Contributing Authors: Bryce Stash MD, Natalie Gaio, MD. Verified by thePlasticsFella

In this Article

5 Key Points

1. What is Carpal Tunnel Syndrome?

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome is a compression neuropathy of the median nerve as it travels under the transverse carpal ligament.

2. What are the borders of Carpal Tunnel?

- Floor: proximal carpal row

- Roof: transverse carpal ligament

- Ulnar: hook of hamate and pisiform

- Radial: Scaphoid tubercle and trapzium

3. What causes Carpal Tunnel Syndrome?

Compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. It is associated with

diabetes, hypothyroidism, obesity, pregnancy, and rheumatoid arthritis.

4. What are the signs and symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome?

A clinical diagnosis of paresthesias in the median nerve distribution, waking up at night and flicking the hand, thenar muscle wasting (severe). This can be supported by Nerve Conduction Studies.

5. What are treatment options for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome?

- Non-operative: NSAIDS, splinting, activity modifications.

- Steroid Injection

- Carpal Tunnel Release

Definition of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Carpal Tunnnel Syndrome is compressive neuropathy of the median nerve as it travels through the carpal tunnel. To put the condition into context:

- It affects approximately 4% of the adults in the United States.1

- Women are affected 3-5x more often than men.2

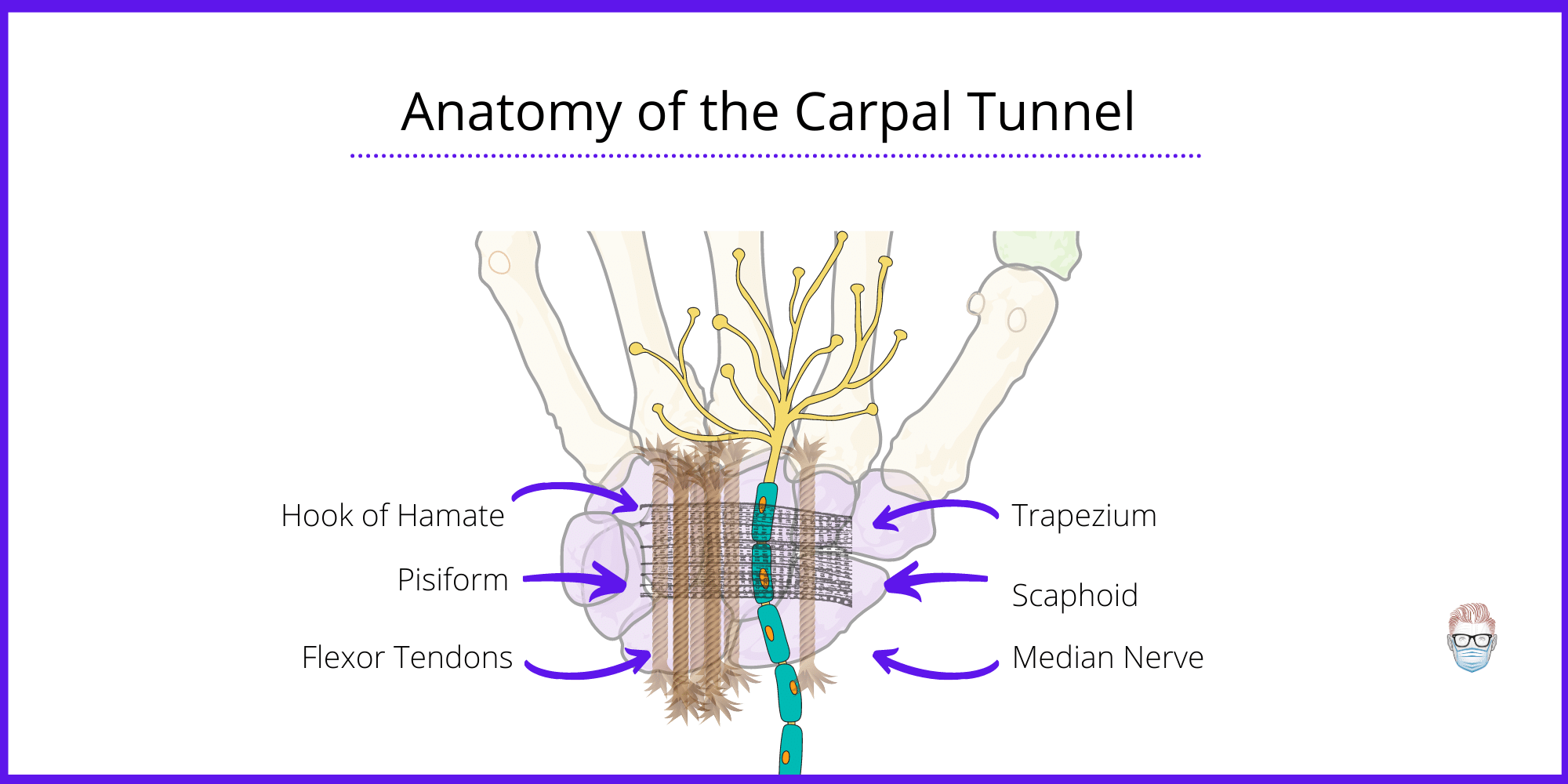

Anatomy of the Carpal Tunnel

The carpal tunnel is a osseo-fibrous structure through which the median nerve and 9 flexor tendons travel.

Boundaries

The carpal tunnel has well-defined anatomical boundaries.

- Roof: Transverse carpal ligament with 4 bony insertions, which creates 2 walls.

- Radial Wall: scaphoid tubercle and trapezium

- Ulnar Wall: hamate and pisiform.

