Summary Card

Aeitology

Congenital brachial plexus palsy is reduced movement in the upper limb, most often thought to be secondary to traction during the birthing process.

Anatomy

Arising from C5 - T1 of the spinal cord, the brachial plexus has 5 main terminal branches; musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, axillary, and radial.

Presentation

A flaccid upper limb at birth, with or without Horner’s syndrome. Joint creases are present.

Classification

Nerve injury severity is graded by the Seddon and Sunderland classification. The extent of obstetric brachial plexus palsy is classified by Narakas.

Scoring Systems

Outcome measures like the Brachial Plexus Outcome Measure, Mallet Score, and Toronto Test Score help evaluate and track progress over time.

Investigations

Non-invasive imaging and electrophysiology are useful adjuncts, but surgical exploration is currently the most specific investigation.

Multidisciplinary Management

Dedicated multidisciplinary management improves outcomes. Early surgical exploration is advised for complete injuries or if biceps function fails to return in 3 months.

Primary Contributor: Dr Suzanne Thomson, Educational Fellow.

Reviewer: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow.

Obstetric brachial plexus injury, used synonymously with congeital brachial plexus palsy, implies causation.

Aetiology of Congenital Brachial Plexus Palsy

Congenital brachial plexus palsy is reduced movement in the upper limb, most often thought to be secondary to traction during the birthing process.

Congenital brachial plexus palsy is a flaccid paralysis of the arm at birth, where the passive range of movement is greater than the active (Evans-Jones, 2003). It can arise after both vaginal and cesarean deliveries due to:

- Excessive head traction away from the shoulder during labor.

- Pubic traction or fetal malposition, even without dystocia (Doumouchtsis, 2009)

- Birth hypoxia, indicating a multifactorial etiology (DeFrancesco, 2019).

Risk factors for this condition can be maternal, fetal, or at delivery.

- Maternal: Diabetes, Primigravida (first-time mother), Black & Hispanic race

- Fetal: Macrosomia, Female sex (DeFrancesco, 2019)

- Delivery: Shoulder dystocia, Low Apgar scores, Birth hypoxia

The first description of obstetric brachial plexus palsy is attributed to William Smellie, of Lanark, Scotland in 1764 (Smellie, 1764).

