Summary Card

Overview

Burn management requires systematic assessment, timely intervention, and specialized care to prevent complications and optimize recovery.

Pathophysiology

Burn injuries trigger a cascade of physiological responses that unfold in a predictable timeline, progressing from acute inflammatory changes to hypermetabolism, multi-organ dysfunction, and long-term systemic effects.

Clinical Assessment

The clinical presentation of a burn is determined by its depth, which affects skin color, blister formation, capillary refill, and sensation.

Initial ABCDE Trauma Assessment

The initial management of burns focuses on early trauma assessment, wound care, supportive measures, and identifying cases requiring surgical intervention or burn center referral.

Surgery

Surgical intervention in burns is essential to remove necrotic tissue, restore skin integrity, and prevent complications such as ischaemia, contractures, and compartment syndrome.

Referral to a Burn Centre

Patients with large burns, specialized area involvement, inhalation injuries, or co-morbid conditions require specialized burn care for better outcomes.

Management of Burn Types

Certain burn types — chemical, electrical, and inhalation burns — have unique pathophysiological effects and require specialized management beyond standard thermal burn care.

Complications

Burn complications can be acute (life-threatening) or chronic (long-term functional and psychological impacts).

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Initial Burn Management

Burn management requires systematic assessment, timely intervention, and specialized care to prevent complications and optimize recovery.

Effective burn care follows a structured approach that includes trauma assessment, wound evaluation, surgical intervention, and long-term rehabilitation. The severity of a burn is determined by depth, total body surface area (TBSA), and associated injuries, guiding treatment decisions.

Initial Assessment & Management

- ABCDE Approach: Airway protection, fluid resuscitation, and hypothermia prevention are priorities in early burn care.

- TBSA & Depth Classification: Burn severity dictates resuscitation needs and determines the necessity for surgical management.

- Early Cooling & Wound Care: Cooling the burn (without ice) within the first 3 hours minimizes tissue damage, while early dressing and tetanus prophylaxis prevent infection.

Specialized Burns & Surgical Considerations

- Chemical, Electrical, & Inhalation Burns: Each requires a tailored approach, including irrigation, cardiac monitoring, or airway protection.

- Surgical Management: Early excision, grafting, and escharotomy prevent infection, restore function, and relieve compartment pressure in severe burn

Pathophysiology of Burns

Burn injuries trigger a cascade of physiological responses that unfold in a predictable timeline, progressing from acute inflammatory changes to hypermetabolism, multi-organ dysfunction, and long-term systemic effects.

Burn injuries trigger complex immune, metabolic, and circulatory responses driven by inflammation and hormonal shifts, causing burn shock, hypermetabolism, and multi-organ dysfunction through immediate, acute, and long-term phases.

Immediate Phase

The first 24 hours after a burn are critical, as they set the stage for fluid shifts, inflammatory activation, and circulatory instability.

Inflammatory Response

This response begins immediately after injury, peaks within the first 24 hours, and can persist for months. Initial cytokine release (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6) increases vessel permeability, reduces T-cell activation, and induces hypermetabolism (Chung, 2024).

- Increased Vascular Permeability: Fluid shifts, oedema, & hypovolaemia.

- Reduced T-cell Activation: Immune suppression

- Hypermetabolic State: Increased energy demands and tissue breakdown.

Burn Shock & Circulatory Changes

Burn shock is due to capillary leak syndrome, resulting in hypovolemia, tissue hypoxia, and cardiac dysfunction.

- Increased Vascular Permeability: Plasma leakage, leading to third spacing

- Loss of Oncotic Pressure: Decreased intravascular volume

- Myocardial Depression: Decreased cardiac output despite normal or increased preload

Fluid resuscitation is essential to restore vascular volume and prevent multi-organ failure.

Acute Phase

This phase is dominated by hypermetabolism and immune suppression, with continued tissue injury progression, and occurs ~24 Hours – 7 days post-burn.

Hypermetabolic Response

The hypermetabolic response peaks around 5–7 days post-burn, following an initial decrease in metabolic rate during the first 48 hours. It plateaus around day 5 and can persist from one to three years in severe cases (Jeshke, 2008).

- Increased Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): 2-3× normal energy expenditure.

- Hyperdynamic Circulation: Increased heart rate, cardiac output, and oxygen consumption.

- Protein Catabolism: Muscle wasting.

- Fat lipolysis and Glycogenolysis: Insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.

Multi-Organ Dysfunction (MODS)

If inflammatory mediators persist, burn patients may develop organ failure (Haruta, 2023).

- Heart: Burn-induced myocardial depression, hypovolemia, and tachycardia.

- Lungs: Acute lung injury & acute respiratory distress syndrome from cytokine-mediated inflammation.

- Renal: Acute kidney injury due to hypoperfusion and myoglobinuria (in electrical burns).

- GI: Ileus and stress ulcers (Curling’s ulcers) due to ischemia and inflammation.

- Immune: Increased susceptibility to sepsis due to T-cell suppression and compromised barrier function.

Aggressive nutritional support with high-protein, high-calorie feeding is critical to prevent muscle wasting and immune dysfunction.

Chronic Phase

Over time, the focus shifts to healing and managing long-term complications, notably chronic hypermetabolism and muscle wasting, which can persist for months to years. More specifically,

- Severe catabolism continues, requiring ongoing rehabilitation and nutrition support.

- Scarring & contractures develop, affecting mobility.

- Persistent insulin resistance increases the risk of diabetes & metabolic dysfunction.

Long-term rehabilitation & physical therapy to restore function and prevent complications.

