Summary Card

Overview

A congenital defect of the primary palate caused by incomplete embryologic fusion.

Aetiology

Genetic and environmental factors, including maternal behaviors, nutritional deficiencies.

Embryology

Failure of the medial nasal and maxillary processes to fuse during weeks 4–7 of embryonic development.

Anatomy

Disruption of the lip, nasal floor, and maxilla, affecting landmarks like Cupid’s bow, vermilion, and white roll.

Classification

Classified by laterality, extent, and associated anomalies, using standardized systems, such as Veau or LAHSAL.

Clinical Features

Unilateral clefts cause nasal asymmetry & vermilion disruption. Bilateral clefts have absent philtral landmarks and broad nasal tip.

Surgical Repair

Performed at ~6 months; common techniques include Millard’s rotation advancement and Fisher’s subunit repair

Primary Contributor: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow

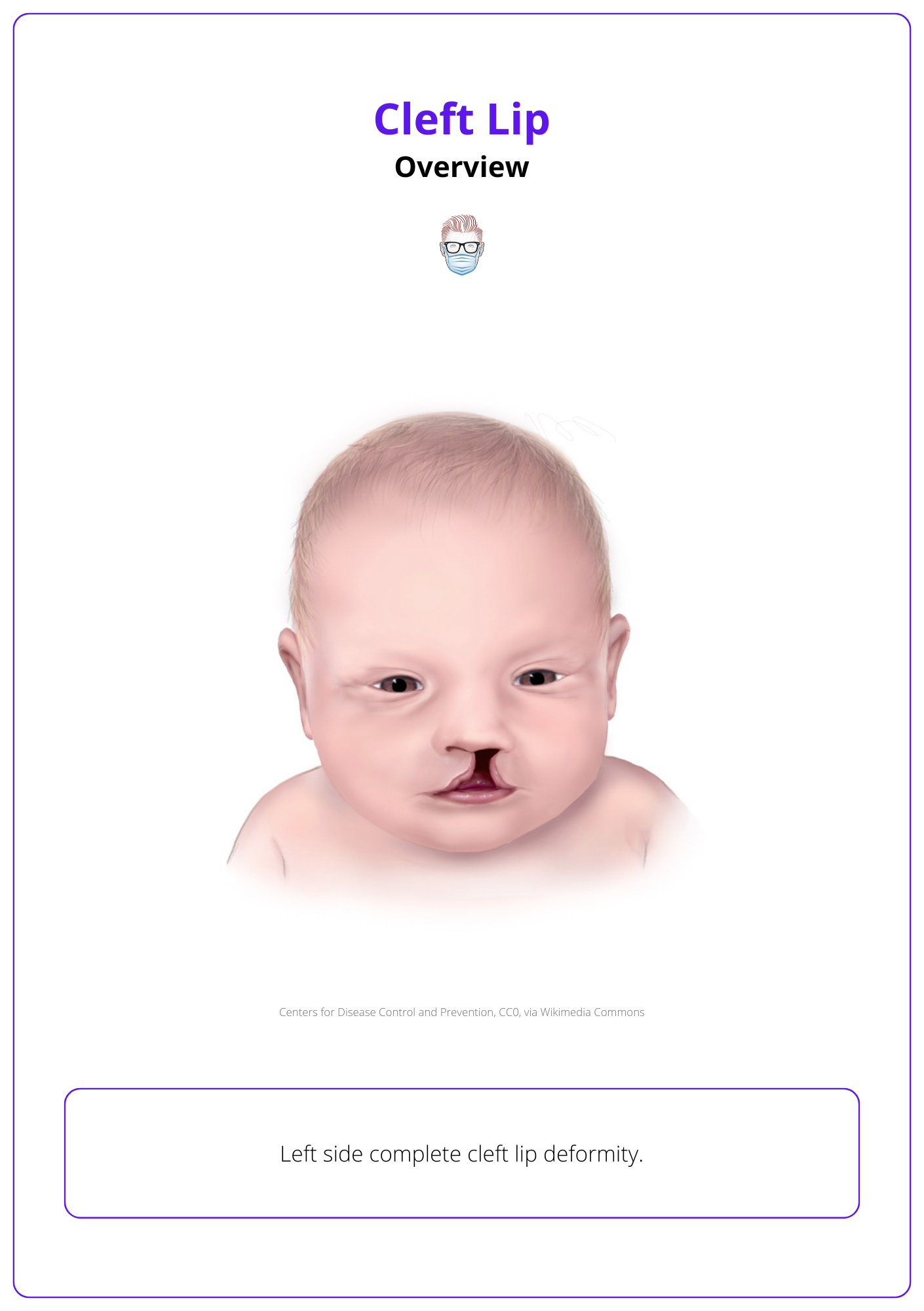

Overview of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip is a common congenital anomaly caused by incomplete fusion of embryologic structures. Genetic and environmental factors contribute to its formation.

A cleft lip is a congenital malformation of the primary palate (lip, alveolus and hard palate anterior to the incisive foramen). It may be complete or incomplete, bilateral or unilateral, syndromic and non-syndromic.

It is caused by incomplete embryological fusion during facial development. Below is an illustration of a left-side complete cleft lip deformity.

Aetiology of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip results from genetic and environmental factors, often linked to maternal behaviors, nutritional deficiencies, and associated syndromes.

The development of a cleft lip is influenced by genetic and environmental factors, including family history, maternal behaviors, and teratogenic exposures.

Genetic Factors

- Genes: Multifactorial genetic inheritance, such as MSX1 and TBX22 (Zhang, 2017).

- Ethnicity: high in Asians, low in African Americans (Shaye, 2015).

- Gender: Males predominate in cleft lip ± palate; females in isolated cleft palate.