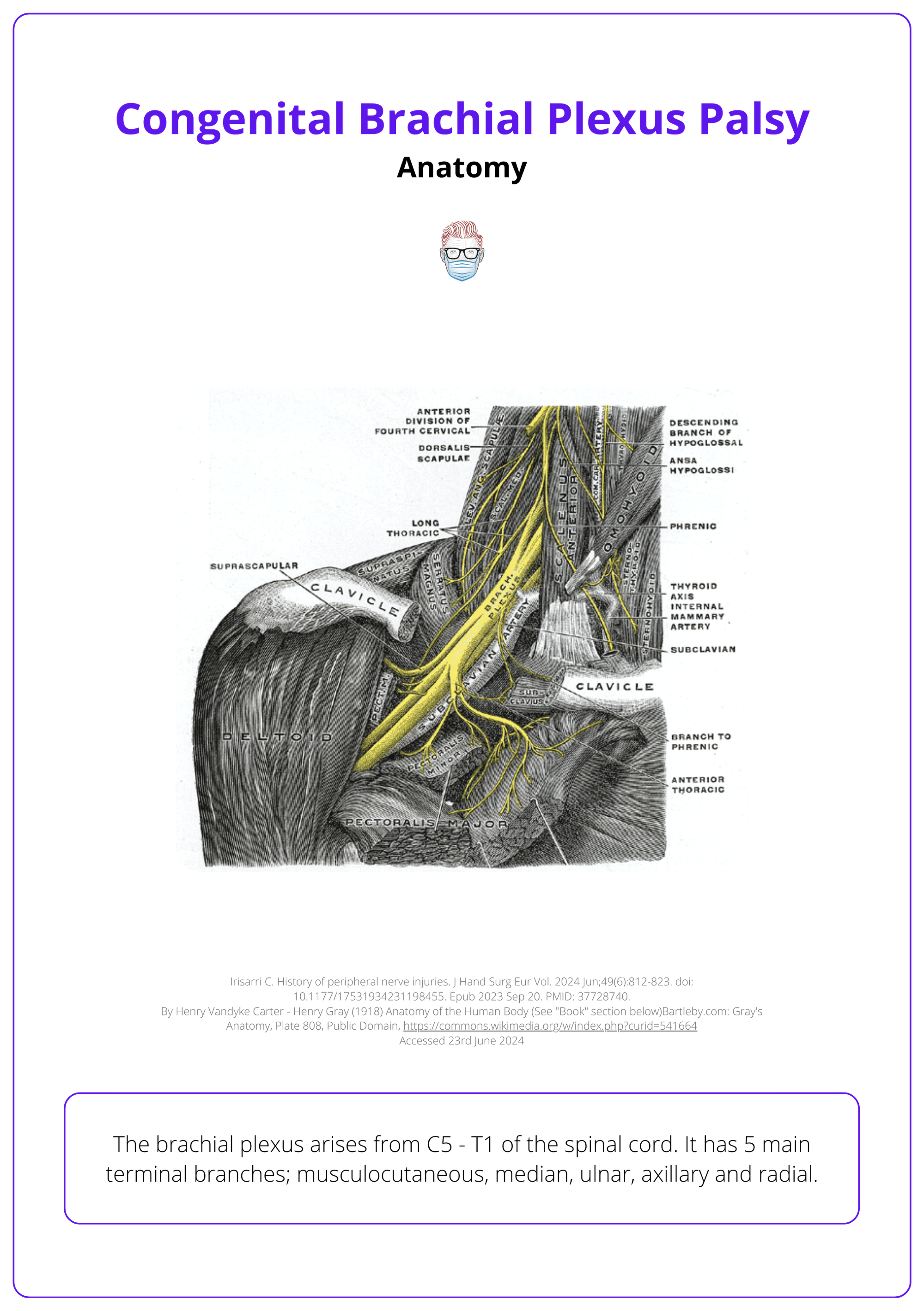

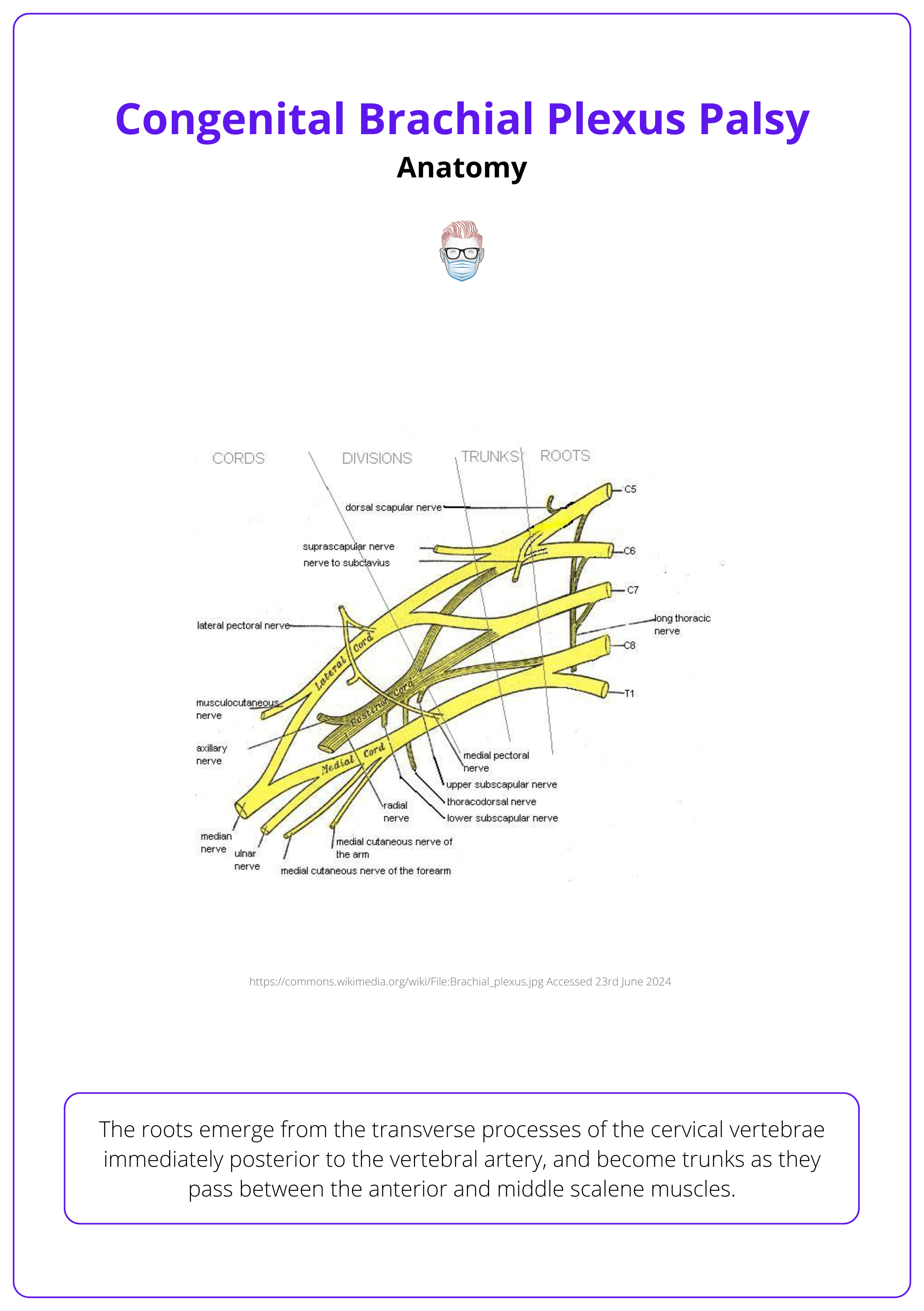

Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus arises from C5 - T1 of the spinal cord. It has 5 main terminal branches; musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, axillary, and radial.

The brachial plexus originates from roots C5 to T1, potentially extending from C4 to T2, and forms a key sensory and motor network connecting the upper limb to the central nervous system. It is organized into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches.

Roots

Located at the dorsal root ganglion for sensory neurons and anterior horn of the spinal cord for motor neurons; exit behind the vertebral artery.

Trunks & Divisions

Merge from roots passing between the anterior and middle scalene muscles—C5 and C6 (upper trunk), C7 (middle trunk), C8 and T1 (lower trunk).