Clinical Assessment of Burns

The clinical presentation of a burn is determined by its depth, which affects skin color, blister formation, capillary refill, and sensation.

History

A structured history is essential for evaluating burn severity, systemic impact, and complications. The following five key questions help guide assessment.

- Time of Burn

Time elapsed since injury influences treatment urgency—delayed presentation increases the risk of infection and complications.

- Duration of Exposure

Longer exposure = deeper burns, particularly for flame, electrical, and chemical burns.

- First Aid & Initial Management at Scene

Running cool water (not ice) within 20 minutes of injury reduces burn severity. If transferred from another hospital, clearly note when fluid resuscitation started.

- Type of Burn

Different burn types have unique characteristics that influence depth and complications. For example,

- Scald Burns: Temperature, viscosity (e.g., milk retains heat longer), and solutes (e.g., sugar/salt raise boiling point).

- Flame Burns: Longer exposure & enclosed spaces (inhalation injury risk).

- Chemical Burns: Acids cause coagulative necrosis (protective eschar limits penetration); alkalis cause deeper liquefactive necrosis.

- Electrical Burns: Voltage (high-voltage penetrates deeper, risk of arrhythmias), contact duration (increases muscle necrosis).

- Contact Burns: Prolonged contact typically leads to full-thickness burns.

- Additional Medical Considerations

Other important factors, as per the AMPLE approach, include (Schafer, 2023),

- Allergies: Identify reactions to medications or dressings.

- Medications: Consider drugs that impair healing (e.g., steroids, anticoagulants, immunosuppressants).

- Past Medical history: Diabetes, vascular disease, or immunosuppression delay healing.

- Last Oral Intake: Relevant for fluid resuscitation and surgical planning.

- Events: As discussed above.

Voice changes may indicate inhalation injury, confusion suggests secondary trauma, and delayed presentation raises suspicion of non-accidental injury.

Examination

A thorough clinical examination focuses on burn depth, total body surface area (TBSA) estimation, and associated injuries to guide management.

Burn Depth Assessment

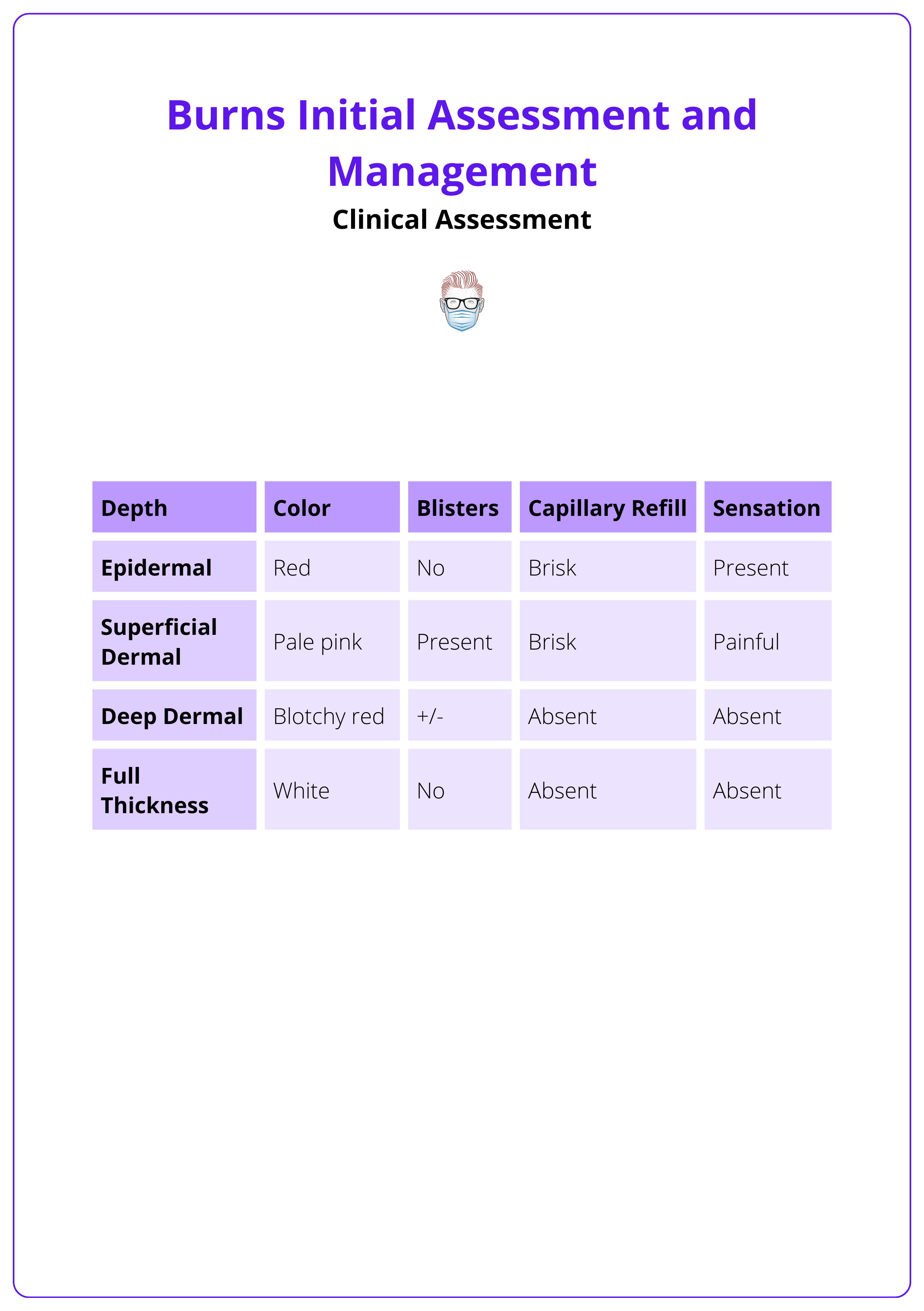

Burns are classified based on appearance, sensation, and capillary refill.