Environmental Factors

- Maternal Smoking: Strongly associated, contributing to up to 20% of cases.

- Alcohol Consumption: Correlated with increased risk.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Folic acid deficiency is a notable contributor to cleft formation.

- Teratogenic Exposures: Linked to medications like phenytoin, retinoic acid, anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids.

- Maternal Age: Higher risk in mothers younger than 20 or older than 39 years (Shaye, 2015; Tse, 2013).

Associated Anomalies

Approximately 29% of clefts are linked to other anomalies or syndromes:

- Van der Woude Syndrome: Caused by IRF6 gene mutations, characterized by cleft lip/palate and lower lip pits.

- 22q11 Deletion Syndrome (DiGeorge Syndrome): Associated with cleft palate ± cleft lip, cardiac defects, thymic hypoplasia, and hypocalcemia due to parathyroid hypoplasia (Tijare, 2012).

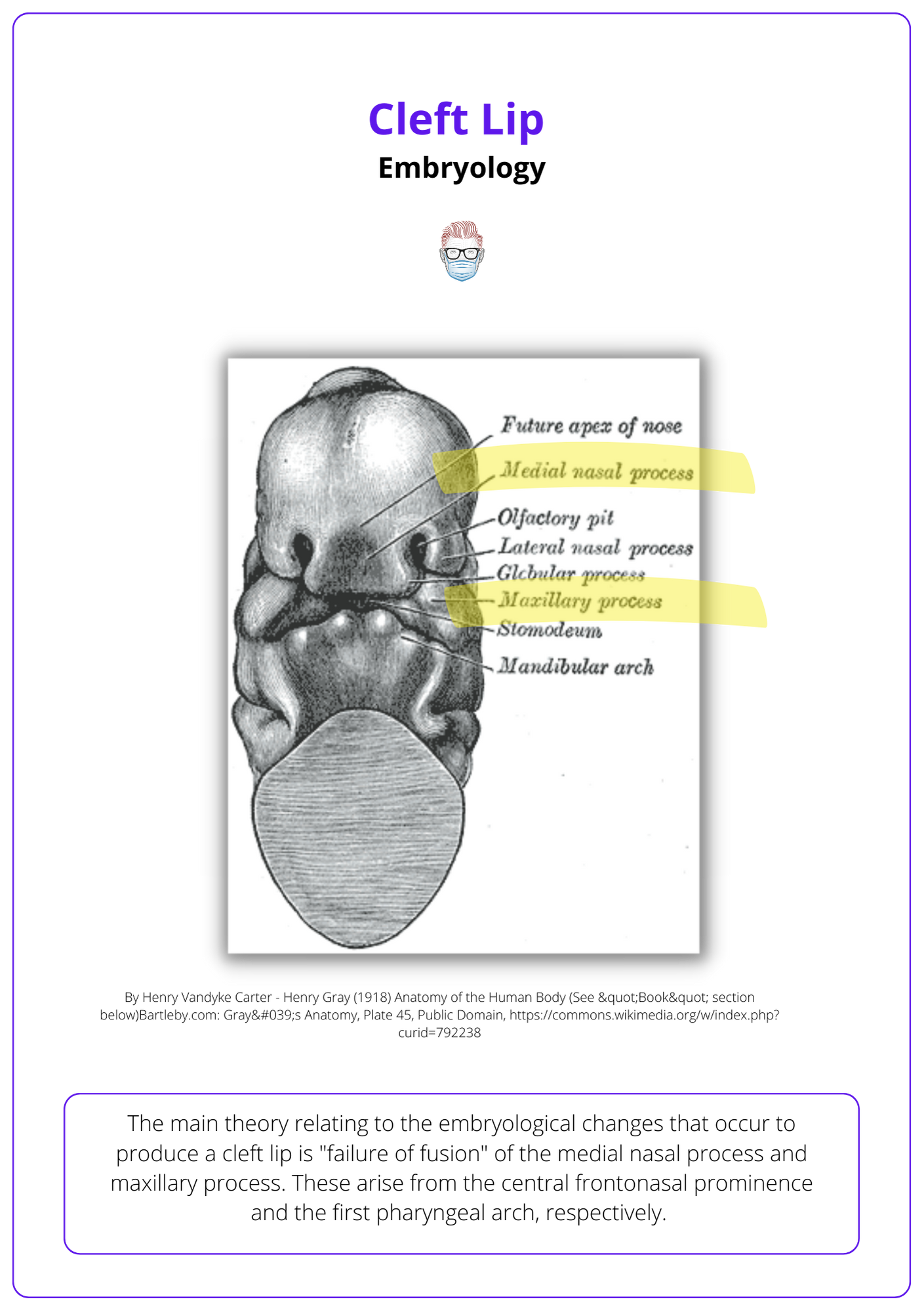

Embryology of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip results from the failure of the medial nasal and maxillary processes to fuse during weeks 4–7 of embryonic development.

Cleft lip arises from disruptions in the fusion of facial primordia, specifically the medial nasal and maxillary prominences, during weeks 4–7 of development. Failure of this fusion results in cleft lip (Smarius, 2017).

- Unilateral Cleft: failure of one maxillary prominence to fuse with the medial nasal prominence.

- Bilateral Cleft: both maxillary prominences fail to fuse with the medial nasal prominence.

Normal Developmental Process

- Week 3: Neural crest cells migrate into the frontonasal and visceral arch regions, forming five facial primordia (frontonasal, maxillary, and mandibular prominences).

- Week 4: Facial prominences form around the stomodeum; nasal prominences develop from mesenchymal proliferation around nasal placodes.

- Weeks 5–6: Medial nasal prominences merge to form the philtrum; maxillary prominences fuse with lateral nasal prominences, shaping the cheek and lateral nose.