Each trunk splits into anterior and posterior divisions.

Cords

Cords are named for their position relative to the axillary artery, extending from over the first rib under the clavicle:

- Lateral Cord: Originates from anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks, leading to the lateral pectoral nerve (C5-C7).

- Medial Cord: Emerges from the anterior division of the lower trunk, connecting to the medial pectoral, medial brachial cutaneous, and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves (C8, T1).

- Posterior Cord: Formed by the posterior divisions of all trunks, it gives rise to subscapular and thoracodorsal nerves (C5-C8).

Terminal Branches

Each cord supplies nerves to specific regions of the upper limb.

- Lateral Cord: Musculocutaneous nerve.

- Medial Cord: Ulnar nerve.

- Posterior Cord: Radial and axillary nerves.

- Combined Contribution: Median nerve from both lateral and medial cords.

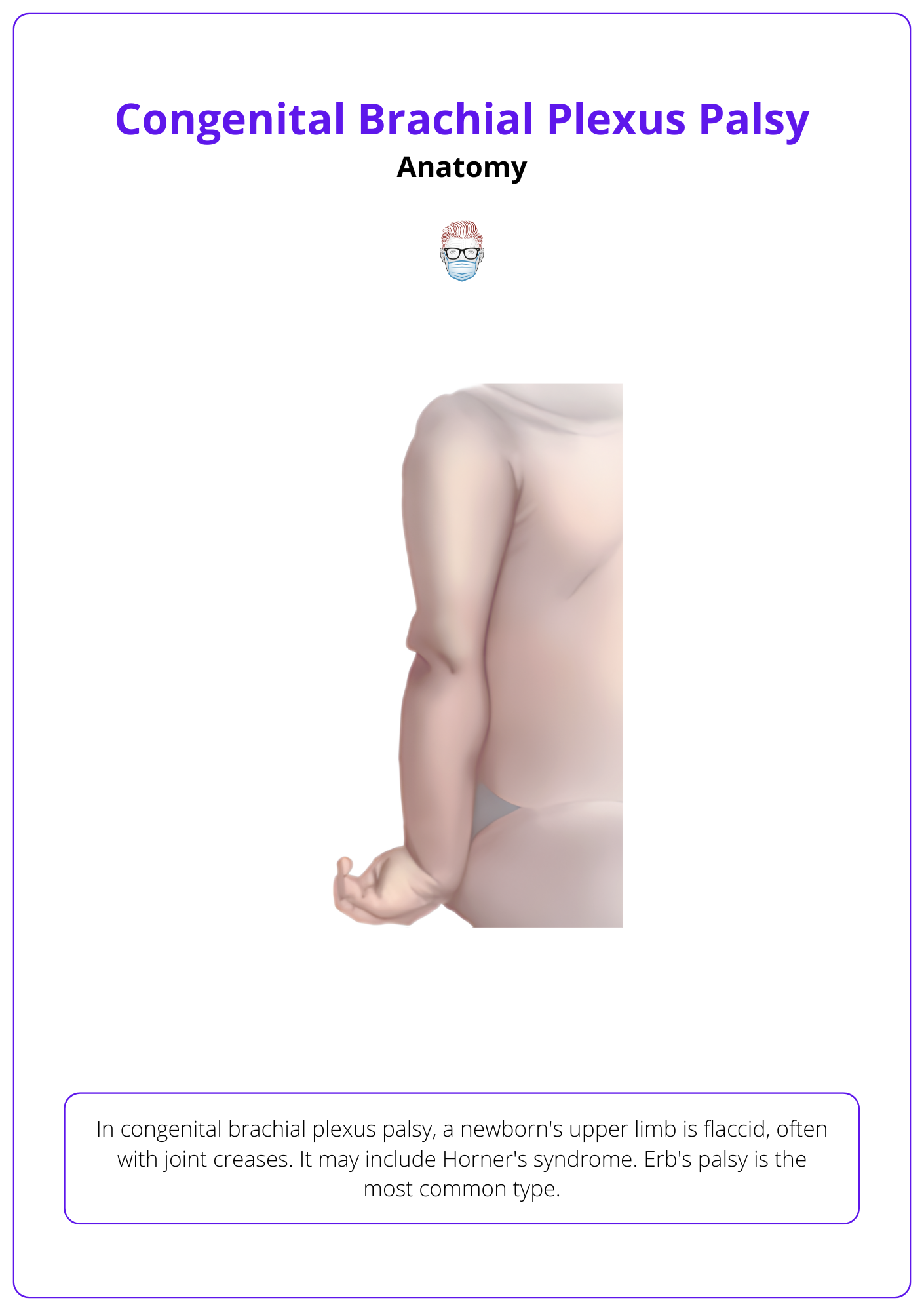

Presentation of Congenital Brachial Plexus Palsy

A flaccid upper limb at birth, with or without Horner’s syndrome. Joint creases are present. Erb's palsy is the most common.

The presentation of congenital brachial plexus palsy at birth may include a flaccid upper limb, with or without Horner’s syndrome. A temporal examination is important to determine the severity and the resolution.

Most cases are noticed immediately following delivery and may be transient or permanent depending on the severity of injury.

Horner’s syndrome is ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis due to damage of the sympathetic stellate ganglion.