- Superficial: Red, painful, blanches, no blisters.

- Superficial Partial-Thickness: Pink, moist, blisters, brisk capillary refill.

- Deep Partial-Thickness: Pale, sluggish refill, reduced sensation.

- Full-Thickness: White/leathery, no pain, no capillary refill.

The table below highlights key burn depth characteristics (RCHM, 2020). For detailed guidance, refer to our article on Burn Depth Assessment.

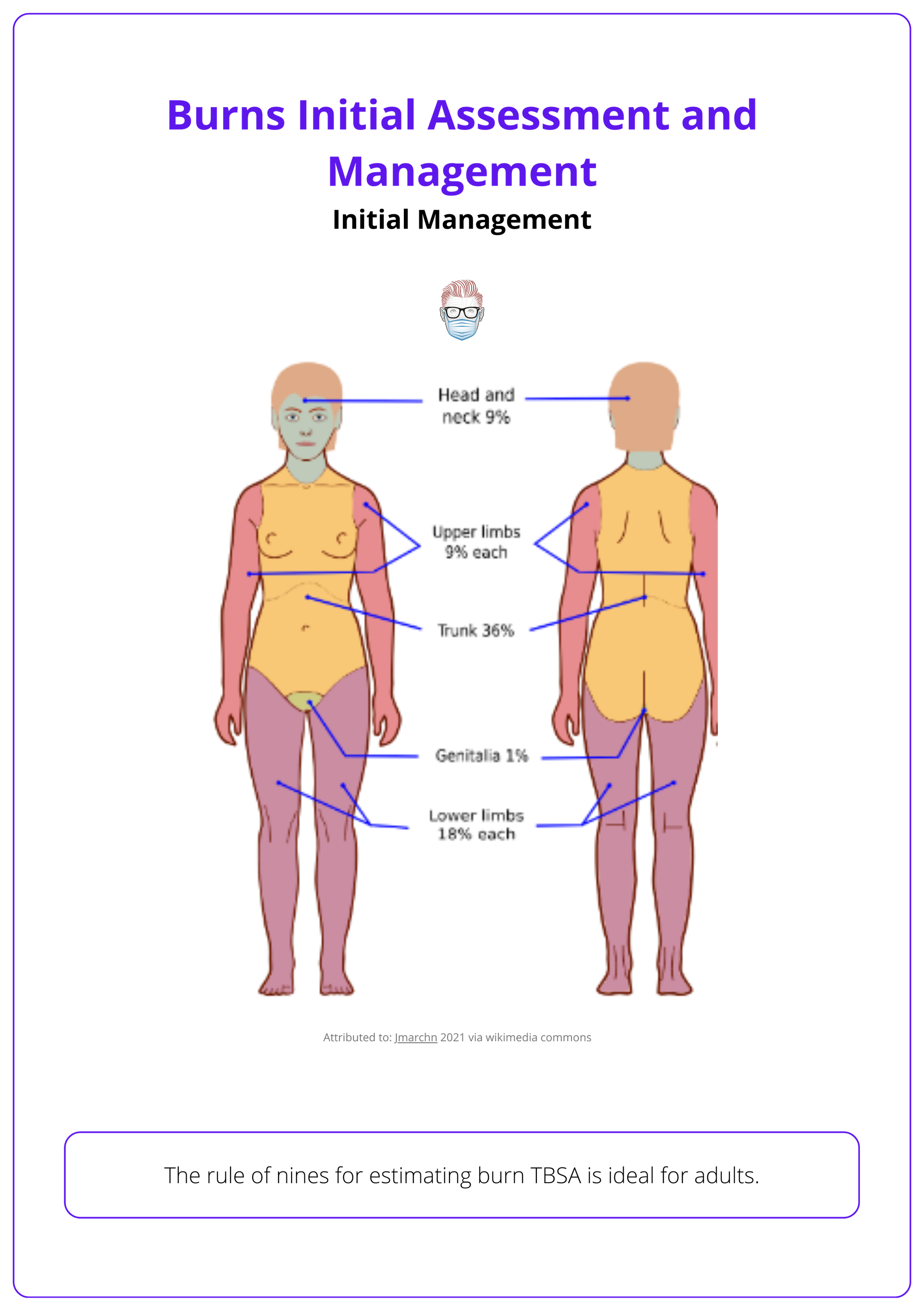

TBSA Estimation

Accurate TBSA calculation determines fluid resuscitation needs.

- Rule of Nines – Quick adult estimation.

- Lund & Browder Chart – More precise, especially for children.

- Palm Method – Patient’s palm = ~1% TBSA, useful for small burns.

For comprehensive guidance on calculating Total Body Surface Area (TBSA), see our detailed article on TBSA Calculation.

Associated Injuries

- Smoke Inhalation: Signs include singed nasal hair, soot around the mouth, voice changes, or respiratory distress, indicating high risk of airway injury.

- Associated Trauma: Look for blunt or blast injuries, such as fractures, traumatic brain injury, or internal bleeding, common in explosions, falls, or motor vehicle accidents.

- Non-Accidental Injury (NAI): Suspect abuse with glove-and-stocking burn patterns (clear immersion lines), delayed presentation, or inconsistent injury history.

Patients’ smoking habits should be documented, as they may affect blood gas analysis and increase the risk of inhalation injury (Hettiaratchy, 2004).