- Weeks 7–8: Maxillary prominences fuse with nasal prominences, forming the upper lip

Anatomy of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip disrupts the lip, nasal floor, and maxilla, affecting key neurovascular and muscular structures, as well as defining anatomical landmarks crucial for surgical repair.

Cleft lip involves the loss of continuity in the skin, muscle, and mucosa of the lip, along with displacement of associated structures like the nasal septum and columella.

Anatomy of the Lip

The lip is a complex structure composed of skin, fat, muscle, and mucosa, supported by essential neurovascular elements and muscular architecture.

Musculature

- Primary Muscle: Orbicularis oris, responsible for lip movement and forming the philtrum.

- Other Muscles: Include elevators (e.g., levator labii superioris) and depressors (e.g., depressor anguli oris).

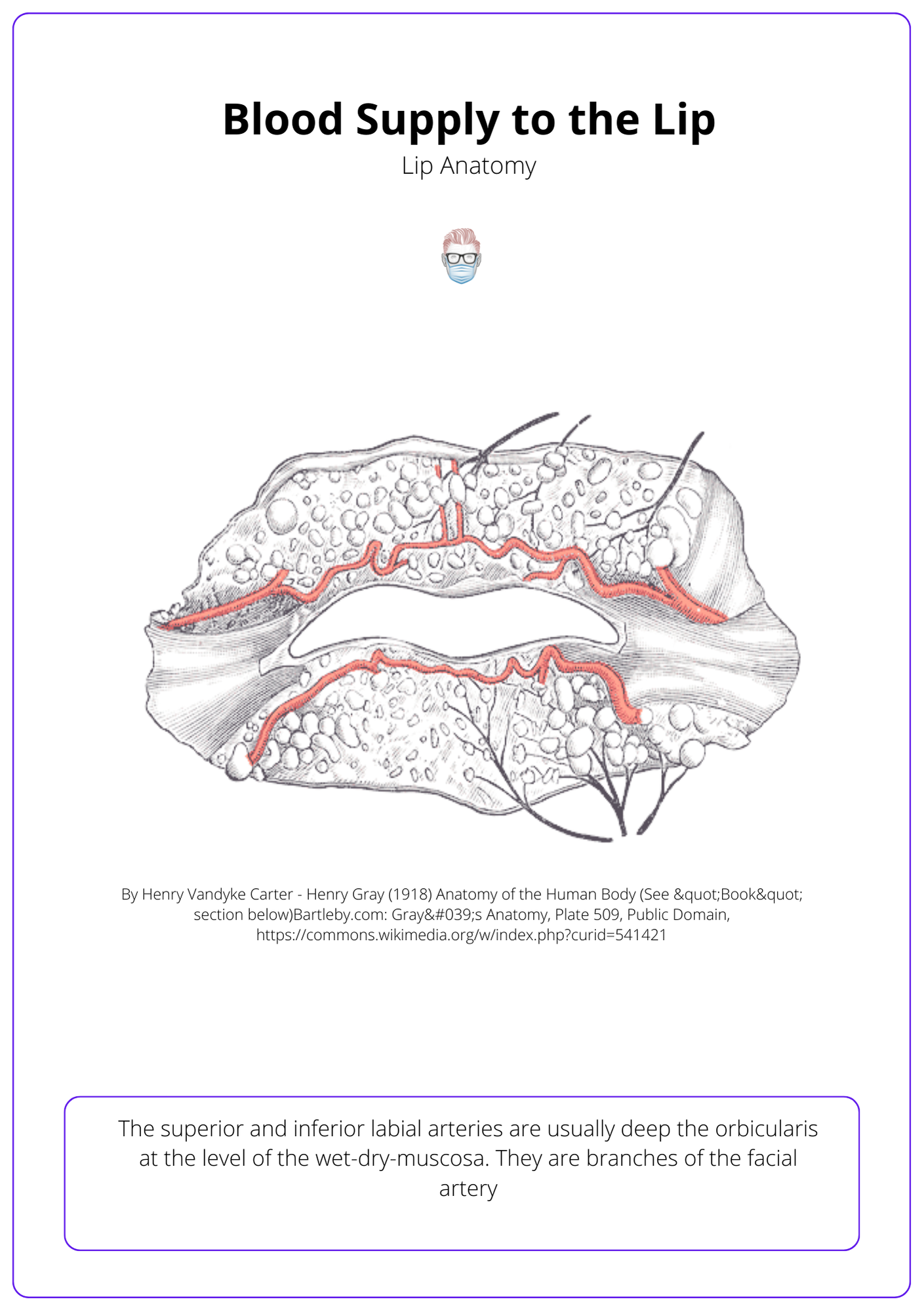

Neurovascular Structures

- Motor: Buccal and mandibular branches of the facial nerve.

- Sensory: Infraorbital (upper lip) and mental (lower lip) branches of the trigeminal nerve.

- Blood Supply: The superior labial artery, a branch of the facial artery, is critical in cleft lip patients as it gives rise to the columellar arteries (Thomas, 2013). This is illustrated below.

The orbicularis oris muscle is made up of three distinct parts, including fibers that decussate at the midline and contribute to speech and expressions.