Erb's Palsy

Erb’s Palsy, named after the German neurologist who first described it in 1874, primarily affects the upper plexus (C5, C6) and results in a “waiter's tip” posture.

- Shoulder: Abducted and internally rotated, affected by weakened abductors, latissimus dorsi, and pectoralis muscles.

- Elbow: Extended from biceps weakness with unopposed triceps action.

- Forearm: Pronated due to weakness in supination.

- Wrist: Flexed because of extensor weakness.

Importantly, normal creases are present, indicating movement occurred in utero. This is illustrated in the image below.

Erb’s palsy is often used as a term to describe all congenital brachial plexus palsies but in fact, describes the most common clinical presentation of C5 and C6 nerve root injury.

Other Manifestations

- Phrenic Nerve Involvement (C3, C4, C5): Can lead to respiratory symptoms or might only be detected via chest X-ray.

- Pan-Plexus Injury: Affects the entire plexus, resulting in a limp arm and possibly Horner’s syndrome if the stellate ganglion (near T1) is impacted.

- Klumpke’s Paralysis (C7, C8, T1): Noted for adequate shoulder control but limited wrist movement and diminished fine motor skills in the hand, making it the rarest type in birth-related injuries.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common differential diagnoses for pseudoparalysis are secondary to fractures (humerus or clavicle) and arthrogryposis (characterized by the absence of skin creases). Other potential differentials include:

- Spinal cord lesion

- Cerebral palsy

- Glenohumeral joint sepsis

- Infective plexopathy

- Radial nerve injury (usually self-limiting)

- Biceps trauma (very rare)

Spontaneous recovery may occur but is usually incomplete, especially in children where the lower roots are involved.

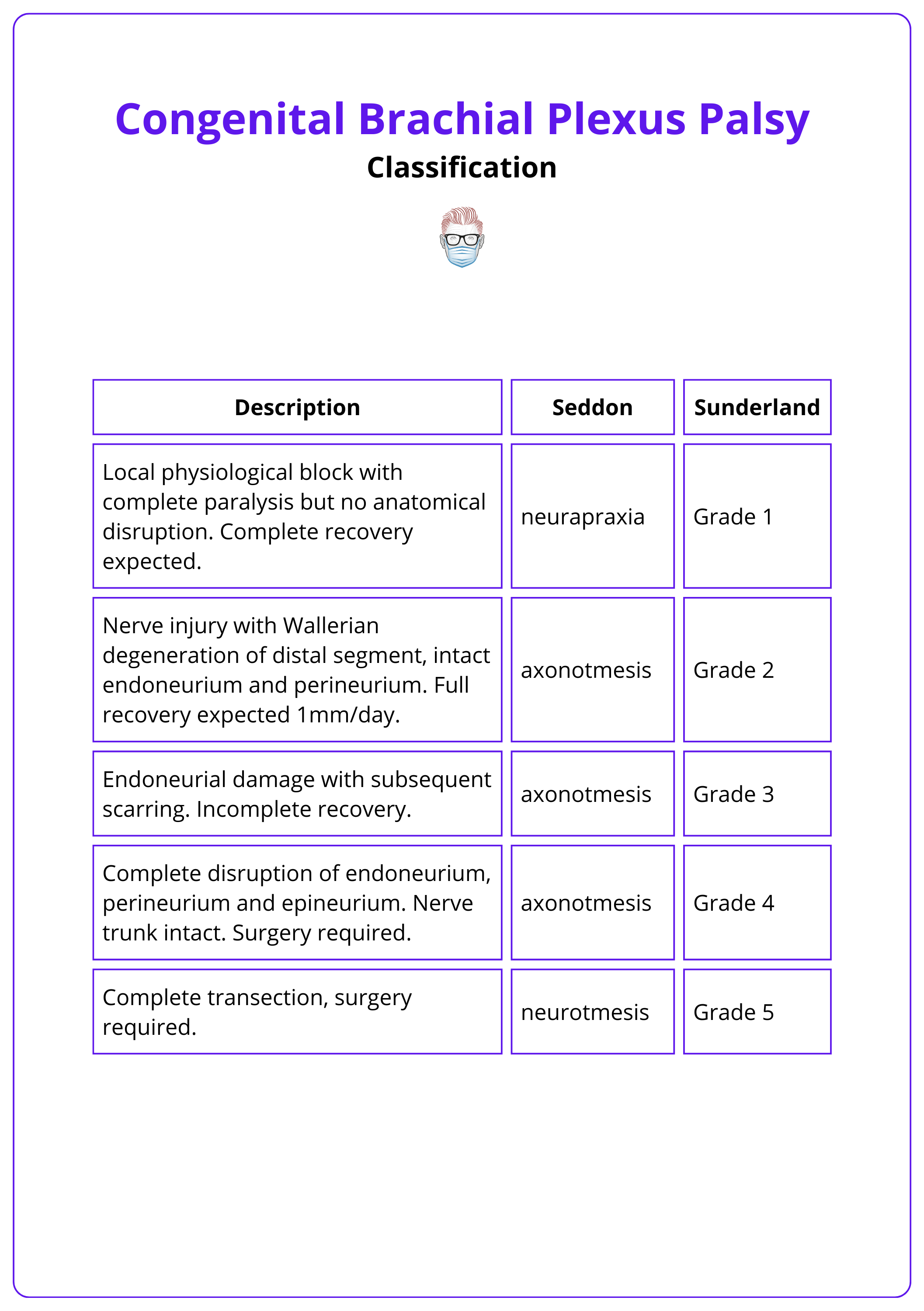

Classification of Congenital Brachial Plexus Palsy

Nerve injury severity is graded by the Seddon and Sunderland classification. The extent of obstetric brachial plexus palsy is classified by Narakas.