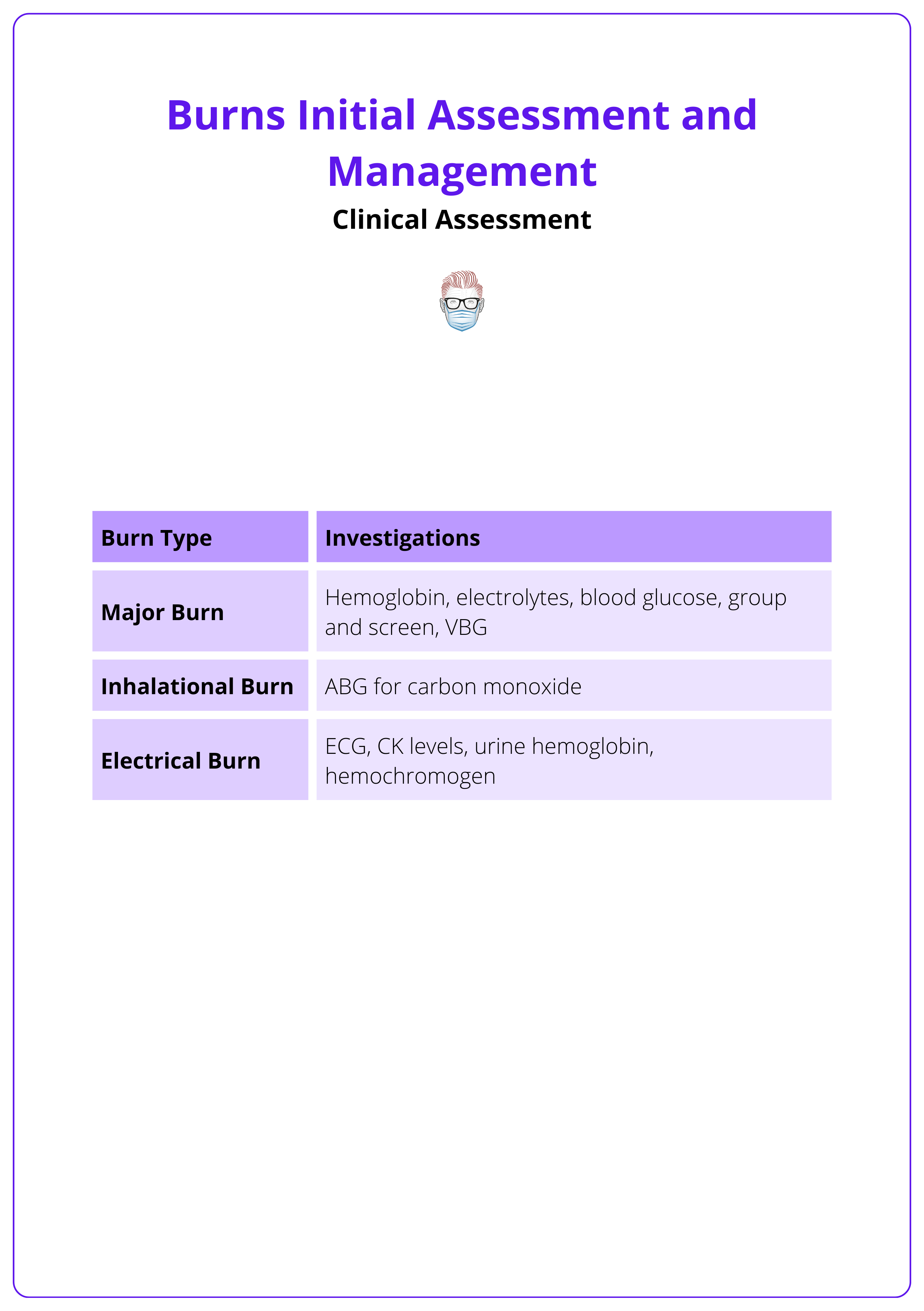

Investigations

Investigations are guided by burn type, severity, and systemic involvement, helping to detect shock, inhalation injury, organ dysfunction, or associated trauma.

Routine Blood Tests

- Full Blood Count: Monitors hemoconcentration (early) and infection risk (later).

- Urea & Electrolytes (U&Es): Assesses fluid balance, renal function, and electrolyte disturbances.

- Coagulation Screen & Lactate: Important in severe burns and shock states.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) & Carboxyhemoglobin: Essential for inhalation injury, carbon monoxide poisoning, and metabolic acidosis.

Specialised Tests

- Inhalation Injury: Carboxyhemoglobin, ABG, Chest X-ray (CXR).

- Electrical Burns: ECG, Creatine Kinase (CK), Myoglobin (rhabdomyolysis risk).

- Chemical Burns: Serum pH, toxin screening for systemic absorption.

Imaging

Additional imaging is required if associated injuries are suspected.

- Chest X-Ray (CXR): If inhalation injury or blast trauma is suspected.

- Pelvic X-Ray: For falls, blast injuries, or suspected fractures.

These investigations for burns patients are summarised below.

Initial ABCDE Trauma Assessment for Burns

The initial management of burns focuses on early trauma assessment, wound care, supportive measures, and identifying cases requiring surgical intervention or burn center referral.

Burn patients should be assessed systematically using the ABCDE framework, as many have airway compromise, inhalation injuries, or associated trauma.

A. Airway

Early airway management is critical as inhalation injuries can cause rapid airway swelling.

- Assess for voice changes, soot in the mouth, or singed nasal hair, which suggest inhalation injury.

- Secure the airway early with endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy if needed.

B. Breathing

Circumferential burns of the chest and inhalation injuries can cause respiratory distress.