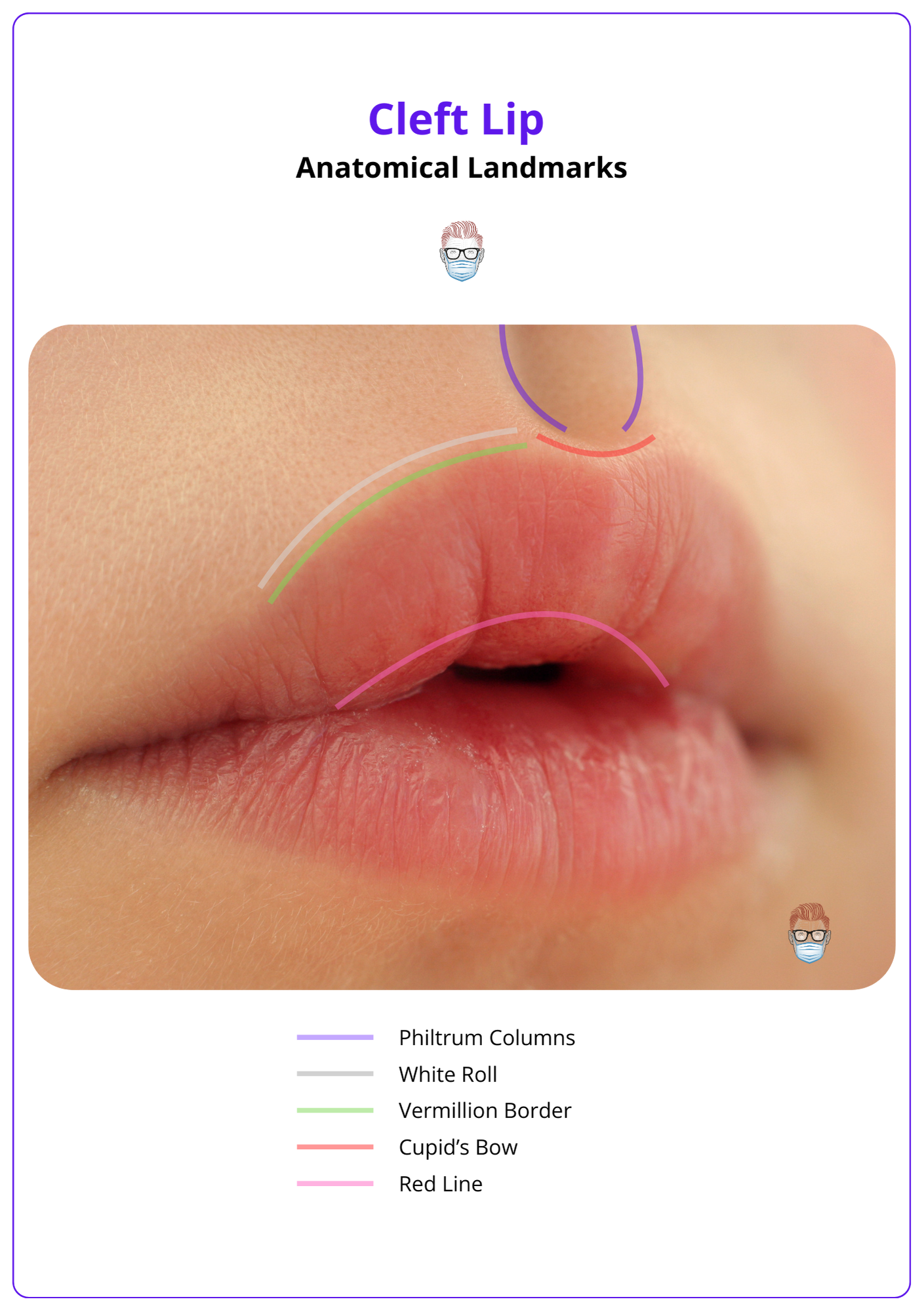

Key Landmarks in Cleft Lip

Cleft lip alters normal lip landmarks, resulting in characteristic disruptions:

- Philtral Columns & Dimple: Bilateral vertical ridges formed by the dermal insertions of the orbicularis oris muscle, with the central philtral dimple created by the decussation of these fibers.

- White Roll: A prominent ridge above the cutaneous–vermilion border. This is the insert point of the Levator Labii Superioris, which elevates the lip and supports Cupid’s bow peaks.

- Cupid’s Bow: The central curve of the white roll, with its peaks aligning with the philtral columns.

- Tubercle: The central fullness of the vermilion at the apex of Cupid’s bow.

- Vermilion: Comprising both the dry (keratinized) and wet (non-keratinized) portions, the vermilion is widest at Cupid’s bow. The red line marks the junction between the dry and wet areas.

These key landmarks in cleft lip are illustrated below.

A slight notch in the vermilion may be the only sign of an incomplete cleft.

Classification of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip is classified based on its laterality, extent, and associated anomalies, with multiple systems providing standardized frameworks for description.

Classifying cleft lip is essential for accurate communication, documentation, and surgical planning. While established classification systems are widely used, a descriptive approach can provide a straightforward and practical assessment of each case.

Descriptive Classification

A practical method to describe cleft lip is by detailing observable features:

- Laterality: Unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral is more common (Tse, 2013).

- Extent: Complete (extending through the lip, nasal floor, and alveolus) or incomplete (partial cleft without reaching the nasal floor).

- Associated Features: Presence of a cleft palate, submucous cleft, or other craniofacial anomalies.

- Syndromic vs. Non-Syndromic: Indicating whether the cleft is part of a syndrome (e.g., Van der Woude syndrome) or isolated.

There is also a microform variant with a furrowed philtrum & vermilion notching (Shkoukani, 2013).

Standardised Classification Systems

Veau Classification: Groups cleft lip and palate into four categories:

- Group 1: Soft palate only.

- Group 2: Hard and soft palate.

- Group 3: Palate extending to the alveolus.

- Group 4: Complete bilateral clefts.

LAHSHAL System:

- Lip, Alveolus, Hard Palate, Soft Palate are labeled from right to left, using capital letters for complete clefts and lowercase for incomplete.