Contents

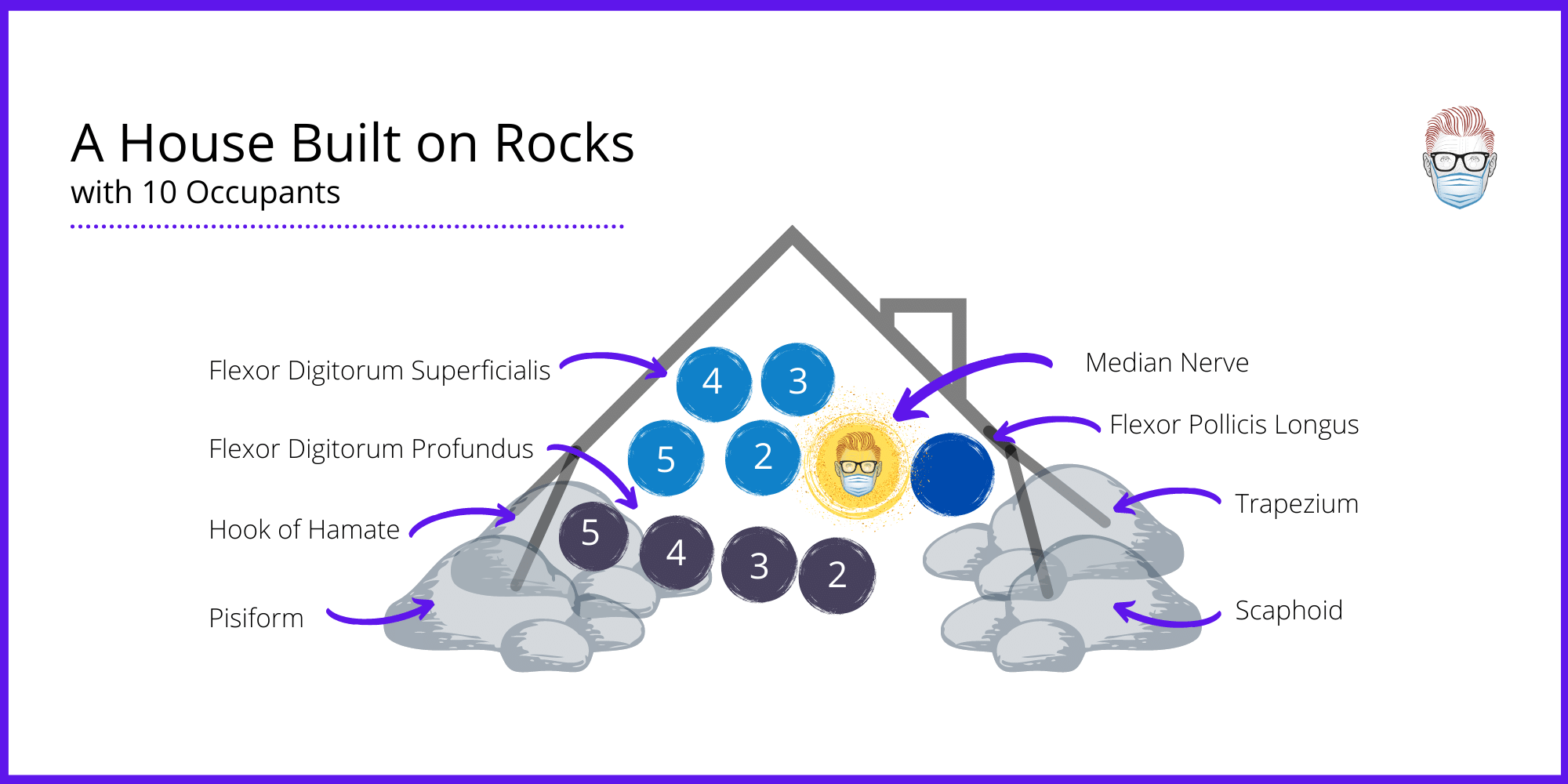

Ten structures pass through the carpal tunnel. An easy memory hook/mnemonic is that carpal tunnel is a house - it has a roof (TCL) with rock walls (carpal bones). Inside this house, there are 10 occupants. This includes:

- Flexor digitorum profundus (4 tendons)

- Flexor digitorum superficialis (4 tendons)

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Median nerve.

The numbers of the tendon relate to which finger they provide function. For example, FDS 2 and FDP 2 are the flexor tendons of the index finger.