- Assess breath sounds, respiratory rate, and effort to detect restrictive burns or inhalation injury.

- Administer 100% oxygen if carbon monoxide poisoning is suspected (carboxyhemoglobin >10%).

C. Circulation

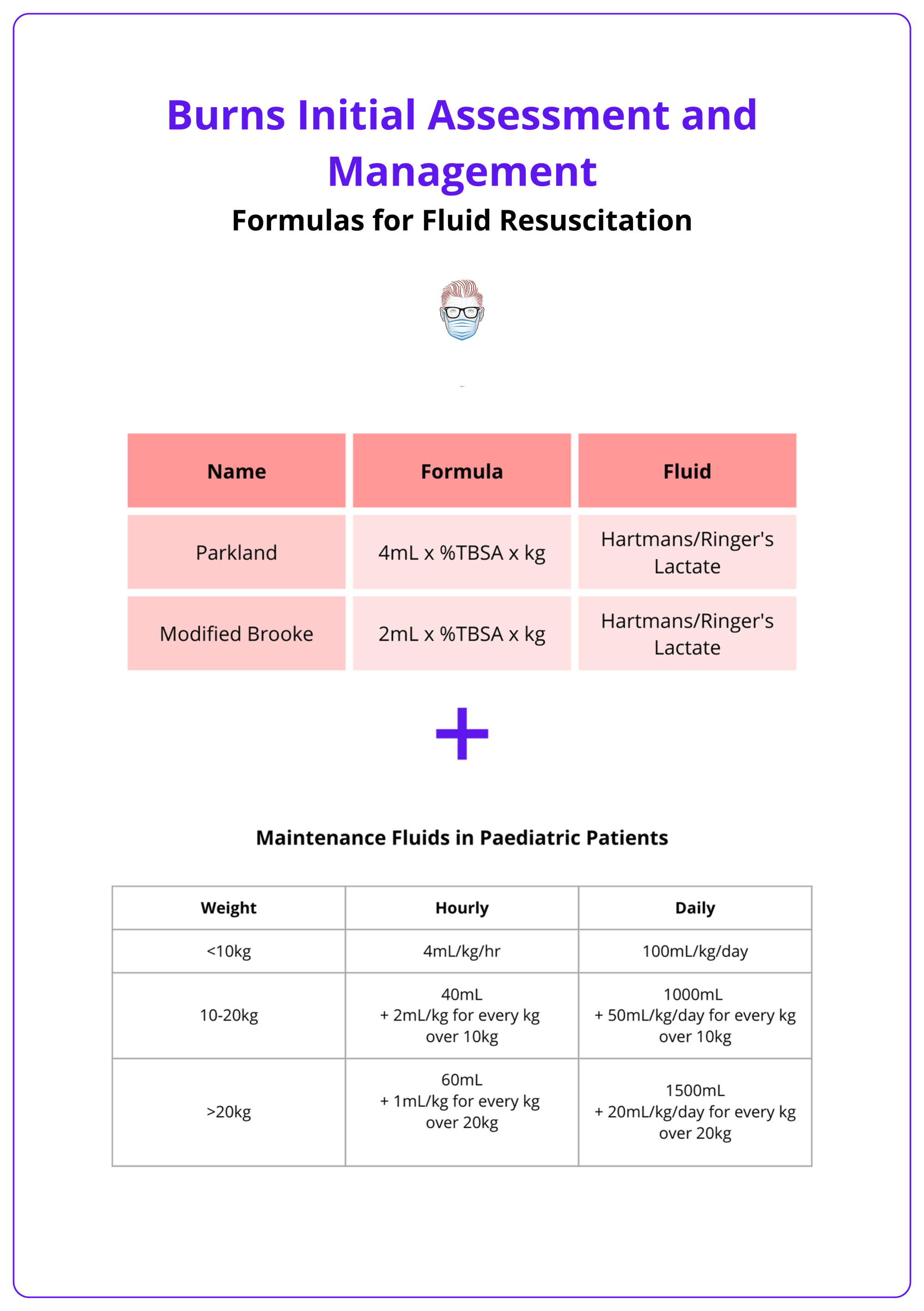

Burns cause fluid loss and systemic shock, requiring early IV fluid resuscitation.

- Check Peripheral Circulation: Deep/full-thickness circumferential extremity burns can act as tourniquets, worsening edema and impairing perfusion (Hettiaratchy, 2004).

- Establish Two Large-Bore IV Lines Start goal-directed resuscitation (Parkland Formula: 2–4 mL/kg/%TBSA in 24 hrs—half within first 8 hrs, remainder over next 16 hrs); use warmed IV fluids and maintain a warm environment.

- Monitor Urine Output via urinary catheter: Target: adults 0.5–1 mL/kg/hr, children 1–2 mL/kg/hr, electrical burns 1.5–2 mL/kg/hr; adjust fluids by ±10–20% to maintain targets (RCHM, 2020). (RCHM, 2020).

The image below breaks down the Parkland and modified Brooke formula for burns.

D. Disability

Assess neurological status promptly to identify potential secondary complications or underlying conditions:

- Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS): Low scores may indicate traumatic brain injury (TBI), hypoxia, intoxication, or pre-existing neurological conditions.

- Early Shock Considerations: Severe hypovolemia is unusual immediately after burns; consider alternative causes such as hemorrhage or cardiogenic dysfunction (Hettiaratchy, 2004).

Burn patients normally exhibit a hyperadrenergic state (HR 100–120 bpm); higher rates suggest hypovolemia, inadequate analgesia, or additional trauma (ISBI 2016).