- It classifies clefts by facial region: L (lip), A (alveolus), H (hard palate), S (soft palate), with uppercase for complete clefts, lowercase for incomplete, and "_" for none (Shah, 2011).

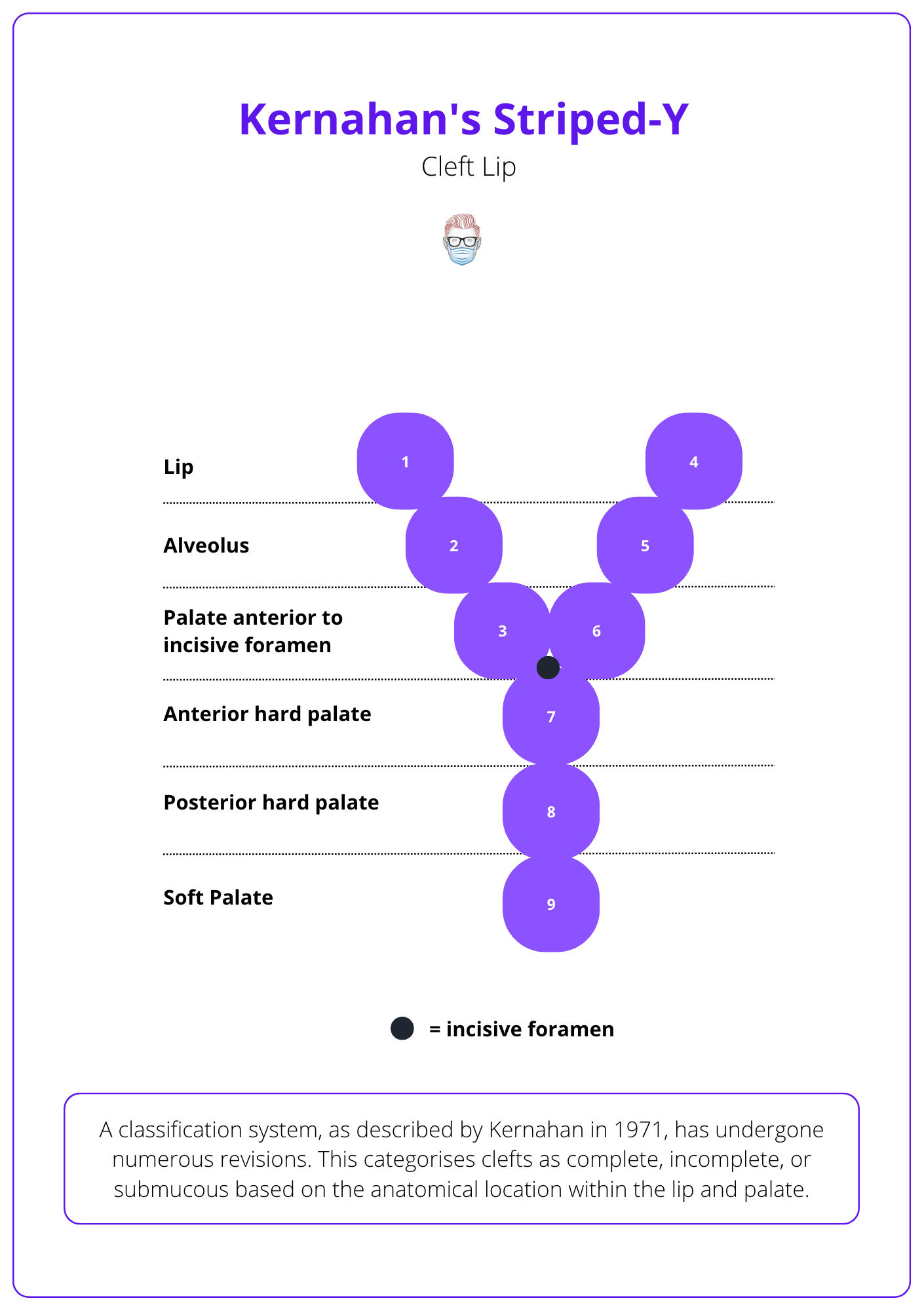

Kernahan Striped-Y Diagram:

- A visual classification system numbered 1–9, representing specific anatomical regions of the lip, alveolus, and palate. This method is often used in surgical planning and research.

This classification system is visualised below

Prenatal diagnosis of cleft lip is possible through second-trimester ultrasound, with detection rates of 60–90% (Smarius, 2017).

Clinical Features of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip causes distinctive disruptions in the lip and nose, with severity influenced by laterality, completeness, and associated anomalies.