Important Branches

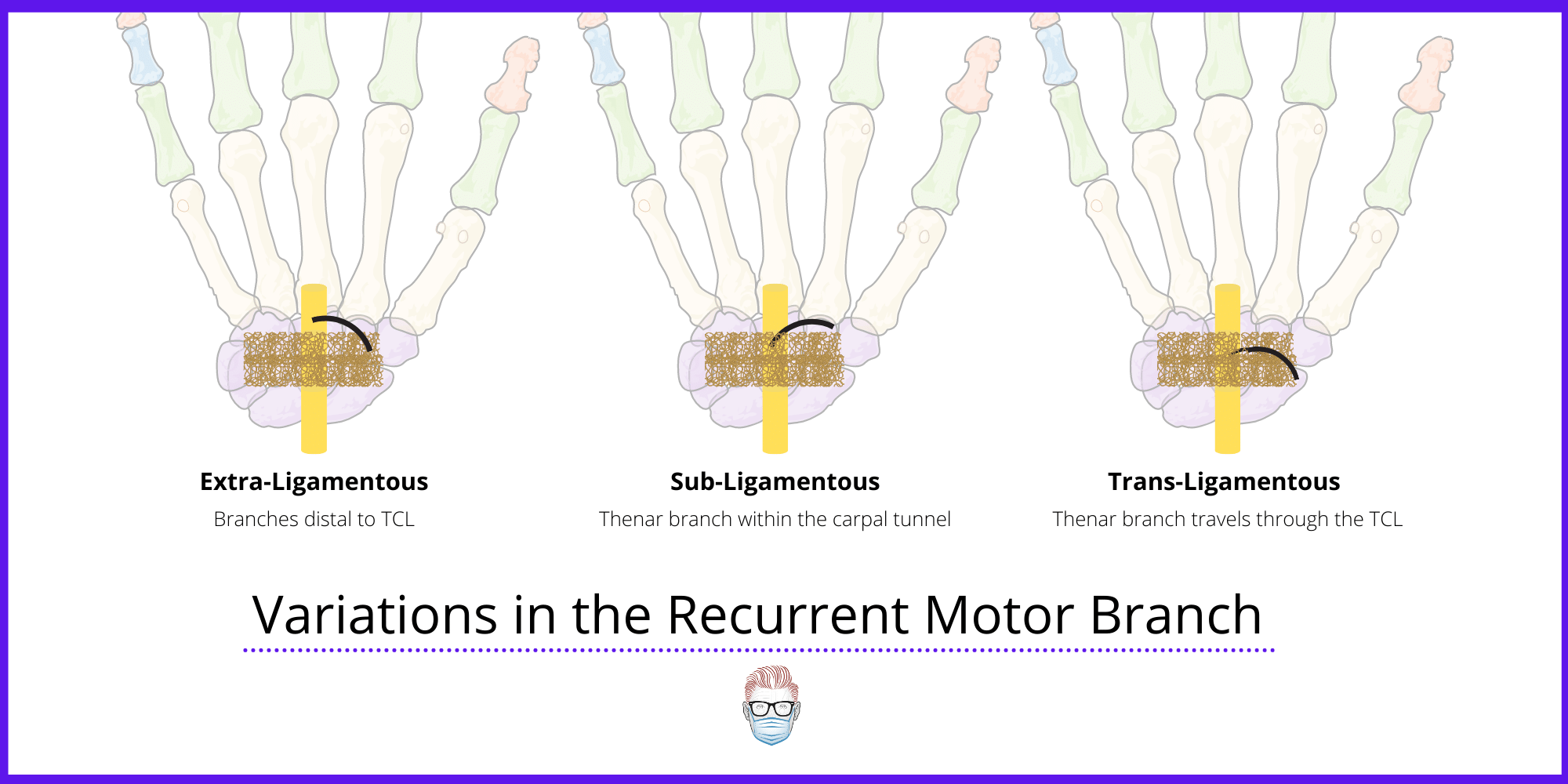

There are two important median nerve branches to be aware of in relation to the carpal tunnel syndrome.

Palmar Cutaneous Branch provides sensation to the palm of the hand. This is not affected in carpal tunnel syndrome because it branches ~ 5cm before the carpal tunnel. To avoid iatrogenic injury, some surgeons incise ulnar to the axis of the flexed ring finger.

Recurrent Motor Branch provides motor innervation to the thenar muscles. Anatomic variation can lead to iatrogenic injury during Carpal Tunnel Release. The anatomical varations of this branch can be classified by Lanz in 1977.

- Extra-Ligamentous (46-90%)

- Subligamentous (31%)

- Transligamentous (23%)

The true incidence of these variations is equivocal3. In the same paper in 1977, Lanz also classified median nerve varations into 4 groups:

- Variations in course of thenar branch (as above)

- Accessory branches of the median nerve at the distal carpal tunnel.

- High division of the median nerve.

- Accessory branches proximal to the carpel tunnel.

This is discussed in more detail in P'Fella's journal club analysis here

On a side note, it is an important landmark for flexor/volar zones of the hand. The carpal tunnel represents "zone 4".

Causes of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome is caused by an increase in size of the tunnel contents or a decrease in size of the tunnel. This shift from the normal causes a commpressive neuropathy of the median nerve.

