to imaging for optimal vascular supply. Isolate the perforator, ensuring arterial pulsatility and adequate venous caliber.

- Pedicle Exposure: A myotomy is performed to dissect deep inferior epigastric artery perforators through the rectus abdominis muscle, preserving muscle integrity, continuity, and innervation.

- Pedicle Dissection: Trace the pedicle intramuscularly, preserving intercostal motor nerves, and gaining adequate length for vascular integrity.

Some Surgeons often assess the presence and adequacy of SIEA vessels, opting for an SIEA flap if the vessels are well-developed.

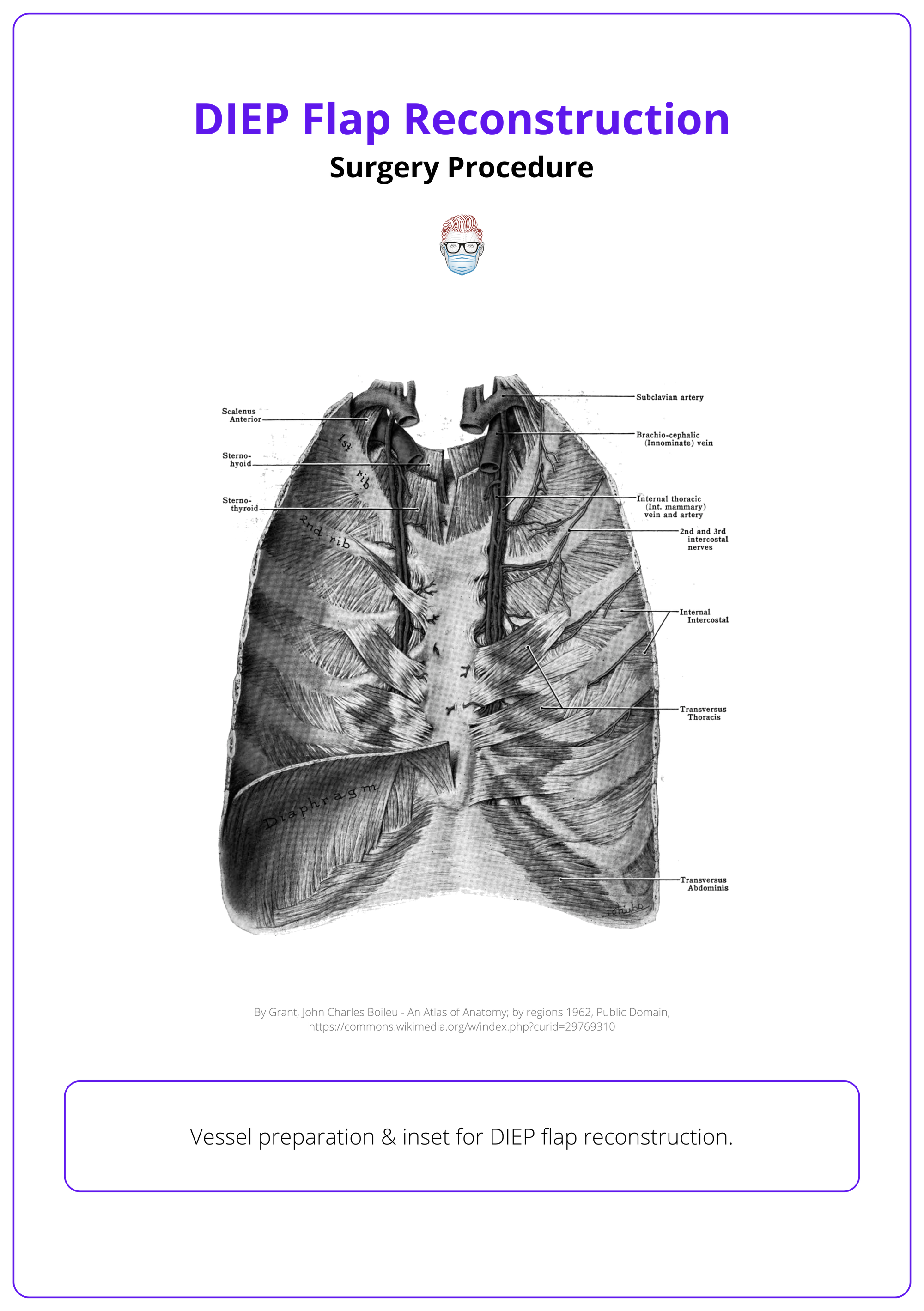

Vessel Preparation & Inset

- Chest Preparation: Rib-sparing techniques reduce morbidity without increasing flap complications.

- Recipient Vessel Dissection: Expose internal mammary or thoracodorsal vessels, with internal mammary vessels now preferred for better flap positioning, enhanced medial and superior pole fullness, and preservation of the latissimus dorsi flap for future use.

- Microsurgical Anastomosis: Complete arterial and venous connections, ensuring flow with Acland’s test.

- Flap Inset: Rotate the flap 180° and inset into the breast pocket. Ensure tension-free placement with the pedicle free from kinking or compression.