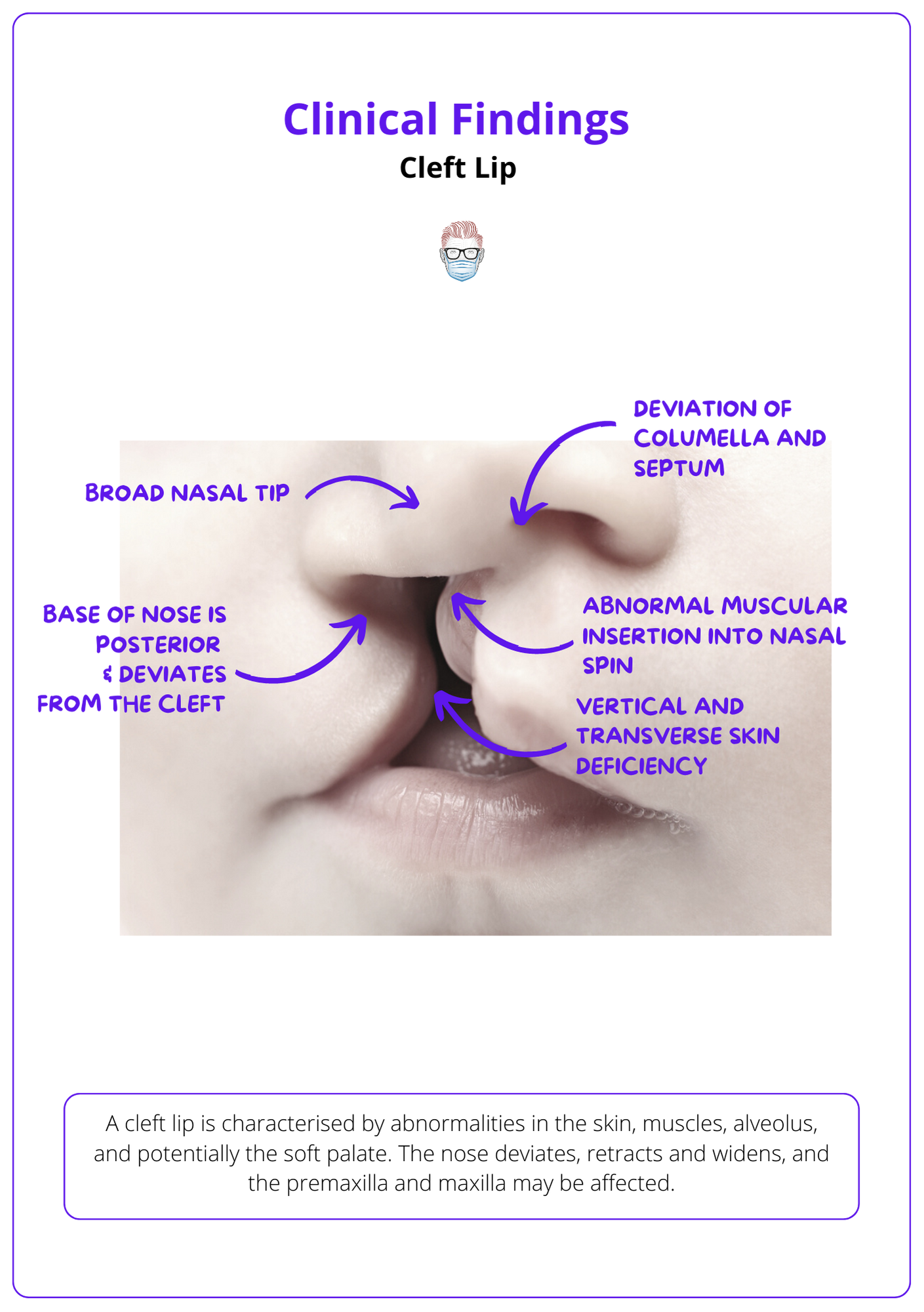

Cleft Lip deformities arise from incomplete fusion of embryological structures, leading to discontinuities in the skin, abnormal muscle attachments, and misalignment of nasal and bony structures.

The Lip

Cleft lip deformities include muscle misalignment, vermilion deficiency, and alveolar gapping.

- Skin: Vertical and transverse deficiencies with discontinuity.

- Muscle: Abnormal insertions into the alar base and nasal spine pulls the alar base laterally and alters lip symmetry. This disrupts the philtrum, which is normally formed by the crossing of orbicularis oris fibers.

- Vermilion Deficiency and White Roll disruption

- Alveolus: Gapping that often extends into the hard palate.

The Nose

Cleft lip affects nasal structure and symmetry, causing septal deviation, broadening of the nasal tip, and misalignment of cartilage.

- Columella and Septum: Deviated posteriorly and away from the cleft, with dislocation from the vomer groove.

- Nasal Tip: Broad and flattened due to separation of alar domes and sagging/kinking of the lateral crus.

- Cartilage and Bones: Sagging of the lateral crus, separation of upper and lower lateral cartilages and flattened nasal bones.

These clinical features are illustrated below

Nordhoff's point, 2 mm above the white roll on the non-cleft side, guides Cupid's bow reconstruction during cleft lip repair, ensuring symmetry - its where the vermillion height is at its greatest (Tse, 2012).

Deformities by Cleft Type

Cleft lip deformities differ significantly between unilateral and bilateral presentations, with unique patterns affecting lip continuity, nasal alignment, and structural displacement.

Unilateral Cleft: Unilateral cleft lips are characterized by asymmetry in both the lip and nose, with disruptions more pronounced on the cleft side.

- Lip:

- Asymmetric vermilion with disrupted white roll (Vyas, 2014).

- Shortened columella and philtral ridge.

- Outward rotation of the medial maxillary segment, causing misalignment of the dental arch.

- Nose:

- Flattened nasal tip with asymmetric nostrils.

- Lateral displacement of the alar base and deviation of the nasal septum toward the non-cleft side.

- Broad nasal tip caused by separated alar domes and flattened lateral cartilages.

Bilateral Cleft: Bilateral cleft lips involve significant disruption of midline structures, leading to central protrusion and bilateral nasal deformities.

- Lip:

- Protruding premaxilla due to lack of attachment to the palatal shelves.

- Absent philtral landmarks, with flattened vermilion

- Prolabium lacks muscle and has an indistinct white roll.

- Nose:

Additional Features to Assess

Cleft lip is often accompanied by additional anomalies that provide clues for syndromic associations or the cleft’s overall severity.

- Palate: Confirm anterior defect to the incisive foramen; ensure no involvement of the soft palate.

- Secondary Features: Lower lip pitting, often seen in syndromic cases like Van der Woude syndrome.