The aetiology of carpal tunnel syndrome is multifaceted, including diseases/conditions which may either decrease the size of the carpal tunnel or increase the size of the contents within the carpal tunnel. A decrease in the size of the carpal tunnel may be caused by conditions such as mechanical overuse (most common), trauma, or osteoarthritis. Conditions increasing the size of the contents within the carpal tunnel may include mass/tumors (ex. Ganglion cyst) or synovial hypertrophy such as in rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnosing Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis based on a combination of symptoms and characteristic physical findings; its presence may be subsequently confirmed with electrodiagnostic studies.

Symptoms of Carpal Tunnel

Patients with Capral Tunnel syndrome can have sensory and motor symptoms. These symptoms include:

- Paresthesia, often nocturnal, in radial 3 1/2 digits

- Paresthesias in “fixed wrist activities” such as reading a book or a newspaper.

- Aching in thenar eminence43.

- Weakness/atrophy of abductor pollicis brevis (solely innervated by the median nerve)44,49

Provocative Tests

There are multiple provocative tests available for evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome, all with varying sensitivities and specificities.4-7 Positive tests will reproduce the patient’s symptoms. This is summarised below.

Phalen's test

- Flexes the patient’s wrist, holding this position for 60 seconds

- Sensitivity 68-70%, Specificity 73-83%

Tinel’s test

- Tap patient’s volar wrist over the volar carpal tunnel

- Sensitivity 20-50%, Specificity 76-77%

Durkan’s test

- Press thumbs over the patient’s carpal tunnel for 30 seconds

- Sensitivity 87%, Specificity 90%

A novel test, yet to be widely adopted, is the scratch collapse test41,42

- Medially directed force against resisted external shoulder rotation, lightly scratch the skinover the nerve being examined, and re-apply force.