The related anatomy is illustrated below.

If the internal mammary vein is unavailable, the cephalic vein can be used as the primary recipient vein or as secondary outflow to enhance venous drainage in superficial-dominant flaps.

Abdominal Closure

- Layered Closure: Muscle and fascia are reapproximated in their original orientation to preserve abdominal wall strength. Barbed sutures and mesh may be used for reinforcement, especially in cases of umbilical hernia repair or increased risk of abdominal bulge.

- Umbilical Reconstruction: The neo-umbilicus is reconstructed or preserved, depending on hernia presence and vascular integrity.

Flap Monitoring

Effective flap monitoring combines clinical assessment and technology, with most flap compromises occurring within the first 24 hours postoperatively.

Clinical assessment of flap viability includes,

- Capillary Refill: Ensures adequate perfusion.

- Doppler Signals: Monitors arterial and venous flow.

- Flap Warmth and Color: Indicators of proper circulation.

Postoperative monitoring employs a range of techniques, including,

- Clinical Examination: Reliable and cost-effective, with comparable flap salvage rates to advanced technologies.

- Handheld Doppler: A widely used and effective tool for assessing flow.

- Implantable Doppler: Offers continuous monitoring but may result in false positives (~1.0%) and unnecessary reoperations (Carruthers, 2019).

- Near-Infrared Tissue Oximetry: Advanced imaging with high false-positive rates, requiring careful interpretation.

Postoperative Care

Key steps for postoperative care include,

- Drain Management: Secure drains to maintain fluid balance.

- Patient Positioning: Optimize positioning to reduce strain on the flap.

- Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols.

In SIEA flap planning, the design is limited to Zones I and II, as the vascular supply does not reliably extend beyond these areas.

Complications of DIEP Flaps

DIEP flap complications span intraoperative, perioperative, and long-term outcomes, affecting flap viability, donor site recovery, and overall surgical success.

The DIEP Flap comes with potential complications that can affect the flap, donor site, and overall surgical outcome. Key complications to be aware of include:

Flap-Related Complications

- Total Flap Loss: Rates are low, ranging from 0.9% to 2.0% (Heidekrueger, 2021).

- Partial Flap Necrosis: Varies between 0.1% and over 10%, depending on definition (Lie, 2013).

- Fat Necrosis: Comparable to pedicled TRAM flaps but influenced by flap thickness and vascular supply (Jeong, 2018).

- Venous Congestion: The most common cause of flap failure, necessitating timely intervention (Lie, 2013).

Donor Site Complications

- Hernias and Bulging: Lower rates with DIEP flaps compared to TRAM flaps, reflecting reduced muscle and fascia removal (Jeong, 2018).

- Wound Healing Issues: Can arise from suboptimal donor site closure techniques

Long-Term Outcomes

- Satisfaction and Quality of Life: DIEP flaps outperform expander-implant reconstruction in patient-reported outcomes, including BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction and quality of life (Liu, 2014).

- Additional Procedures: Secondary surgeries such as nipple reconstruction, contour refinement, and scar revisions are often required to enhance aesthetic outcomes (Hammond, 2021).

Due to vascular variability, the SIEA flap has higher rates of flap loss and related complications compared to the DIEP flap (Coroneos, 2015)

Conclusion

1. Classification and Overview: DIEP flaps are classified based on vascular anatomy and are a key technique in autologous breast reconstruction, prioritizing muscle preservation and reliable vascularity.

2. Vascular Anatomy: The DIEP flap's vascular supply mainly comes from the DIEA, originating from the external iliac artery. An alternative, the SIEA, is used less frequently due to its inconsistent presence.

3. Procedure Steps: DIEP flap surgery involves precise preoperative planning, perforator dissection, microsurgical anastomosis, and flap shaping to achieve optimal outcomes.

4. Advantages and Comparisons: DIEP flaps surpass TRAM and SIEA flaps by minimizing donor-site morbidity, enhancing long-term satisfaction, and maintaining robust vascular supply.

5. Complications: Potential risks include flap loss, fat necrosis, and venous congestion, but DIEP flaps have lower donor-site complications compared to TRAM flaps.

Further Reading

- Kehr, Pierre, and Alain G. Graftiaux. "Kayvan Shokrollahi, Lain S. Whitaker, Foad Nahai: Flaps: Practical reconstructive surgery: Thieme Verlag New York, Stuttgart, Delhi, Rio de Janeiro, 2017, 711 pp.; num Ill. Hardcover, 253.37€, ISBN: 978-1-60406-715-6." (2018): 329-329.

- Mathes SJ, Nahai F. Reconstructive Surgery: Principles, Anatomy, and Technique. 1997.

- Neligan, Peter, and James C. Grotting. Plastic Surgery: Breast. Vol. 5. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012.

- Hamdi M, Ghanem AM. "Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flaps and Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery Flaps for Breast Reconstruction." Plastic Surgery Textbook.

- Cormack GC, Lamberty BG. "The Arterial Anatomy of Skin Flaps." Springer-Verlag.