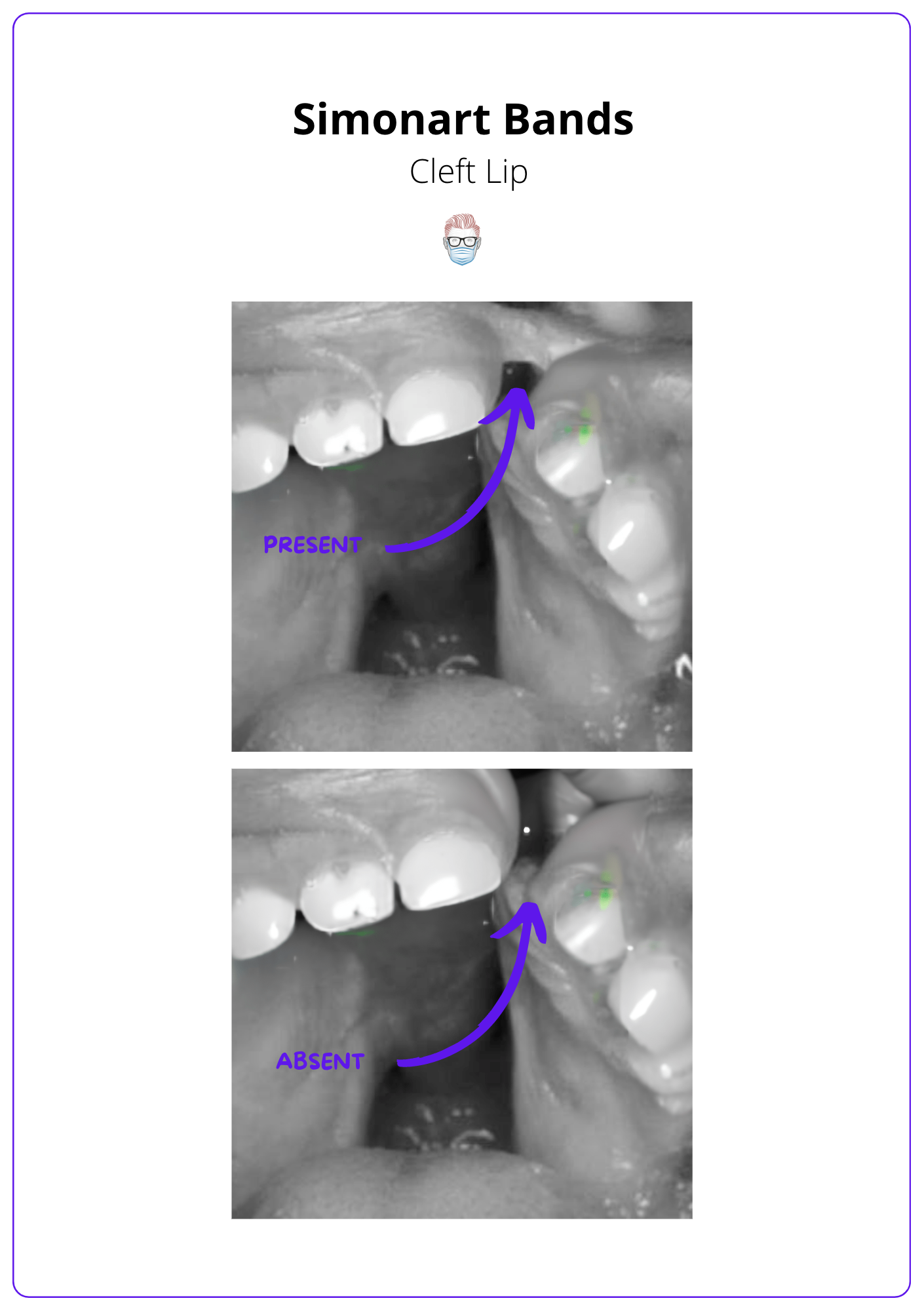

- Simonart Band: a fibrous tissue bridge that may partially connect the edges of a cleft lip or palate. It does not contain any muscle and does not convert a complete into an incomplete cleft lip.

Surgical Repair of Cleft Lip

Cleft lip repair restores facial symmetry and function by reconstructing the orbicularis oris and aligning nasal structures. Timing and technique selection are crucial for optimal outcomes.

Multiple techniques have been described in the repair of unilateral and bilateral cleft lip repair, each with their advantages and disadvantages. The primary goals of cleft lip repair are:

- Achieving symmetry in the lip and nasal structures.

- Restoring a functional orbicularis oris for feeding and speech.

- Correcting nasal alignment to improve airflow and aesthetics.

Timing Cleft Lip Repair

Surgical timing is at the discretion of the cleft surgical team and the anaesthetist. The decision is is based on developmental needs and surgical/anesthetic safety.

It is typically performed at 3–6 months of age and ideally completed by 12 months to support feeding, speech, and facial growth (Slator, 2020). It has traditionally been guided by the Rule of 10s:

- Hemoglobin >10 g/dL

- Weight >10 lbs

- Age >10 weeks.

Techniques for Cleft Lip Repair

Fisher Subunit Repair:

- Technique: Aligns aesthetic subunits of the lip for natural contour and symmetry. 25 points can be marked using callipers on the medial lip, nasal floor and lateral lip, as outlined in the initial PRS publication in 2005.

- Benefits: Superior cosmetic outcomes; increasingly preferred over Millard’s technique.

Millard’s Rotation-Advancement Technique:

- Technique: A triangular flap from the upper lip is rotated and advanced to reconstruct the philtrum (Shaye, 2015).

- Benefits: Versatile and allows intraoperative adjustments. Simplifies future revisions.

- Limitations: May result in nasal base scarring or vertical lip deficiency.

Tennison-Randall Geometric Repair:

- Technique: Uses triangular flaps and Z-plasty to achieve tension-free closure.

