Summary Card

Definition of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome arises from ulnar nerve compression within the cubital tunnel, leading to motor and sensory deficits.

Anatomy of the Cubital Tunnel

The ulnar nerve originates from C8-T1. The tunnel is formed by FCU fascia, Osborne’s ligament, medial epicondyle and olecranon.

Diagnosis of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Little & ulnar-sided ring finger paresthesia, reduced grip strength, clawing & Fromen sign. Tinel’s and elbow flexion tests positive.

Investigations of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Diagnosis is clinical, supported by nerve conduction studies. In specific cases, ultrasound, MRI, or X-rays might be needed.

Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Involves therapy, analgesics, and surgical options: simple decompression, anterior transposition, and medial epicondylectomy. Non-surgical approaches are effective in mild cases.

Contributors: Bryce Stash, MD, Monika Martinek, MS3, Natalie Gaio, MD

Definition of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

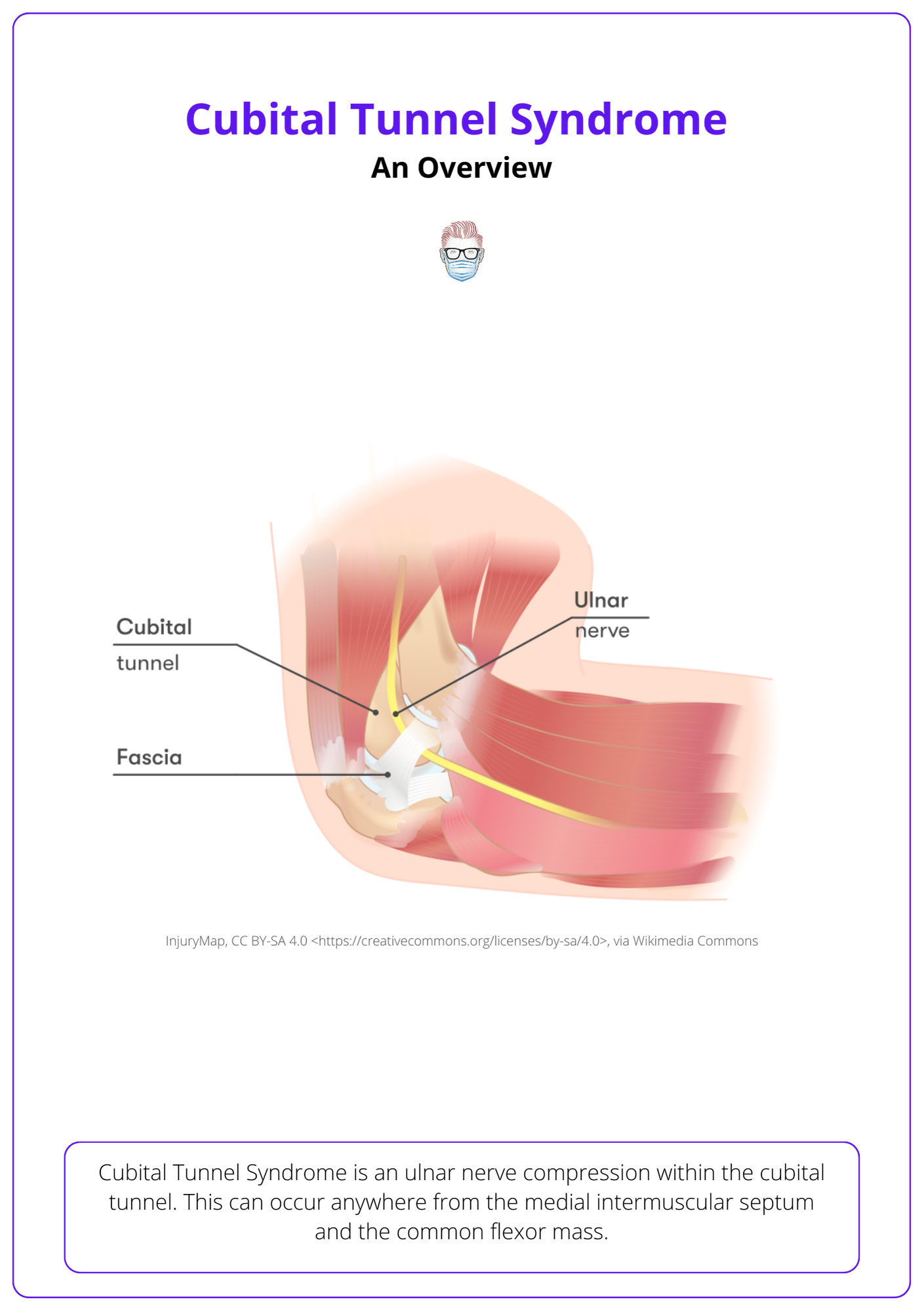

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome is an ulnar nerve compression within the cubital tunnel. This can occur anywhere from the medial intermuscular septum and the common flexor mass.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome arises from the compression of the ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel, manifesting as motor and sensory deficits. It ranks as the second most common compressive neuropathy (Andrews, 2018). The below image gives an overview of the Cubital Tunnel Syndrome.

Common sites of compression are:

- FCU Fascia: forms the arcuate ligament with Osborne Ligament.

- Ligament of Osborne: roof of the cubital tunnel.

- Arcade of Struthers: band from intermuscular septum to medial triceps.

- Medial Intermuscle Septum

- Epicondyle

Anatomy of the Cubital Tunnel

The ulnar nerve, originating from C8-T1, navigates the cubital tunnel with boundaries defined by FCU fascia, Osborne’s ligament, medial epicondyle, olecranon, and surrounding ligaments.

The ulnar nerve, originating from C8-T1, is a branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus.

Before the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve's course transitions from the anterior compartment (posteromedially to the brachial artery) to the posterior compartment (adjacent to the medial head of the triceps).

