Summary Card

Definition

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS) is a peripheral neuropathy that involves disruption of the anterior interosseous nerve.

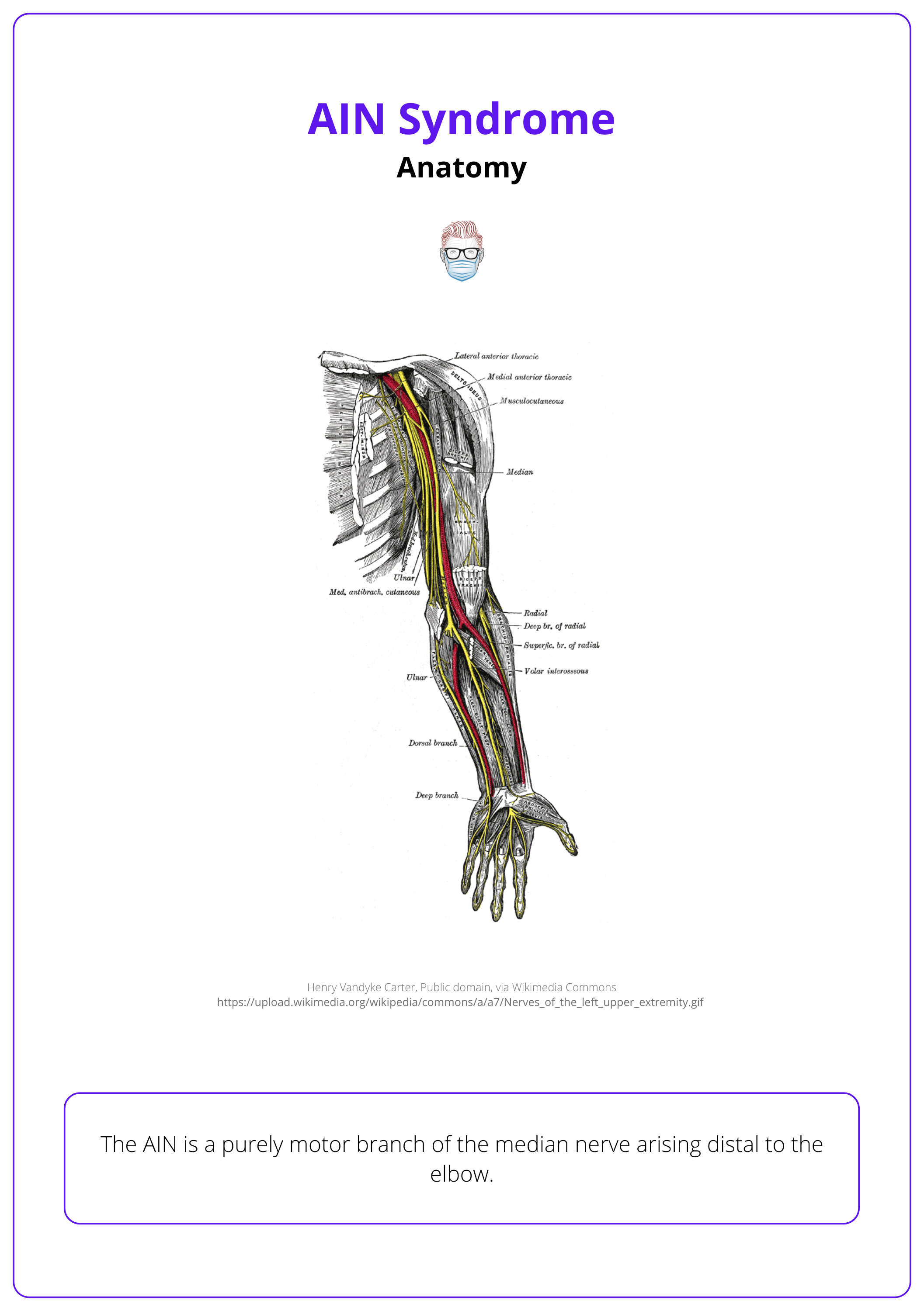

Anatomy

The AIN is purely a motor branch of the median nerve arising distal to the elbow.

Aetiology

Initially thought to be caused by compression and entrapment, the currently proposed pathophysiology includes immune neuropathy.

Presentation

AIN syndrome presents as an isolated paralysis of the AIN-supplied muscles (FPL, FDP, and PQ) and no sensory loss.