- Benefits: Effective at restoring tension balance across the lip.

- Limitations: Difficult to adjust intraoperatively; does not restore philtral column.

Mohler Modification:

- Technique: Preserves and reconstructs the philtral column by modifying Millard’s approach

- Benefits: Superior philtral symmetry and aesthetics (Vyas, 2014)

Millard and Mulliken Techniques:

- Primarily used for bilateral cleft lip cases, addressing the central prolabium and lateral lip segments. Challenges include a protruding premaxilla and absent orbicularis oris in the prolabium (Zhang, 2017).

- Single-Stage Repair: Combines lip and nasal repair in one procedure.

- Staged Repair: Lip repair is performed first, with columellar lengthening at 1–5 years.

Additional Considerations

- Lip Adhesion can be indicated for wide clefts or bilateral clefts with a protruding premaxilla. It converts a wide cleft into a less challenging incomplete cleft for definitive repair.

- Bone Grafting can be performed at 10 years of age during mixed dentition to support permanent canine eruption. It Involves:

- Preparation: Raising gingivoperiosteal flaps and closing the nasal mucosa.

- Harvesting: Cancellous bone from the iliac crest.

- Insertion: Packing the graft into the defect and closing the oral mucosa.

- Pre-Surgical Orthodontics has Limited evidence supports its use, and it adds a significant burden of care. Key points:

- Uses passive or dynamic appliances to narrow the cleft, align the alveolus, and mold the nasal deformity.

- Aims to ease surgical repair and improve outcomes but may inhibit growth, raising concerns about long-term effects

- Primary Nasal Correction is performed during primary lip repair to reposition the alar cartilage and improve nasal symmetry. It is considered in wide clefts using a limited McComb technique, which involves:

- Dorsal supra-cartilaginous dissection.

- Separation of cleft alar cartilage from the piriform aperture.

- Percutaneous sutures and bolsters to lift the cartilage into the correct position.

- Secondary Rhinoplasty typically performed in adolescence after nasal and midfacial growth is complete. Addresses persistent deformities such as deviated septum, shortened columella, and tip asymmetry (Sykes, 2016).

Complications Cleft Lip Repair

Cleft lip repair involves both immediate and long-term risks that can impact surgical outcomes and patient quality of life:

- Immediate Risks: Wound dehiscence, infection, hematoma formation.

- Long-Term Risks: Asymmetric scarring, Persistent nasal deformities, Maxillary hypoplasia affecting facial growth, Speech and feeding difficulties (Shaye, 2015).

Intrauterine repair, although possible, is not recommended in view of the risk of inducing preterm labour, and is reserved for conditions deemed fatal if not corrected prior to delivery.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Cleft lip is a congenital craniofacial anomaly caused by incomplete fusion of embryologic structures, requiring a multidisciplinary approach for functional and aesthetic management.

2. Epidemiology and Aetiology: Cleft lip is more common in males, with left-sided clefts being the most frequent. Genetic and environmental factors, like smoking and folic acid deficiency, contribute to development.

3. Embryology and Classification: Failure of medial nasal processes and maxillary prominences fusion during weeks 4–7 leads to cleft lip. It is classified by laterality and completeness.

4. Clinical Features and Repair: Deformities affect the lip and nose, with more severe bilateral cases. Surgical repair aims to restore symmetry and function, using techniques like Millard’s and Fisher’s subunit repair.

Further Reading

- Shkoukani, Mahdi A., Michael Chen, and Angela Vong. "Cleft lip–a comprehensive review." Frontiers in pediatrics 1 (2013): 53.

- Slator, Rona, et al. "Range and timing of surgery, and surgical sequences used, in primary repair of complete unilateral cleft lip and palate: the cleft care UK study." Orthodontics & Craniofacial Research 23.2 (2020): 166-173.

- Shaye, David, C. Carrie Liu, and Travis T. Tollefson. "Cleft lip and palate: An evidence-based review." Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics 23.3 (2015): 357-372.

- Yılmaz HN, Özbilen EÖ, Üstün T. The Prevalence of Cleft Lip and Palate Patients: A Single-Center Experience for 17 Years. Turk J Orthod. 2019 Sep;32(3):139-144. doi: 10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2019.18094. Epub 2019 Sep 1. PMID: 31565688; PMCID: PMC6756567.

- Zhang, Jacques X., and Jugpal S. Arneja. "Evidence-based medicine: the bilateral cleft lip repair." Plastic and reconstructive surgery 140.1 (2017): 152e-165e.

- Tijare, Manisha, et al. "Syndrome associated with cleft palate and cleft lip." Indian Journal of Dental Advancements 4.3 (2012): 920-926.

- Tse, Raymond. "Unilateral cleft lip: principles and practice of surgical management." Seminars in plastic surgery. Vol. 26. No. 04. Thieme Medical Publishers, 2012.

- Smarius, Bram, et al. "Accurate diagnosis of prenatal cleft lip/palate by understanding the embryology." World journal of methodology 7.3 (2017): 93.

- Thomas, Marc D., et al. "Normal nasolabial anatomy in infants younger than 1 year of age." Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 131.4 (2013): 574e-581e.

- Shah, Syed Nasir, Mariya Khalid, and Muhammad Sartaj Khan. "A review of classification systems for cleft lip and palate patients-I. morphological classifications." Journal of Khyber College of Dentistry 1.02 (2011): 95-99.

- Vyas, Raj M., and Stephen M. Warren. "Unilateral cleft lip repair." Clinics in plastic surgery 41.2 (2014): 165-177.

- Sykes, Jonathan M., Abel-Jan Tasman, and Gustavo A. Suárez. "Cleft Lip Nose." Clinics in plastic surgery 43.1 (2016): 223-235.