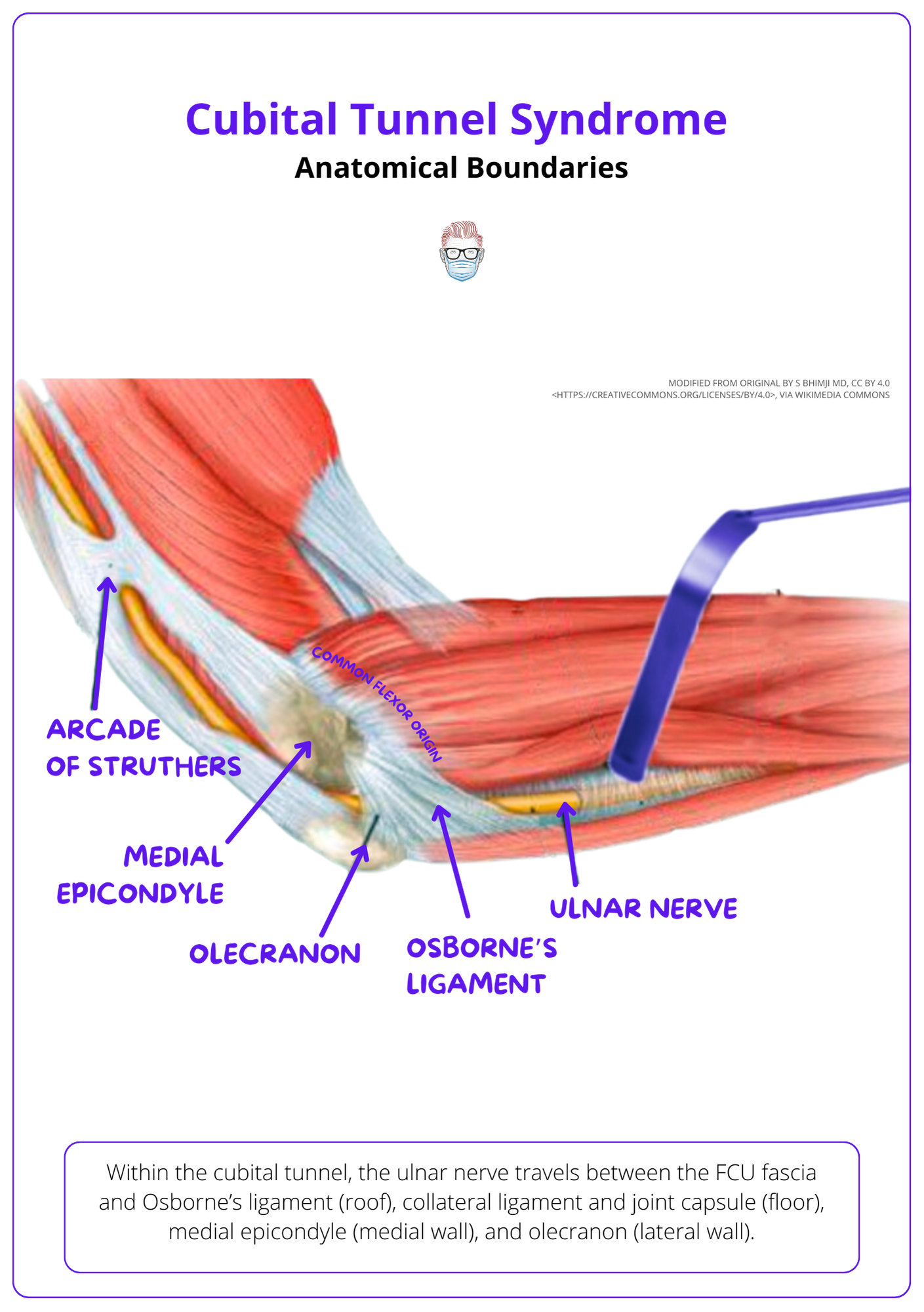

In the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve travels within well-defined anatomical boundaries. This is visualised in the image below.

- Roof: FCU fascia and Osborne’s ligament

- Floor: collateral ligament, joint capsule

- Medial Wall: Medial epicondyle

- Lateral Wall: Olecranon

Below image visualizes the anatomical boundaries of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome.

Other important landmarks include:

- Arcade of Struthers: tendinous band between intermuscular septum and triceps. It arises ~8cm proximal to the medial humeral condyle.

- Intermuscular Septum: continuous from the humeral medial epicondyle to the coracobrachialis muscle.

- FCU muscle: the nerve exits the cubital tunnel under Osborne's ligament and enters the forearm through the two heads of the FCU muscle.