Classic Classifications

Seddon and Sunderland classified nerve injury according to the degree of structural damage. Grade 3-5 injuries (axonotmesis and neurotmesis) will not recover fully and operative intervention is indicated. MacKinnon added a sixth grade, to include the coexistence of mixed grades of injury within a scarred nerve.

This is detailed in the image below.

Narakas classification

This classification is widely used to describe the extent of congenital brachial plexus injury.

- Grade 1 (C5, C6): Lack of shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, forearm supination. (80% spontaneous recovery)

- Grade 2 (C5, C6, C7): Also includes lack of wrist extension. (60% spontaneous recovery)

- Grade 3: Pan-plexus with complete flaccid paralysis. (< 50% spontaneous recovery)

- Grade 4: Pan-plexus with complete flaccid paralysis and Horner’s syndrome. (< 50% spontaneous recovery)

In Narakas 2 palsy, the most common birth palsy, patients have a "good hand" whose usefulness is limited by lack of shoulder motion.

Scoring Systems

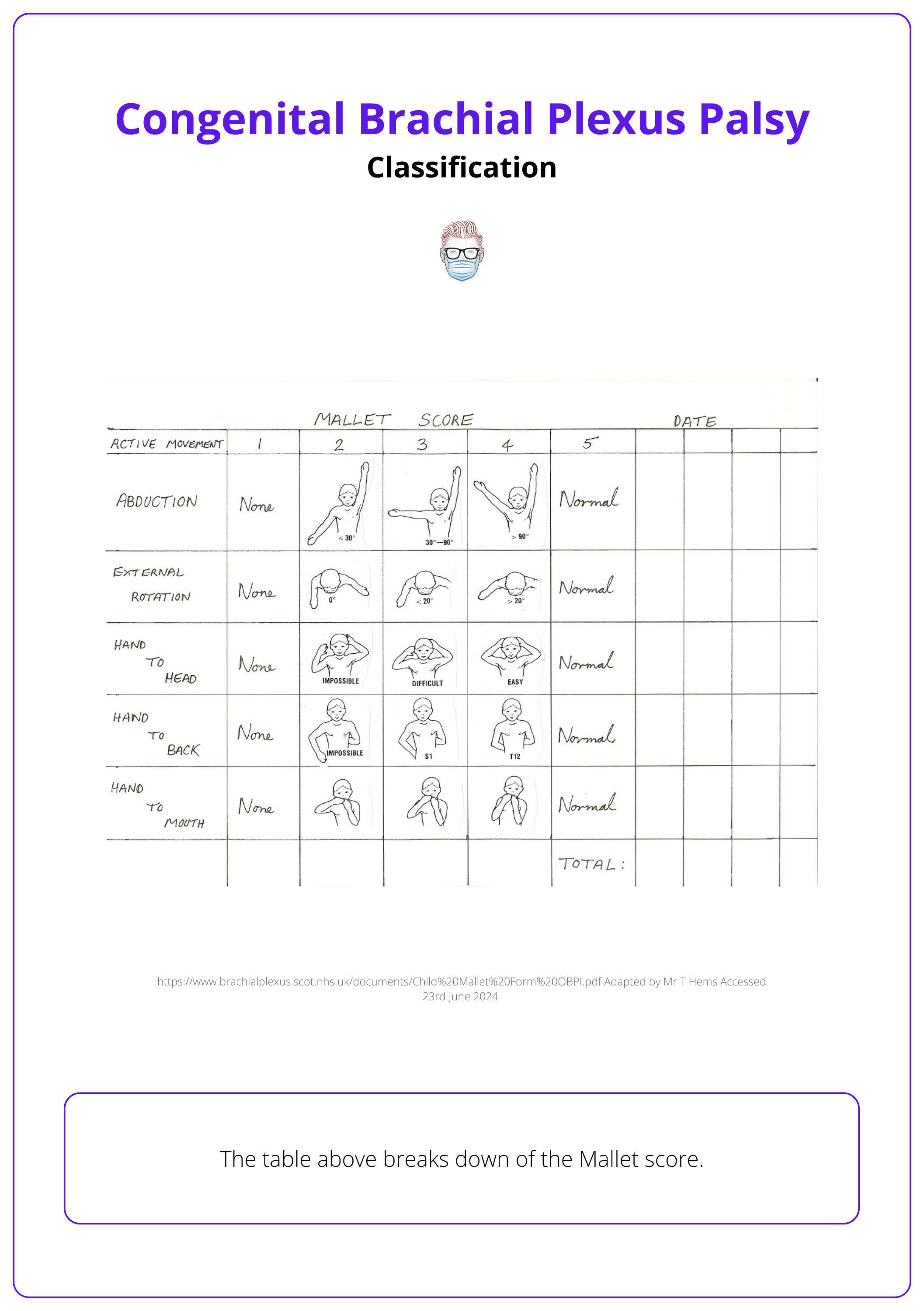

Outcome measures like the Brachial Plexus Outcome Measure, Mallet Score, and Toronto Test Score help evaluate and track progress over time.