- elicits a “cutaneous silent period” in skeletal muscle by applying a noxious stimulus over a functionally impaired nerve.

- Mixed results on accuracy compared to Tinel or Phalen test.

Investigations

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. Ancillary tests can be useful when the diagnosis is in question, or when the diagnosis is confounded by other disease processes.8-10 These investigations are listed below.

Electrodiagnostic Studies

- These include Nerve Conduction Studies and Electromyography.

- Most commonly used diagnostic test for evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome6

- Advantages: can help differentiate multiple peripheral nerve disorders, stages the degree of nerve compression, can guide expected median nerve recovery.

- Disadvantages: no more sensitive or specific than physical exam, can be uncomfortable to the patient, expensive 11-13

Imaging

- Ultrasound: non-invasive, rapid, inexpensive method of diagnosing carpal tunnel syndrome, diagnostic criteria includes hypoechoic median nerve cross-sectional area > 10 mm14. It has a sensitivity 82%, Specificity 92%

- MRI: low sensitivity (23-96%) and specificity (39-97%) for detecting carpal tunnel syndrome, expensive, but useful for detecting masses15

- X-Ray: plain films play no role in diagnosis of standard carpal tunnel syndrome

Differential Diagnosis

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome quite often fits the classical clinical history and examination. If that's not the case, the other aetiology to consider is:

Pronator teres syndrome

This is a compressive neuropathy of the median nerve at the elbow that can be differentiated from carpal tunnel by:

- Patients may have aching over the proximal forearm

- Involvement of palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve

- lack characteristic night-time carpal tunnel symptoms

Anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) syndrome

This is a compressive neuropathy of the AIN in the forearm, and differs from carpal tunnel syndrome by:

- lack any sensory deficits

- Weakness in grip and pinch as AIN innervates FPL, PQ, and FDP of the index and middle fingers (patient unable to make A-OK sign)