Diagnosis of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

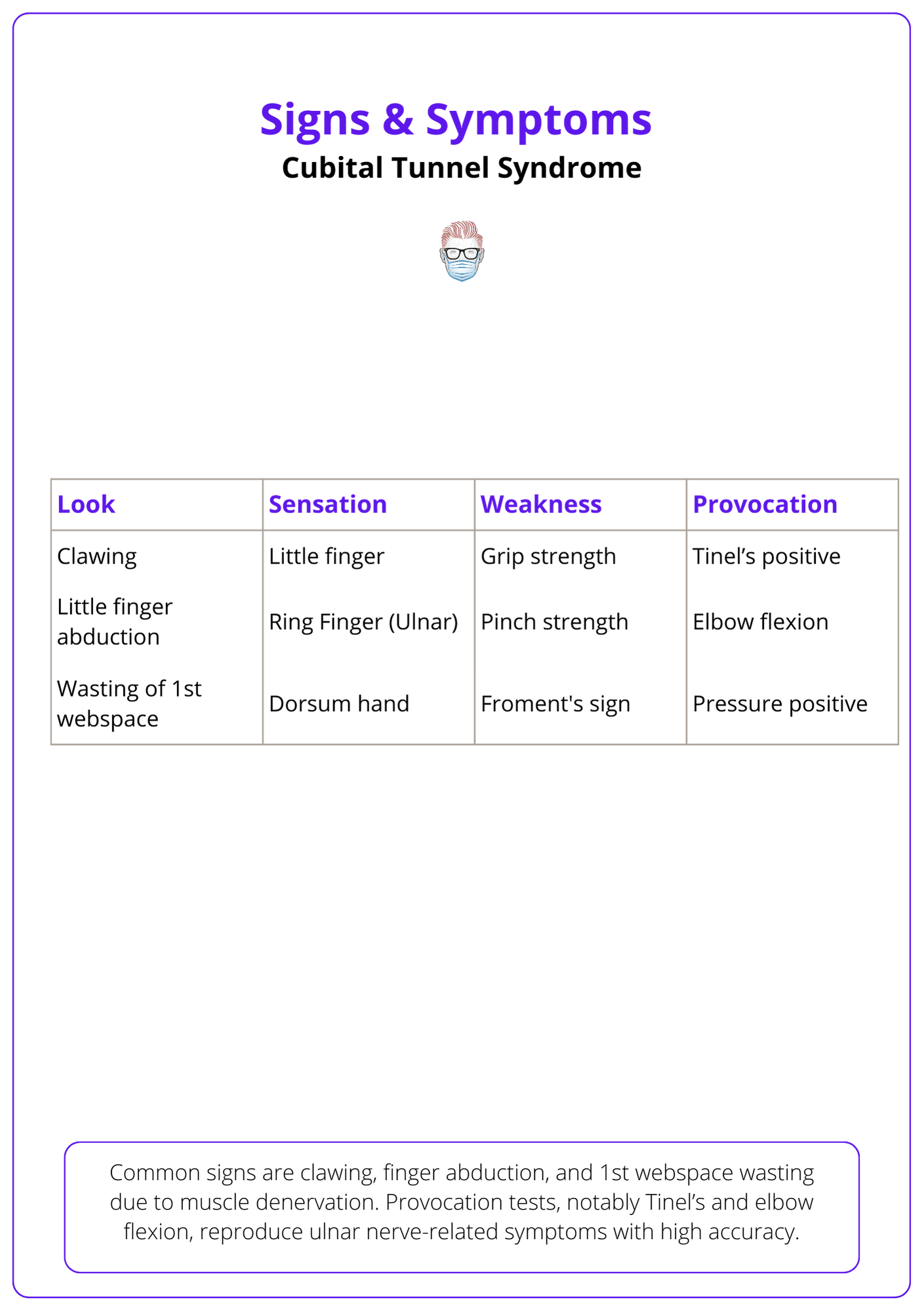

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome manifests with finger paresthesia and decreased grip strength. Physical exams reveal clawing and finger abduction, with Tinel’s and elbow flexion tests assisting the diagnosis.

History

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome is a progressively worsening condition marked by both motor and sensory deficiencies.

It is characterized by:

- Sensory: paresthesia of little and ulnar side of ring finger, worse at night.

- Motor: reduced grip strength.

A summary of the clinical features is visualised below.

Physical Exam

Inspection

On inspection, common observations are clawing, little finger abduction (Wartenberg Sign), and 1st webspace wasting

- Clawing is caused by intrinsic muscle denervation, leading to an unopposed pull by EDC and FDP tendons.

- Little finger abduction is due to weakened ulnar nerve-innervated 3rd palmar interosseous and small finger lumbrical.

- Wasting of 1st webspace is due to adductor pollicis atrophy.

This can be visualised in the images below.

Less frequently observed during examination are:

- Jeanne Sign: Thumb MCP hyperextension and adduction due to radial nerve-innervated EPL, countering the loss of IP extension and thumb adduction from the ulnar nerve-regulated adductor pollicis.

- Masse Sign: A flattened palmar arch and reduced ulnar hand elevation, attributed to weakened opponens digiti quinti and diminished small finger MCP flexion.