Outcome measures help evaluate and track progress over time. Key systems include Brachial Plexus Outcome Measure, Mallet Score (Al Quattan, 2024) and Toronto Test Score (Michelow, 1994)

The Mallet Score is visualised below.

Toronto Score

This evaluates active joint movements against gravity to determine the need for surgery:

- Measurements: Elbow flexion/extension, wrist/finger/thumb extension.

- Scoring: 0 (no motion) to 2 (full motion), max score 10.

- Indicator: <3.5 at 3 months post-injury suggests surgical exploration.

Investigations for Congenital Brachial Plexus Palsy

Surgical exploration is the most definitive method for investigation, although non-invasive imaging and electrophysiology can also provide valuable insights.

Primarily diagnosed clinically, with prognosis and surgical decisions supported by investigations. Surgical exploration is the most thorough assessment method.

Diagnostic Imaging

- X-ray: Detects fractures or a raised hemidiaphragm.

- Ultrasound: Assesses shoulder joint alignment.

- MRI:

- T2-Weighted: Identifies nerve avulsions.

- Diffusion Tract Imaging (dTI): Analyzes nerve microstructure.

Intraoperative Electrophysiology

Stimulates muscles and detects sensory-evoked action potentials, enabling precise nerve function mapping during surgery.

Combining clinical evaluation of the phrenic nerve, nerve to serratus anterior, Tinel-Hoffman sign, Horner’s syndrome, and MRI increases diagnostic accuracy to 89%, compared to 80% with MRI alone for root avulsion. (Echalier, 2019).

Management of Congenital Brachial Plexus Palsy

Early surgical exploration is recommended for complete injuries or if biceps function does not return within 3 months, involving procedures like nerve reconstruction, neurolysis, grafting, transfers, osteotomies, and fusion.

Treatment for congenital brachial plexus palsy requires a multidisciplinary team including surgeons, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and orthotists. Surgery options include:

- Early Surgery: Directed at reconstructing the nerve injury.

- Late Surgery: Optimising function and correcting deformity.

Early Surgery

Early surgery focuses on nerve reconstruction. It is indicated in the following circumstances:

- Biceps function does not return by 3 months.

- Toronto test score below 3.5 at 3 months.

- Complete lesion (Narakas 4) with no recovery signs.

- Poor shoulder and forearm function at 9 months, despite some elbow function recovery (Argenta, 2016).

Nerve reconstruction is not recommended over 2 years post-injury due to muscle atrophy; muscle and tendon transfers are the preferred treatment.

The goal of early surgical exploration is to:

- Define the nerve injury

- Provide neurolysis

- Reconstruct nerve defect - sural nerve grafts or nerve transfers

- Optimise sensory return - important for central nervous system programming

Nerve Transfers

Nerve transfers are used primarily for root avulsions when nerve grafting isn't feasible. The most frequently employed early transfer is the spinal accessory to suprascapular nerve transfer for shoulder stabilisation. There are two main types:

Intra-Plexal Transfers:

- Nerve to flexor carpi ulnaris (from ulnar) and nerve to flexor carpi radialis (from the median) to biceps and brachialis branches of musculocutaneous (Oberlin/MacKinnon transfer).

- Medial pectoral to musculocutaneous (Brandt and MacKinnon).

- Triceps branch to axillary nerve (Leechongavong).

Extra-Plexal Transfers:

- Intercostal to musculocutaneous.

- Contralateral C7 transfer, often performed endoscopically.

- Supraclavicular C4 sensory nerves to C6, 7, and 8 stumps, if grafting is not possible - aims to restore C6 thumb and index finger sensation.

- Phrenic nerve transfer is less common due to its impact on respiratory function.

Nerve transfers can also be used to manage shoulder external rotation and elbow flexion deficiency at 12-18 months if there are sufficient donor nerves available to cover all targets (C5-C6 injuries) (Tse, 2015).

Increasingly, Botox is used early to target internal muscle rotators and reduce the risk of glenohumeral subluxation, complementing surgery, or serial casting (Grahn, 2023).

Muscle and Tendon Transfers

Muscle and tendon transfers correct deformities such as shoulder abduction, internal rotation, elbow flexion, forearm supination, wrist flexion, and ulnar deviation with specific corrective strategies.

- Shoulder: Subscapularis release, L’episcipo anterior release, teres major transposition, and rotator cuff/deltoid muscle transfers (Elhassan, 2010).

- Elbow: Elbow deformity correction involves anterior capsule release, biceps lengthening, Steindler flexorplasty, and muscle transfers including latissimus dorsi and pectoralis. For insufficient local muscle, gracilis transfer with intercostal nerves is used. (Kay, 2010).

- Forearm: Z-lengthening of the biceps for supination correction, FCU to brachioradialis transfer, and osteotomy for supination deformities (Hamdi, 2022)

- Wrist: FCU or FCR to ECRB, PQ to ECRB, and ECU to ECRB.

- MCPJ and IPJ Extensions: FCR and ECRL to EDC, distal EDC advancement, and lumbrical replacement by FDS.

- Thumb: EIP to APB, FDS to EPL transfers

Conclusion

1. Congenital Brachial Plexus Palsy: Gained knowledge about the condition, including its definition, causes, and anatomical aspects.