E. Exposure & Hypothermia Prevention

Fully expose and carefully log-roll the patient to inspect all injuries thoroughly. After examination, prevent hypothermia by promptly,

- Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) Estimation: Expose the whole body and log-roll the patient to assess the posterior surfaces. Superficial burns should not be included in the TBSA calculation.

- Cooling Burns: Running cool water (20 minutes, ideally within 3 hours post-burn - RCHM, 2020), removing wet clothing and dressings immediately afterward.

- Initial Wound Care: Cleaning, removal of nonviable tissue, and appropriate dressings to optimize healing.Remove loose, necrotic skin through mechanical debridement (tangential excision), gentle scrubbing, or intraoperative irrigation

- Dressings: For superficial partial-thickness burns, occlusive dressings are preferred to maintain moisture. For deeper burns, closed dressings are standard; if early excision is delayed, use open dressings, or moist dressings if heat-preserving options are unavailable (ISBI, 2016).

Additional Early Treatments

- Feeding: Start early enteral feeding promptly (oral or nasogastric) to reduce ulcers and muscle loss; nasogastric feeding is preferred if gastrointestinal function is intact (Schafer, 2023).

- Tetanus Prophylaxis: Burn wounds are tetanus-prone. If vaccination status is uncertain or incomplete, administer Tetanus toxoid if the patient is inadequately vaccinated.Tetanus immunoglobulin in non-immunized individuals (ISBI 2016).

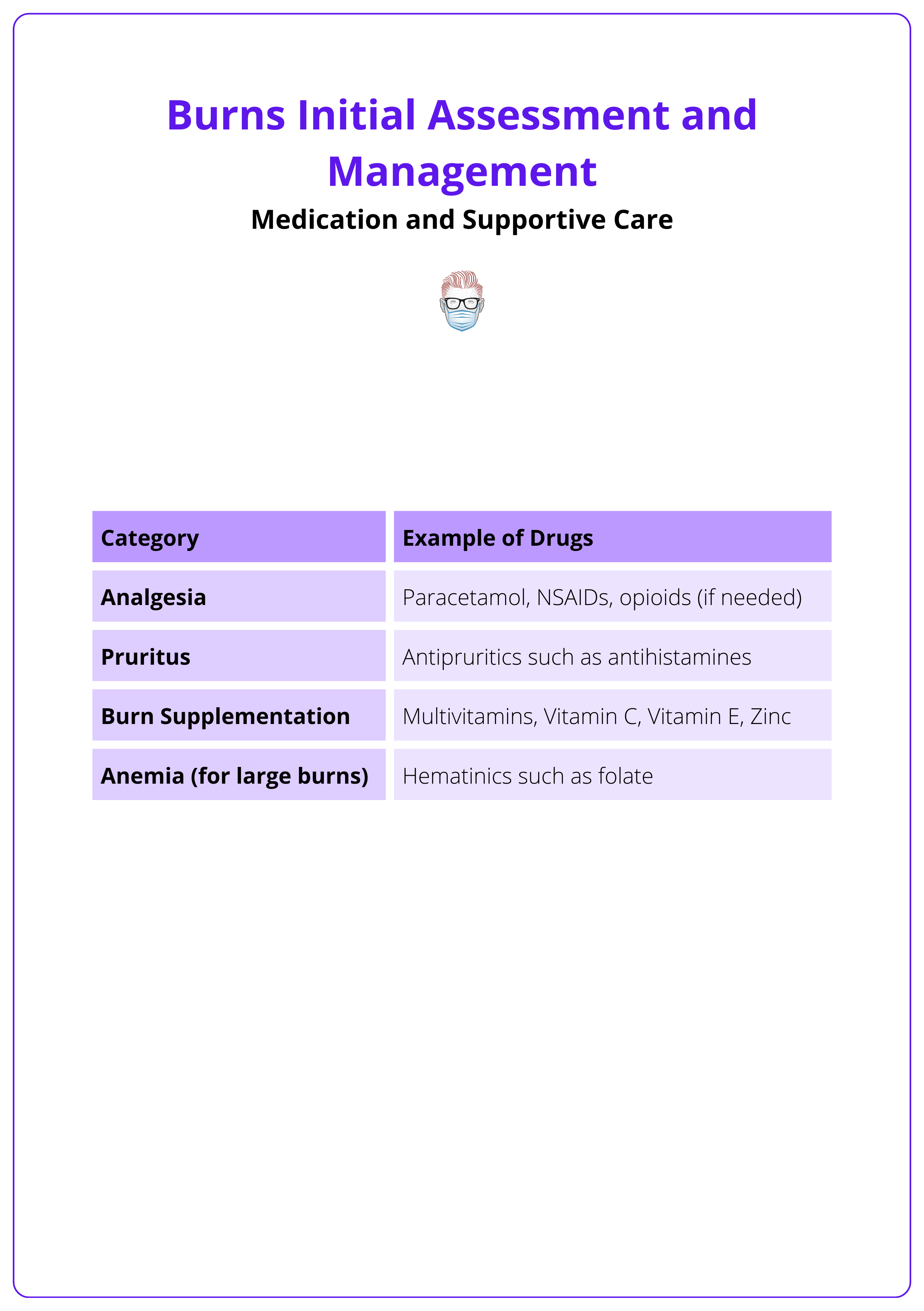

- Medication: Medication to address analgesia, pruritus, and burn supplementation should be prescribed for burn patients. See the table below for examples of drugs.

Surgery for Burns Management

Surgical intervention in burns is essential to remove necrotic tissue, restore skin integrity, and prevent complications such as ischaemia, contractures, and compartment syndrome.