Feel

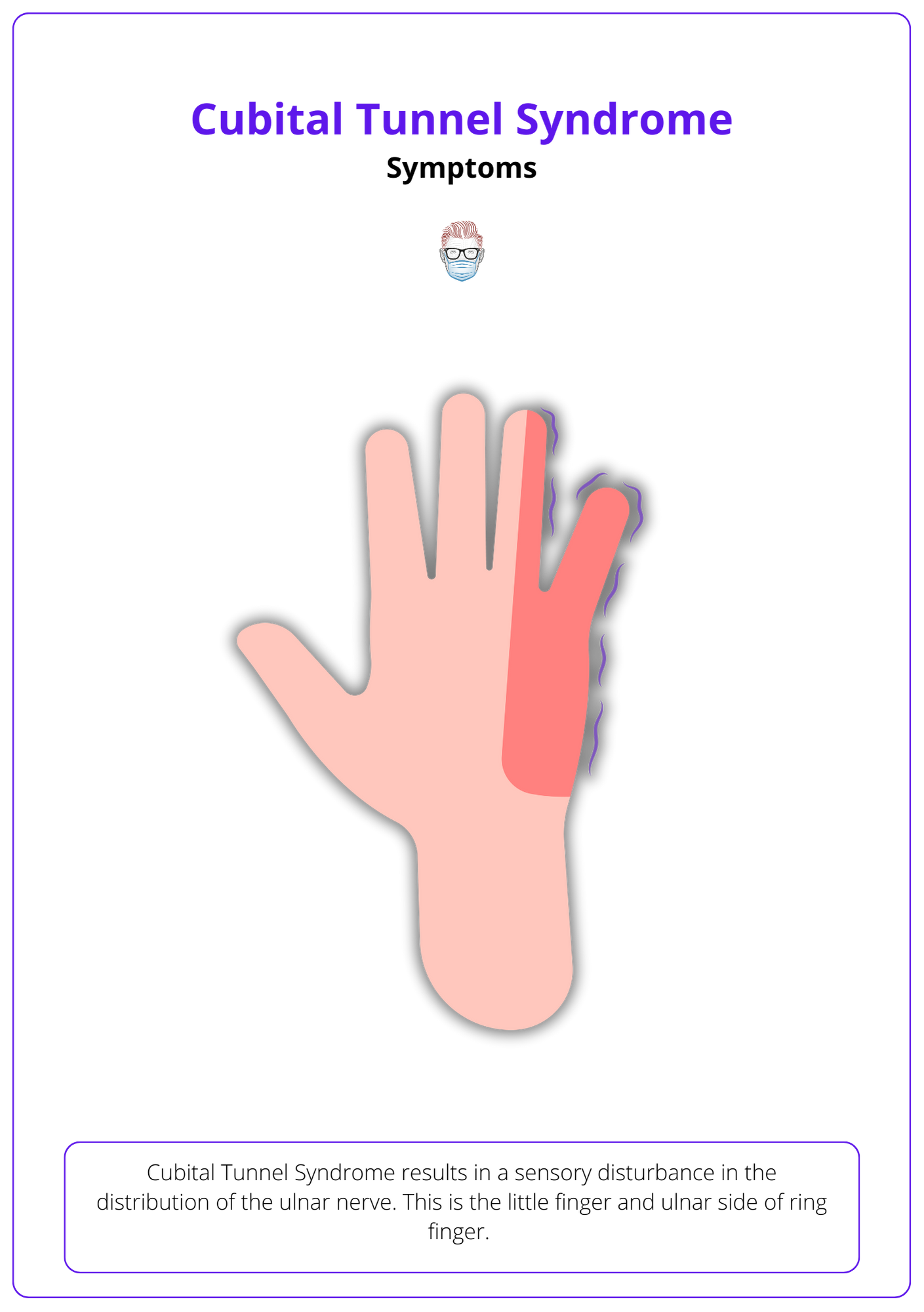

The sensory examination is typically straightforward, focusing on disturbances in the ulnar nerve distribution. Specifically:

- Diminished sensation in the little finger and the ulnar side of the ring finger.

- Decreased sensation on the dorsal aspect of the wrist, corresponding to the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve.

This sensory disturbance is visualized below.

Move

Cubital tunnel syndrome patients characteristically have reduced power in muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve. More specifically:

- Intrinsic muscle weakness reduces fine motor.