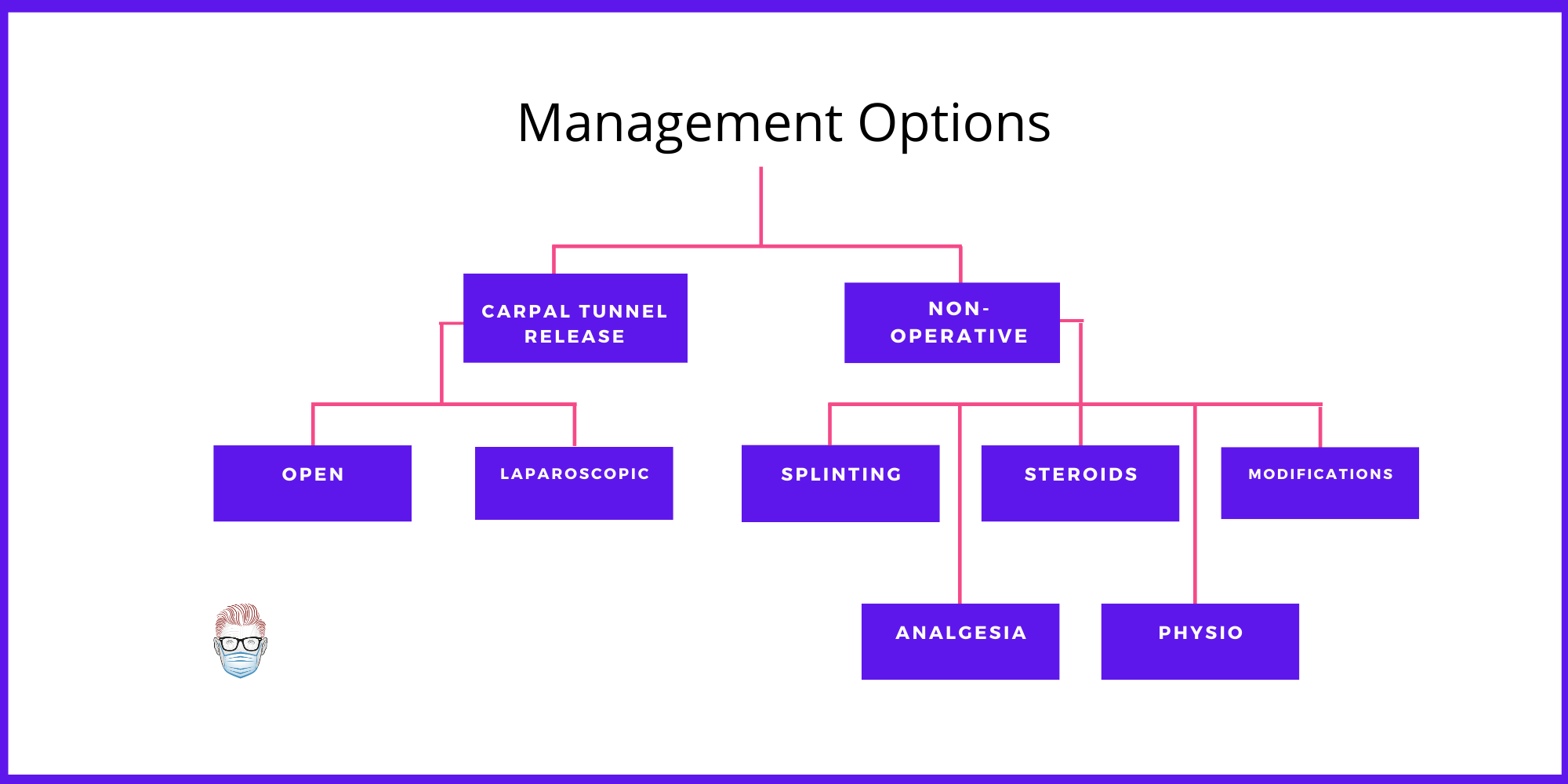

Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Non-Surgical

Conservative management can be considered a suitable option for many patients13,16. These options may include:

- Splinting in neutral

- Anti-inflammatory medications

- Steroid injections

There has been significant research into steroid injections for carpal tunnel syndrome. Some suggest it as a diagnostic tool39, whilst other studies have shown 1/3 of patients do no require further surgical intervention40. Importantly, incom- plete effect of an injection does not, however, predict poor response to surgery46.

Surgical

Two main options exist for surgical decompression of the carpal tunnel: endoscopic and open carpal tunnel releases. Both options have proven to be equally effective long-term17. Endoscopic has increase risk of median nerve injury46, but it's complication rate is still debated51

In terms of open, this can be a limited or standard/extended incision. There are some advocates of a double small incision48.

Generally speaking, an open carpal tunnel release requires the division of the following. Each surgeon has their own preference.

- Skin: longitudinal incision in-line with radial border of ring finger

- Soft-Tissue: fat, palmar fascia +/-palmaris brevis muscle

- Transverse carpal ligament under direct visualization (proximal and distal)

Literature shows that tourniquets can cause significantly more pain with no significant clinical benefit as compared with using a wide awake, no tourniquet approach28

The role for post-operative splinting is controversial. The use and duration of splinting after carpal tunnel release vary widely. This suggests there is limited therapeutic benefit to splinting, which is supported by current literature50

In severe cases, a synevectomy can be performed. Internal neurolysis adds no significant benefit to outcome in routine carpal tunnel release52

Revision Surgery

Revision surgery may be performed when carpal tunnel symptoms persist, carpal tunnel symptoms recur after a symptom-free period, or an iatrogenic injury is suspected.30-32

A systematic review in 2019 has highlighted risk factors for revision carpal tunnel release. These include29:

- Endoscopic release

- Males

- Smokers

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Staged or simultaneous bilateral carpal tunnel release.

Outcomes after revision carpal tunnel release are generally worse than after primary surgery, with notably lower success in alleviating patient symptoms33-36. This is well explained in the video below.

Outcomes

Carpal Tunnel Release is a safe, reproducible surgery with generally excellent results18-21 .

There is data to suggest the following:

- Strength: return of grip to nearly 100% by 3 months, while pinch strength is expected to return to normal levels by 6 weeks.22

- Symptoms: >1 year postoperatively, 2% of patients with moderate and 19% of patients with severe carpal tunnel syndrome report symptoms.23

- Predictors of Poor Outcomes include diabetes, thoracic outlet syndrome, tobacco use, thenar atrophy, and perceived disability.24-27.

Despite the significant increase in the number of randomized controlled trials published studying surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome over time, the quality of the research has not changed overtime - this needs to be improved47.