The need for burn surgery is guided by extent, depth, location of burns, and patient condition. The goal is to remove non-viable tissue, promote healing, and prevent complications. The approach includes early excision, grafting, and escharotomy when indicated.

Timing of Excision

Surgical excision of necrotic tissue is performed based on patient status and wound progression.

- Early Excision (≤10 days): The standard of care when feasible, removing eschar before infection or spontaneous sloughing (ISBI, 2016).

- Delayed Excision (10–21 days): Used when partial spontaneous healing is expected, with eventual removal of necrotic tissue.

- Late Grafting: Performed after granulation tissue formation, requiring debridement of slough before coverage.

- Staged Burn Excision: Manage option for extensive injuries in multiple sessions.

Depth of Excision

Excision strategies vary depending on burn severity and location.

- Tangential Excision: Sequential removal of necrotic layers, preserving viable tissue; ideal for high-voltage electrical burns or deep burns.

- Fascial Excision: Full-thickness removal down to deep fascia, used for extensive burns requiring rapid debridement.

Grafting Techniques

Following excision, wound coverage is essential to restore function and prevent excessive scarring.

- Early Autografting: Preferred whenever possible for faster wound closure and lower infection risk.

- Skin Substitutes: Used when autografts are unavailable, providing temporary or permanent coverage.

Hemostasis during burn excision involves epinephrine infiltration, tourniquets, electrocautery, topical agents, hypothermia prevention, compression dressings, and staged procedures.

Escharotomy

Escharotomy involves making incisions from healthy skin to healthy skin (or joint-to-joint, if needed) to fully relieve constriction without damaging deeper structures (ISBI, 2016). It's indicated in,

- Limb Ischemia: Circumferential burns constricting circulation and causing impaired perfusion.

- Chest Burns: Restrictive burns limit chest expansion, causing respiratory distress.

- Abdominal Compartment Syndrome: Elevated intra-abdominal pressure compromising organ function.

Fasciotomy

Compartment syndrome, more common in electrical burns, occurs when increased pressure within muscle compartments leads to ischemia and necrosis. Key principles include,

- Fasciotomy is required for pressure relief and tissue perfusion.

- Monitor for rhabdomyolysis (myoglobinuria) and prevent acute kidney injury with aggressive IV fluids.

Referral to a Burn Centre

Patients with large burns, specialized area involvement, inhalation injuries, or co-morbid conditions require specialized burn care for better outcomes

Burn center referral criteria vary internationally, but generally include the following.

- Extent & Depth: Partial-thickness burns >10% TBSA, full-thickness burns, or circumferential burns.

- Specialized Areas: Burns involving the face, eyes, neck, hands, feet, joints, genitalia, or perineum.

- High-Risk Burns: Chemical, electrical, lightning strike, and inhalation injuries.

- Vulnerable Populations: Infants (<1 year), elderly (>50 years), or patients with co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease).

- Associated Trauma: Burns with fractures, spinal cord injuries, or multi-system trauma.

Management of Burn Types

Certain burn types — chemical, electrical, and inhalation burns — have unique pathophysiological effects and require specialized management beyond standard thermal burn care.

Chemical Burns

Chemical burn vary in severity based on the type of chemical and duration of exposure. Alkali burns cause liquefactive necrosis, allowing deep penetration, while acid burns cause coagulative necrosis, forming a protective eschar that limits tissue damage Schafer, 2023).

Immediate Management

- Decontamination: Remove the chemical promptly to prevent further penetration.

- PPE Use: Prevent secondary contamination by wearing gloves and protective equipment.

- Clothing & Residue Removal: Brush off dry powders before irrigation (Haruta, 2023)

- Irrigation: Flush with warm water for 20–30 minutes (extend to 60 minutes for alkali burns), ensuring proper drainage to avoid further exposure

Special Considerations include,

- Hydrofluoric Acid Burns: Cause hypocalcemia, treated with topical and IV calcium gluconate; severe cases may require emergent excision for refractory hypocalcemia.

- Tar Burns: Cool to solidify tar and dissipate heat, then remove with a solvent (e.g., Neosporin ointment) to dissolve it and minimize skin trauma (Haruta, 2023).

Electrical Burns

Electrical burns cause deep tissue damage despite minimal surface injury. High-voltage (>1000V) burns can lead to severe internal injuries, including cardiac arrhythmias, muscle necrosis, and compartment syndrome.

Immediate Management

Patients require systemic monitoring, fluid resuscitation, and evaluation for deep tissue injury.

- Assess for associated trauma (falls, fractures, spinal injuries).

- Monitor for dysrhythmias — perform ECG and 24-hour cardiac monitoring if needed.

- Monitor for rhabdomyolysis — check CK, urine myoglobin, and hemoglobin.

- Aggressive fluid resuscitation with target urine output of 1.5–2 mL/kg/hr.

- Alkalinize urine with sodium bicarbonate to prevent renal injury from myoglobinuria.

Surgical Considerations

Early fasciotomy is required if compartment syndrome is diagnosed, and urgent debridement may be necessary for severe high-voltage injuries to improve limb salvage.

Inspect oral commissures for electrical cord burns. Watch for labial artery bleeding (7–10 days post-burn), managed with direct pressure inside the cheek (Haruta, 2023).

Inhalation Burns

Inhalation injuries occur due to smoke, heat, and toxic gas exposure and can affect the upper airway, lower respiratory tract, or cause systemic poisoning (CO or cyanide toxicity). Early recognition is critical for preventing airway obstruction and respiratory failure.

- Singed facial hair, soot in or around the mouth, carbonaceous sputum.

- Hoarseness, stridor, increased work of breathing.