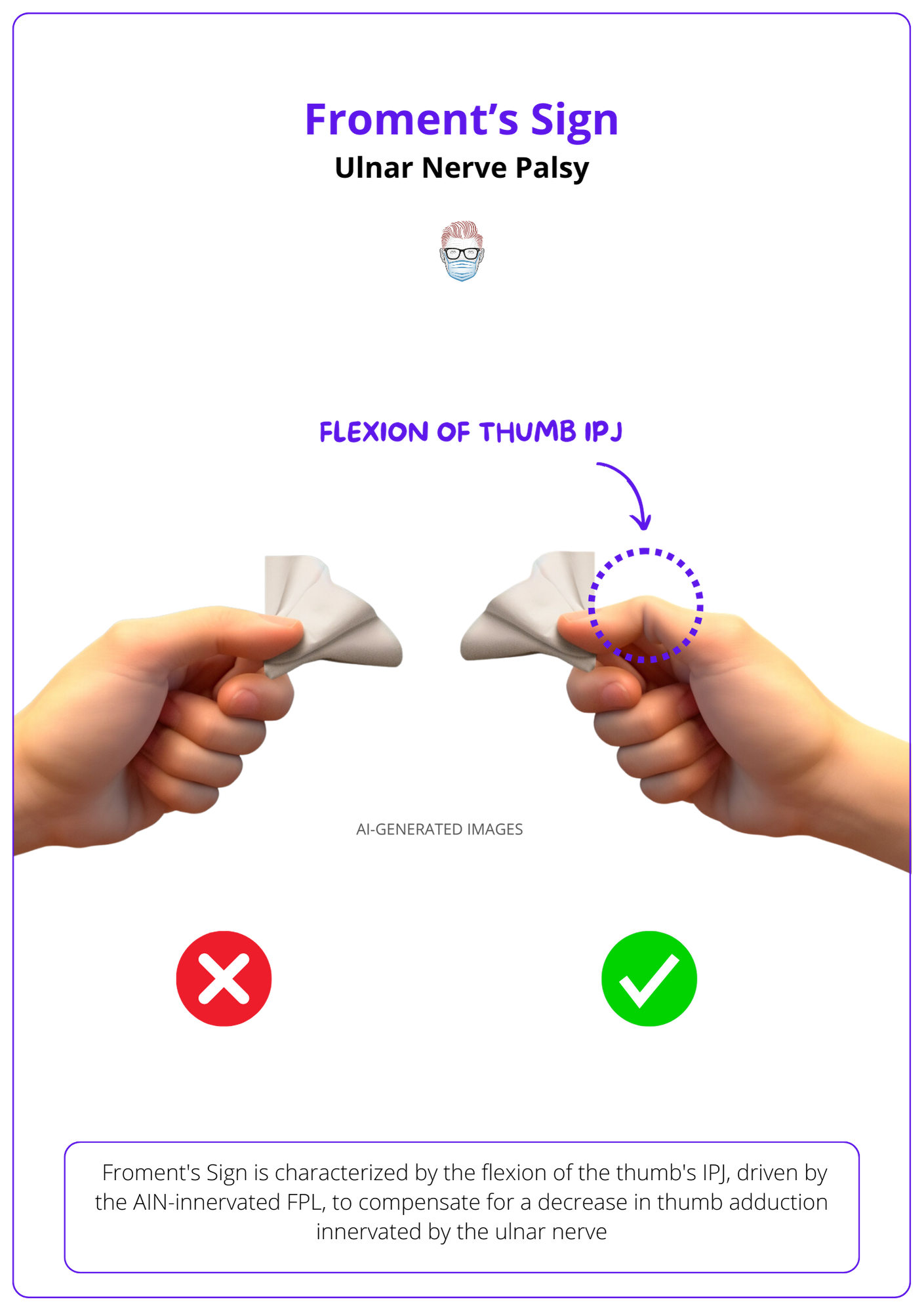

- Adductor Pollicis weakness reduces grip, pinch strength and enables Froment's sign.

- Subluxation of ulnar nerve over medial epicondyle with elbow flexion.

The Froment Sign is visualised below. Thumb's IPJ flexes (via AIN-innervated FPL) compensating for reduced thumb adduction (ulnar nerve-innervated).

Provocation Tests

Successful provocation tests will reproduce symptoms like paresthesias and/or numbness in the ring finger, little finger, or ulnar section of the dorsum hand.

- Tinel’s positive at cubital tunnel: 70% sensitive, 98% specific (Pandey, 2014).

- Elbow flexion for 60 seconds: 75% sensitive, 99% specific (Pandey, 2014).

- Pressure positive at cubital tunnel (Goldman et al, 2008).