2. Clinical Presentation: Learned how the condition manifests at birth and the common forms it may take, such as Erb's palsy.

3. Diagnostic Approaches: Understood the key diagnostic tools and techniques used to evaluate brachial plexus palsy.

4. Treatment Strategies: Grasped the surgical and non-surgical management options available for treating the condition.

Further Reading

- Smellie W. Vol. 3. London: Wilson and Durham; 1764. Collection of Preternatural Cases and Observations in Midwifery.

- Evans-Jones G, Kay SP, Weindling AM, Cranny G, Ward A, Bradshaw A, Hernon C. Congenital brachial palsy: incidence, causes, and outcome in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003 May;88(3):F185-9. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.3.f185. PMID: 12719390; PMCID: PMC1721533.

- Hardie CM, Bourke G, Salt E, Fort-Schaale A, Clark S, Wiberg M, Bains R. Demographics and deprivation in obstetric brachial plexus palsy: a retrospective cohort study. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2024 May;49(5):570-575. doi: 10.1177/17531934231196421. Epub 2023 Sep 11. PMID: 37694876.

- Thomson SE, Ng NY, Riehle MO, Kingham PJ, Dahlin LB, Wiberg M, Hart AM. Bioengineered nerve conduits and wraps for peripheral nerve repair of the upper limb. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Dec 7;12(12):CD012574. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012574.pub2. PMID: 36477774; PMCID: PMC9728628.

- Kay S, Pinder R, Wiper J, Hart A, Jones F, Yates A. Microvascular free functioning gracilis transfer with nerve transfer to establish elbow flexion. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010 Jul;63(7):1142-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.05.021. Epub 2009 Jun 13. PMID: 19525160.

- Gilbert A. La réparation du plexus brachial dans les lésions obstétricales du nouveau-né [Repair of the brachial plexus in the obstetrical lesions of the newborn]. Arch Pediatr. 2008 Mar;15(3):330-3. French. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2007.12.008. Epub 2008 Mar 3. PMID: 18313907.

- Birch R. Timing of surgical reconstruction for closed traumatic injury to the supraclavicular brachial plexus. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015 Jul;40(6):562-7. doi: 10.1177/1753193414539865. Epub 2014 Jul 8. PMID: 25005560.

- Doumouchtsis SK, Arulkumaran S. Are all brachial plexus injuries caused by shoulder dystocia? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009 Sep;64(9):615-23. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181b27a3a. PMID: 19691859.

- Soucacos PN, Vekris MD, Zoubos AB, Johnson EO. Secondary reanimation procedures in late obstetrical brachial plexus palsy patients. Microsurgery. 2006;26(4):343-51. doi: 10.1002/micr.20249. PMID: 16628747.

- Al-Qattan MM. Tendon transfer to reconstruct wrist extension in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Br. 2003 Apr;28(2):153-7. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(02)00301-7. PMID: 12631488.

- Jaufuraully S, Lakshmi Narasimhan A, Stott D, Attilakos G, Siassakos D. A systematic review of brachial plexus injuries after caesarean birth: challenging delivery? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023 May 17;23(1):361. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05696-1. PMID: 37198580; PMCID: PMC10190031.

- DeFrancesco CJ, Shah DK, Rogers BH, Shah AS. The Epidemiology of Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy in the United States: Declining Incidence and Evolving Risk Factors. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019 Feb;39(2):e134-e140. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001089. PMID: 29016426.

- Lagerkvist AL, Johansson U, Johansson A, Bager B, Uvebrant P. Obstetric brachial plexus palsy: a prospective, population-based study of incidence, recovery, and residual impairment at 18 months of age. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010 Jun;52(6):529-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03479.x. Epub 2009 Dec 23. PMID: 20041937.

- Koshinski JL, Russo SA, Zlotolow DA. Brachial Plexus Birth Injury: A Review of Neurology Literature Assessing Variability and Current Recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2022 Nov;136:35-42. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2022.07.009. Epub 2022 Jul 20. PMID: 36084421.

- Hems T, Todd-Hems A. Obstetric brachial plexus injury in Scotland: incidence over 16 years. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2023 Jul;48(7):668-669. doi: 10.1177/17531934231166824. Epub 2023 Apr 18. PMID: 37070266.

- Steindler A. A Muscle Plasty for the Relief of Flail Elbow in Infantile Paralysis. Interstate Med J. 1918;2:235–241.

- Kossambe S, Kamath L, Diwakar KK. Descriptive Study of Obstetric Brachial Plexus Palsy (OBPP) at a Tertiary Care Hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2022 Dec;72(6):542-544. doi: 10.1007/s13224-021-01520-y. Epub 2021 Oct 6. PMID: 36506894; PMCID: PMC9732160.

- Hoeksma AF, ter Steeg AM, Nelissen RG, van Ouwerkerk WJ, Lankhorst GJ, de Jong BA. Neurological recovery in obstetric brachial plexus injuries: an historical cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004 Feb;46(2):76-83. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000179. PMID: 14974631.

- Dunkerton MC. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder associated with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989 Nov;71(5):764-6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B5.2684988. PMID: 2684988.

- MacNamara P, Yam A, Horwitz MD. Biceps muscle trauma at birth with pseudotumour formation: a cause of poor elbow flexion and supination in birth lesions of the brachial plexus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009 Aug;91(8):1086-9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.22125. PMID: 19651840.