- Inability to tolerate secretions and signs of upper airway edema.

Treatment depends on the severity of the injury and risk of airway obstruction.

- Observe and monitor closely for delayed airway edema.

- Elevate the head of the bed to reduce swelling and support breathing.

- Secure the airway early if airway compromise is suspected (jaw-thrust, intubation, or surgical airway if needed).

- For CO poisoning, administer 100% high-flow oxygen for at least 6 hours (ISBI, 2016).

- Lung-protective ventilation strategies should be used in patients requiring mechanical ventilation.

A normal oxygen saturation or clear chest X-ray does not exclude inhalation injury — clinical suspicion is key.

Complications of Burns

Burn complications can be acute (life-threatening) or chronic (long-term functional and psychological impacts).

Acute Complications

Immediate risks include breathing disturbances, infection, and hypovolemia, while long-term effects involve scarring, hypermetabolism, and psychological distress.

Systemic Instability

Severe burns disrupt fluid balance, thermoregulation, and immune response, leading to multi-organ dysfunction if not managed promptly.

- Breathing Problems: Inhalation injuries can cause airway swelling, carbon monoxide poisoning, or lung injury from toxic fumes.

- Hypovolemia and Shock: Severe burns result in fluid loss and circulatory collapse if resuscitation is inadequate.

- Hypothermia: Skin loss impairs temperature regulation, worsening metabolic stress.

Infection and Wound-Related Risks

Burn wounds create an ideal environment for bacterial invasion, making infection a leading cause of sepsis and delayed healing.

- Sepsis Risk: Major burns compromise the immune barrier, increasing the likelihood of systemic infection.

- Tetanus: Burn wounds are particularly susceptible to tetanus, requiring vaccination if the status is uncertain.

Blood and Muscular Complications

- Anemia: Burns exceeding 10% TBSA (full-thickness) often lead to significant red blood cell loss.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Prolonged immobilization increases clotting risks, predisposing patients to DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE).

- Electrical Burns: High-voltage injuries can cause compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, and cardiac arrhythmias, requiring close monitoring.

Chronic Complications

Metabolic and Musculoskeletal Effects

Large burns trigger a prolonged hypermetabolic state, leading to muscle loss, bone density reduction, and growth impairment in children.

- Hypermetabolism: Increases nutritional demands, requiring long-term dietary management.

- Bone and Muscle Wasting: Persistent catabolism reduces muscle mass and weakens bones, increasing the risk of fractures.

Scarring and Functional Impairment

Burn scars can significantly affect movement and quality of life, particularly in joint or facial burns.

- Keloids and Contractures: Thick, raised scars can restrict mobility, especially if burns involve joints, hands, or the face.

- Chronic Pain: Some patients experience neuropathic pain or hypersensitivity in healed burn areas.

Psychosocial and Economic Impact

Burn injuries often lead to emotional trauma and social difficulties, especially in cases of visible scarring.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Anxiety, depression, and flashbacks are common in burn survivors.

- Body Image Concerns: Visible scarring can result in low self-esteem and social withdrawal.

- Economic and Social Hardship: In low-resource settings, severe burns may lead to poverty, social exclusion, or child abandonment due to disability.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Burn management depends on type, depth, extent, location, and patient factors like age and comorbidities.

2. Pathophysiology: Burns trigger hypermetabolism, inflammation, hormonal shifts, and organ dysfunction, with Jackson’s Zones defining tissue damage.

3. Clinical Assessment: Burn depth determines skin appearance, blistering, capillary refill, and sensation, while AMPLE history aids evaluation.

4. Initial Management: Cool burns (20 min, running water), prevent hypothermia, follow ABCDE approach, ensure fluid resuscitation, and perform escharotomies if needed.

5. Wound Care: Debride necrotic tissue, apply occlusive dressings for superficial burns, and consider early excision and grafting for deeper burns.

6. Medications & Supportive Care: Manage pain with multimodal analgesia, treat pruritus with antihistamines, and start early enteral feeding. Burn center referral is required for burns >10% TBSA, full-thickness burns, inhalation injuries, and burns in critical areas.

7. Managing Special Burn Types: Chemical burns require immediate irrigation, electrical burns risk cardiac arrhythmias, inhalation burns need 100% O₂, and minor burns require basic wound care.

8. Complications: Acute risks include airway obstruction, sepsis, and hypothermia, while chronic issues involve scarring, PTSD, and long-term hypermetabolism.

Further Reading

- Hettiaratchy S, Papini R. Initial management of a major burn: I--overview. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1555-7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1555. PMID: 15217876; PMCID: PMC437156.

- Schaefer TJ, Szymanski KD. Burn Evaluation and Management. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430741/

- Schaefer TJ, Nunez Lopez O. Burn Resuscitation and Management. [Updated 2023 Jan 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430795/

- Haruta A, Mandell SP. Assessment and Management of Acute Burn Injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2023 Nov;34(4):701-716. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2023.06.019. Epub 2023 Jul 27. PMID: 37806692.

- ISBI Practice Guidelines Committee; Steering Subcommittee; Advisory Subcommittee. ISBI Practice Guidelines for Burn Care. Burns. 2016 Aug;42(5):953-1021. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.05.013. PMID: 27542292.

- Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, Kulp G, Suman OE, Norbury WB, Branski LK, Gauglitz GG, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2008 Sep;248(3):387-401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. PMID: 18791359; PMCID: PMC3905467.

- The Royal Children’s Hopsital Melbourne Acute burns June 2020 https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/burns/ Accessed on 5th March 2025

- Chung 2024 Grabb and Smith's Plastic Surgery: 9th Edition September 2024 page 147-148