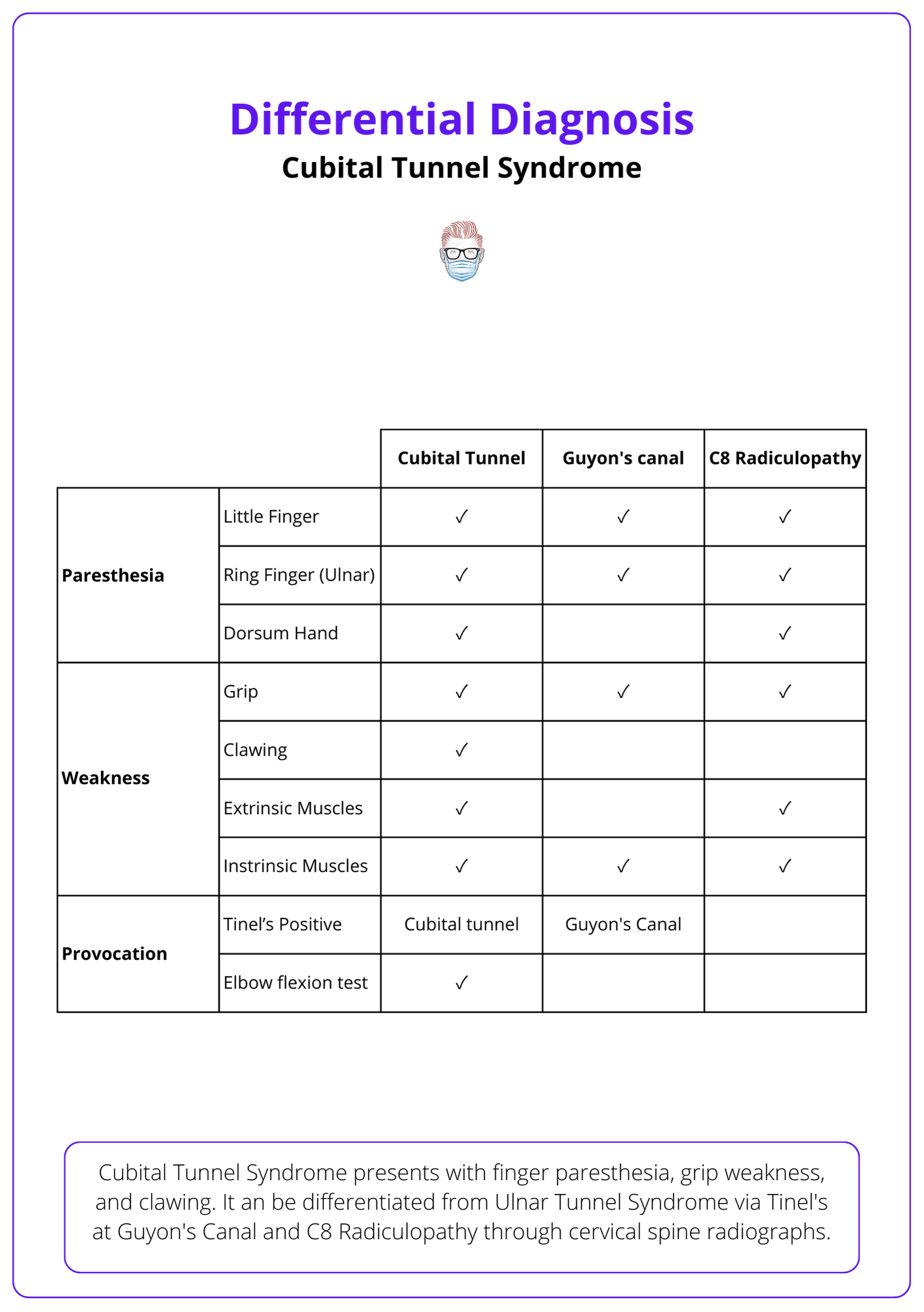

Differential Diagnosis

Cubital tunnel syndrome should be clinically differentiated from other ulnar nerve pathology. For example:

Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome is the compression of the nerve in Guyon's canal.

- Sensation: No dorsum hand sensory disturbance.

- Motor: No extrinsic muscle motor issues.

- Provocative: Positive Tinel's at Guyon's Canal.

C8 radiculopathy is compression at the spine.

- Sensation: Paresthesias in the small finger and ring finger.

- Motor: deficits in extrinsic and intrinsic motor movements.

- Differentiated by ordering cervical spine radiographs (Andrews et al, 2018).

The main differences between the common differentials are visualised below:

· Grade 1: Neuropathies with no weakness

· Grade 2: Neuropathies with muscle weakness

· Grade 3: Neuropathies with atrophy.

Investigations of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis which can be supported by nerve conduction studies. In select cases, imaging may be required.

Nerve Conduction Studies

Nerve conduction studies can be used for the diagnosis and prognosis of nerve compression (Tang, 2015).

Key points for interpretation are:

- Amplitude: CMAP (motor nerves) and SNAPS (sensory nerves) represent the number of functional axons. If reduced, velocity is less reliable.

- Conduction Velocity represents the degree of delamination and localises the site of compression (less accurate if CMAPS are reduced). This is considered significant if <50 m/s across the elbow (Landeau et al, 2013).

These create an injury pattern that can help predict postoperative outcomes.

- Demelyination has a favourable recovery: reduced velocity, normal CMAP.

- Axonal has an unfavourable recovery: reduced velocity, reduced CMAP

- Conduction block has favourable recovery: CMAP 50% at elbow compared to the wrist.

Imaging

- Ultrasound: high-frequency ultrasound of 14 Hz, ulnar nerve cross-sectional area of 0.065 squared cm (Landeau et al, 2013).

- MRI: aids in the visualization of the ulnar nerve (Landeau et al, 2013).

- X-ray: helps in the diagnosis of ulnar nerve compression caused by the presence of bone spurs, fractures, or arthritis (Landeau et al, 2013).

Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Treatment involves upper limb therapy, analgesics, and surgical methods like simple decompression, anterior transposition (with subcutaneous, intramuscular, and submuscular variations), and medial epicondylectomy.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome treatment integrates the expertise of upper limb therapists, analgesics, and surgical interventions. The three primary surgical techniques have been found to produce satisfactory outcomes (Boone, 2015).

- Simple decompression

- Anterior transposition: subcutaneous, intramuscular, submuscular

- Medial epicondylectomy

Simple Decompression

- Incision: 8-10 cm behind medial epicondyle in the ulnar groove.

- Dissection: Be cautious of the MABC located ~3 cm distal to the medial epicondyle in the subcutaneous plane.

- Release: Medial intramuscular septum, Arcade of Struthers, Osbourne’s ligament, Arcuate ligament, Deep flexor/pronator aponeurosis.

Anterior Transposition

This technique is combined with a simple decompression. It places the ulnar nerve anterior to the medial epicondyle, eliminating tension on the nerve with elbow flexion. Variations of this transposition include:

- Subcutaneous: transposition within subcutaneous tissue.

- Submuscular: transposition by detaching & reattaching flexor-pronator mass from the medial epicondyle.

- Intramuscular: transposition with a fascial sling.

This can be visualised in the video below by Dr Susan McKinnon.

Submuscular Ulnar Nerve Transposition - Standard (Feat. Dr. Mackinnon)

Medial Epicondylectomy

This is a less common performance variation. It involves an oblique osteotomy in a plane midway between the coronal and sagittal planes.18 It is important to preserve the insertion of the MCL and repair the periosteum.

- Benefits: limited nerve dissection is required

- Risks: destabilizing the elbow by damaging the MCL.

Conclusion

1. Overview of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome: Gained insight into Cubital Tunnel Syndrome as a condition arising from ulnar nerve compression within the cubital tunnel, leading to motor and sensory deficits.

2. Anatomy and Pathophysiology: Acquired knowledge on the anatomy of the cubital tunnel, including its formation by the FCU fascia, Osborne’s ligament, and the medial epicondyle and olecranon, and how these structures relate to ulnar nerve compression.

3. Diagnostic Techniques: Learned the clinical presentation and diagnostic techniques for Cubital Tunnel Syndrome, including the significance of little and ulnar-sided ring finger paresthesia, reduced grip strength, and the utility of Tinel’s and elbow flexion tests.

4. Investigative Approaches: Understood the role of nerve conduction studies in diagnosing Cubital Tunnel Syndrome and when additional imaging like ultrasound, MRI, or X-rays might be beneficial.

5. Treatment Modalities: Explored treatment options ranging from therapy and analgesics to surgical interventions such as simple decompression, anterior transposition, and medial epicondylectomy, and the considerations for choosing each based on the severity of the condition.

Further Reading

- Andrews K, Rowland A, Pranjal A, Ebraheim N. Cubital tunnel syndrome: Anatomy, clinical presentation, and management. J Orthop. 2018 Aug 16;15(3):832-836. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.010. Erratum in: J Orthop. 2020 Dec 14;23:275. PMID: 30140129; PMCID: PMC6104141.

- Apfelberg DB, Larson SJ. Dynamic anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973 Jan;51(1):76-81. PMID: 4347108.

- Boone S, Gelberman RH, Calfee RP. The Management of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2015 Sep;40(9):1897-904; quiz 1904. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.03.011. Epub 2015 Aug 1. PMID: 26243318.

- Caliandro P, La Torre G, Padua R, Giannini F, Padua L. Treatment for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Nov 15;11(11):CD006839. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006839.pub4. PMID: 27845501; PMCID: PMC6734129.

- Landau ME, Campbell WW. Clinical features and electrodiagnosis of ulnar neuropathies. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013 Feb;24(1):49-66. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2012.08.019. Epub 2012 Oct 25. PMID: 23177030.

- OSBORNE G. Compression Neuritis of the Ulnar Nerve at the Elbow. Hand. 1970;2(1):10-13. doi:10.1016/0072-968X(70)90027-6

- Pandey T, Slaughter AJ, Reynolds KA, et al. Clinical orthopedic examination findings in the upper extremity: correlation with imaging studies and diagnostic efficacy. Radiographics : a Review Publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2014 Mar-Apr;34(2):e24-40. DOI: 10.1148/rg.342125061. PMID: 24617698.

- Tang DT, Barbour JR, Davidge KM, Yee A, Mackinnon SE. Nerve entrapment: update. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Jan;135(1):199e-215e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000828. PMID: 25539328.