Bibliography

1. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al.; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35.

2. Miller TT, Reinus WR. Nerve entrapment syndromes of the elbow, forearm, and wrist. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195 (3): 585-94.

3. Kozin S. H. (1998). The anatomy of the recurrent branch of the median nerve. The Journal of hand surgery, 23(5), 852–858. https://doi-org.ezp.slu.edu/10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80162-7

4. Marx RG, Hudak PL, Bombardier C, Graham B, Goldsmith C, Wright JG. The reliability of physical examination for car- pal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:499–502.

5. Lane LB, Starecki M, Olson A, Kohn N. Carpal tunnel syn- drome diagnosis and treatment: A survey of members of the American Society For Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:2181–2187.e4.

6. Deniz FE, Oksüz E, Sarikaya B, et al. Comparison of the diagnostic utility of electromyography, ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome determined by clinical findings. Neurosurgery 2012;70:610–616.

7. Durkan JA. A new diagnostic test for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:535–538.

8. Hentz VR, Lalonde DH. MOC-PS(SM) CME article: Self- assessment and performance in practice. The carpal tunnel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(Suppl):1–10.

9. Lalonde DH. Evidence-based medicine: Carpal tunnel syn- drome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1234–1240.

10. Shores JT, Lee WP. An evidence-based approach to carpel tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:2196–2204.

11. Graham B. The value added by electrodiagnostic testing in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2587–2593.

12. Sears ED, Swiatek PR, Hou H, Chung KC. Utilization of preopera- tive electrodiagnostic studies for carpal tunnel syndrome: An anal- ysis of national practice patterns. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:665–672.

13. D’Arcy CA, McGee S. The rational clinical examination: Does this patient have carpal tunnel syndrome? JAMA 2000;283:3110–3117.

14. Patil P, Dasgupta B. Role of diagnostic ultrasound in the assessment of musculoskeletal diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012;4:341–355.

15. Dong Q, Jacobson JA, Jamadar DA et-al. Entrapment neuropathies in the upper and lower limbs: anatomy and MRI features. Radiol Res Pract. 17;2012: 230679.

16. O’Connor D, Marshall S, Massy-Westropp N. Non-surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD003219.

17. Zuo D, Zhou Z, Wang H, et al. Endoscopic versus open car- pal tunnel release for idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:12.

18. Lee WP, Strickland JW. Safe carpal tunnel release via a limited palmar incision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:418–424; discussion 425–426.

19. Klein RD, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Open carpal tunnel release using a 1-centimeter incision: Technique and outcomes for 104 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1616–1622.

20. Stone OD, Clement ND, Duckworth AD, Jenkins PJ, Annan JD, McEachan JE. Carpal tunnel decompression in the super-elderly: Functional outcome and patient satisfaction are equal to those of their younger counterparts. Bone Joint J. 2014;96:1234–1238.

21. Louie DL, Earp BE, Collins JE, et al. Outcomes of open car- pal tunnel release at a minimum of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1067–1073.

22. Gellman H, Kan D, Gee V, Kuschner SH, Botte MJ. Analysis of pinch and grip strength after carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(5):863-864. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(89)80091-7

23. Kronlage SC, Menendez ME. The benefit of carpal tunnel release in patients with electrophysiologically moderate and severe disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(3):438-44.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.12.012

24. Gong HS, Huh JK, Lee JH, Kim MB, Chung MS, Baek GH. Patients’ preferred and retrospectively perceived levels of involvement during decision-making regarding carpal tun- nel release. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1527–1533.

25. Shifflett GD, Dy CJ, Daluiski A. Carpal tunnel surgery: Patient preferences and predictors for satisfaction. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:685–689.

26. Kadzielski J, Malhotra LR, Zurakowski D, Lee SG, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Evaluation of preoperative expectations and patient satisfaction after carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1783–1788.

27. Turner A, Kimble F, Gulyás K, Ball J. Can the outcome of open carpal tunnel release be predicted? A review of the lit- erature. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:50–54.

28. Olaiya, Oluwatobi, Alagabi, Awwal, Mbuagbaw, Lawrence, McRae, Mark. Carpal Tunnel Release without a Tourniquet: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(3):737-744. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006549.