- Echalier C, Teboul F, Dubois E, Chevrier B, Soumagne T, Goubier JN. The value of preoperative examination and MRI for the diagnosis of graftable roots in total brachial plexus palsy. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2019 Sep;38(4):246-250. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2019.06.001. Epub 2019 Jun 8. PMID: 31185314.

- Tassin, J. L. (1983). Paralysies obstétricales du plexus brachia, évolution spontanée, résultats des interventions réparatrices précoses (Doctoral dissertation, éditeur non identifié).

- Leblebicioğlu G, Pondaag W. Brachial plexus birth injury: advances and controversies. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2024 Jun;49(6):747-757. doi: 10.1177/17531934241231173. Epub 2024 Feb 16. PMID: 38366382.

- Al-Qattan MM, El-Sayed AA. Obstetric brachial plexus palsy: the mallet grading system for shoulder function--revisited. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:398121. doi: 10.1155/2014/398121. Epub 2014 Jan 5. PMID: 24527447; PMCID: PMC3909974.

- Kay S. Brachial palsies from obstetric procedures. Lancet. 1999 Aug 21;354(9179):614-5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00222-6. PMID: 10466658.

- Bourke G, Wade RG, van Alfen N. Updates in diagnostic tools for diagnosing nerve injury and compressions. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2024 Jun;49(6):668-680. doi: 10.1177/17531934241238736. Epub 2024 Mar 27. PMID: 38534079.

- Foad SL, Mehlman CT, Foad MB, Lippert WC. Prognosis following neonatal brachial plexus palsy: an evidence-based review. J Child Orthop. 2009 Dec;3(6):459-63. doi: 10.1007/s11832-009-0208-3. Epub 2009 Nov 3. PMID: 19885693; PMCID: PMC2782065.

- Grahn P, Pöyhiä T, Nietosvaara Y. Permanent Brachial Plexus Birth Injury: Helsinki Shoulder Protocol. Semin Plast Surg. 2023 Jul 14;37(2):108-116. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1768940. PMID: 37503533; PMCID: PMC10371410.

- Hussain S, Hussain A, Javed M, Cheema TA. Role of saha's procedure in change of movement at shoulder joint in traumatic brachial plexus injuries. JSZMC 2017;8(4):1277-80

- Hamdi NB, Doubi M, Abalkhail TB, Mortada H. Clinical and psychosocial outcomes following correction of supination deformity in obstetrical brachial plexus palsy patients: A retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022 Aug 24;23(1):808. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05765-0. PMID: 36002839; PMCID: PMC9400219.

- Michelow BJ, Clarke HM, Curtis CG, Zuker RM, Seifu Y, Andrews DF. The natural history of obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994 Apr;93(4):675-80; discussion 681. PMID: 8134425.

- Argenta AE, Brooker J, MacIssac Z, Natali M, Greene S, Stanger M, Grunwaldt L. Obstetrical brachial plexus palsy: Can excision of upper trunk neuroma and nerve grafting improve function in babies with adequate elbow flexion at nine months of age? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016 May;69(5):629-33. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2015.12.020. Epub 2016 Jan 7. PMID: 26806089.

- Leblebicioglu G, Ayhan C, Firat T, Uzumcugil A, Yorubulut M, Doral MN. Recovery of upper extremity function following endoscopically assisted contralateral C7 transfer for obstetrical brachial plexus injury. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016 Oct;41(8):863-74. doi: 10.1177/1753193416638999. Epub 2016 Mar 17. PMID: 26988920.

- Xu, W. D., & Gu, Y. D. (2016). Years for contralateral C7 transfer. Chin J Hand Surg, 32, 247-249.

- Bourke G, McGrath AM, Wiberg M, Novikov LN. Effects of early nerve repair on experimental brachial plexus injury in neonatal rats. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2018 Mar;43(3):275-281. doi: 10.1177/1753193417732696. Epub 2017 Sep 26. PMID: 28950736.

- West CA, Ljungberg C, Wiberg M, Hart A. Sensory neuron death after upper limb nerve injury and protective effect of repair: clinical evaluation using volumetric magnetic resonance imaging of dorsal root Ganglia. Neurosurgery. 2013 Oct;73(4):632-9; discussion 640. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000066. PMID: 23839516.

- Hart AM, Terenghi G, Wiberg M. Neuronal death after peripheral nerve injury and experimental strategies for neuroprotection. Neurol Res. 2008 Dec;30(10):999-1011. doi: 10.1179/174313208X362479. PMID: 19079974.

- Buitenhuis SM, Pondaag W, Wolterbeek R, Malessy MJA. Sensibility of the Hand in Children With Conservatively or Surgically Treated Upper Neonatal Brachial Plexus Lesion. Pediatr Neurol. 2018 Sep;86:57-62. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.04.006. Epub 2018 May 11. PMID: 30077550.

- Elhassan B, Bishop A, Shin A, Spinner R. Shoulder tendon transfer options for adult patients with brachial plexus injury. J Hand Surg Am. 2010 Jul;35(7):1211-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.05.001. PMID: 20610066.

- Tse R, Kozin SH, Malessy MJ, Clarke HM. International Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand Committee report: the role of nerve transfers in the treatment of neonatal brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2015 Jun;40(6):1246-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.01.027. Epub 2015 May 1. PMID: 25936735.