29. Westenberg, Ritsaart, Oflazoglu, Kamilcan, de Planque, Catherine, Jupiter, Jesse, Eberlin, Kyle, Chen, Neal. Revision Carpal Tunnel Release: Risk Factors and Rate of Secondary Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(5):1204-1214. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006742.

30. Tung TH, Mackinnon SE. Secondary carpal tunnel surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1830-1843

31. Tutz N, Gohritz A, van Schoonhoven J, Lanz U. Revision surgery after carpal tunnel release-Analysis of the pathology in 200 cases during a 2-year period. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:68-71

32. Jones NF, Ahn HC, Eo S. Revision surgery for persistent and recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and for failed carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:683-692

33. Jansen MC, Evers S, Slijper HP, de Haas KP, Smit X, Hovius SE, et al. Predicting clinical outcome after surgical treatment in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:1098-1106.

34. Hulsizer DL, Staebler MP, Weiss AP, Akelman E. The results of revision carpal tunnel release following previous open versus endoscopic surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23:865-869

35. Djerbi I, Cesar M, Lenoir H, Coulet B, Lazerges C, Channas M. Revision surgery for recurrent and persistent carpal tunnel syndrome: Clinical results and factors affecting outcomes. Chir Main. 2015;34:312-317

36. Chang B, Dellon AL. Surgical management of recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:467-470.

37. Keith MW, Masear V, Chung KC, et al; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:218-219.

40. Evers, Stefanie, Bryan, Andrew, Sanders, Thomas, Gunderson, Tina, Gelfman, Russell, Amadio, Peter. Corticosteroid Injections for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Long-Term Follow-Up in a Population-Based Cohort. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(2):338-347. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000003511.

41. Cheng CJ, Mackinnon-Patterson B, Beck JL, Mackinnon SE. Scratch collapse test for evaluation of carpal and cubital tun- nel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1518–1524.

42. Blok RD, Becker SJ, Ring DC. Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: Interobserver reliability of the blinded scratch- collapse test. J Hand Microsurg. 2014;6:5–7.

43. Levine DW, Simmons BP, Koris MJ, et al. A self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1585–1592.

44. D’Arcy CA, McGee S. The rational clinical examination: Does this patient have carpal tunnel syndrome? JAMA 2000;283:3110–3117.

45. Green DP. Diagnostic and therapeutic value of carpal tunnel injection. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9:850–854.

46. Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T, Duku E. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1137–1146.

47. Long, Chao M.D.; Azad, Amee D. B.A.; desJardins-Park, Heather E. A.B.; Fox, Paige M. M.D., Ph.D. Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials for Surgical Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Systematic Review, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: March 2019 - Volume 143 - Issue 3 - p 791-799 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005366

48. Zhang, Xu M.D., Ph.D.; Huang, Xiangye M.D.; Wang, Xianhui M.D.; Wen, Shumin M.D.; Sun, Jianxin M.D.; Shao, Xinzhong M.D. A Randomized Comparison of Double Small, Standard, and Endoscopic Approaches for Carpal Tunnel Release, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: September 2016 - Volume 138 - Issue 3 - p 641-647. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002511

49. Liu, Fan M.D.; Watson, H Kirk M.D.; Carlson, Lois O.T.R./L., C.H.T.; Lown, Ira M.D.; Wollstein, Ronit M.D. Use of Quantitative Abductor Pollicis Brevis Strength Testing in Patients with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: April 1, 2007 - Volume 119 - Issue 4 - p 1277-1283

doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000254498.49588.2d

50. Henry, Steven L. M.D.; Hubbard, Bradley A. M.D.; Concannon, Matthew J. M.D. Splinting after Carpal Tunnel Release: Current Practice, Scientific Evidence, and Trends, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: October 2008 - Volume 122 - Issue 4 - p 1095-1099 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818459f4

51. Schmelzer, Rodney E. M.D.; Rocca, Gregory J. Della M.D., Ph.D.; Caplin, David A. M.D. Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release: A Review of 753 Cases in 486 Patients, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: January 2006 - Volume 117 - Issue 1 - p 177-185 doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000194910.30455.16

52. Mackinnon, S. E., McCabe, S., Murray, J. F., et al. Internal neurolysis fails to improve the results of primary carpal tun- nel decompression. J. Hand Surg. (Am.) 16: 211, 1991.