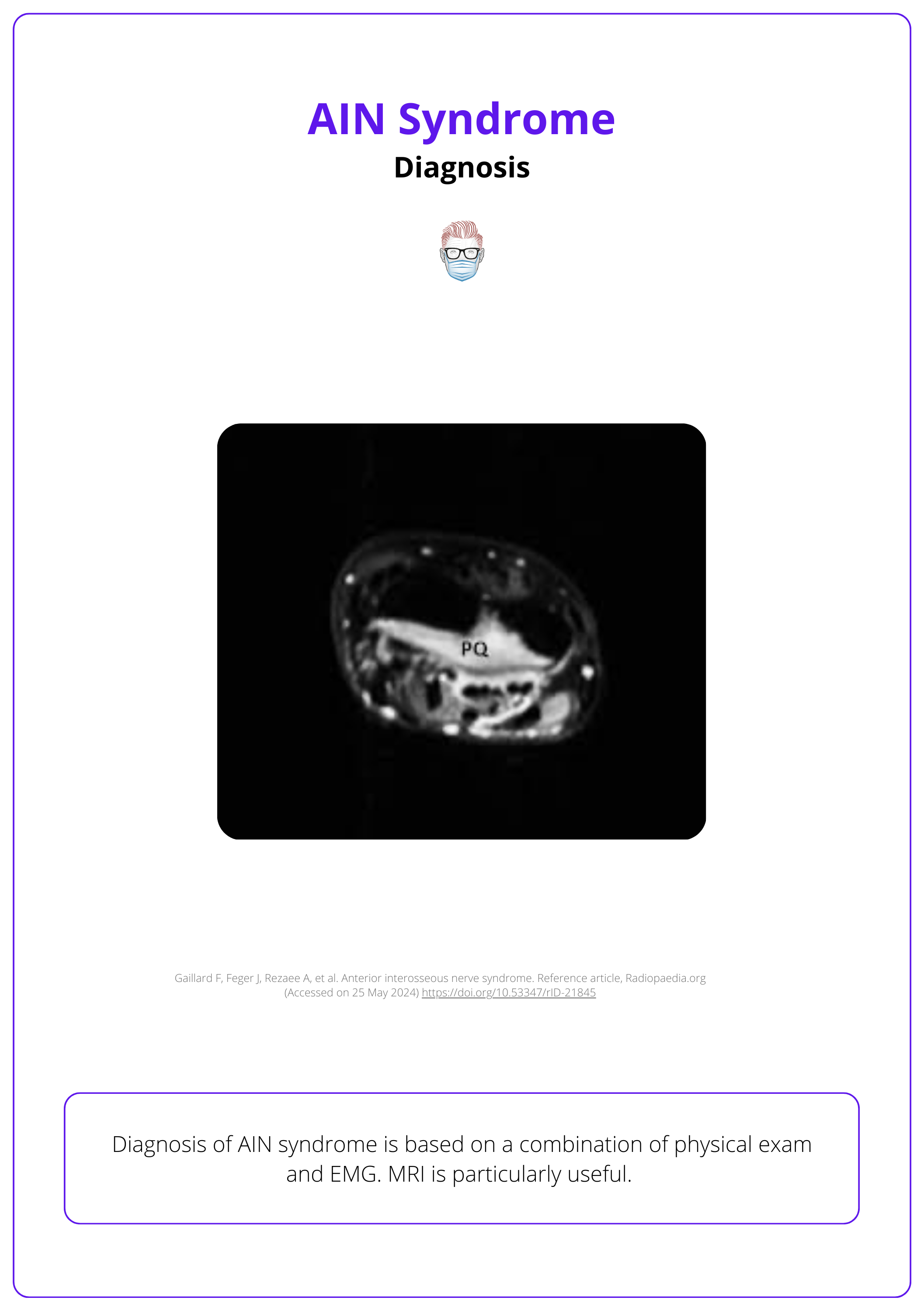

Investigations

Diagnosis is based on a combination of physical exam and EMG. MRI and US can also be useful.

Differential Diagnoses

Flexor tendon rupture, proximal nerve compression, and other compressive neuropathies such as pronator syndrome or carpal tunnel syndrome.

Treatment

Initially, a non-operative approach is recommended, followed by surgical decompression if symptoms persist.

Complications

Persistent AIN motor deficit can be treated by tendon or nerve transfer.

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow.

Reviewer: Dr Suzanne Thomson, Educational Fellow.

Definition of AIN syndrome

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS) is a peripheral neuropathy that involves disruption of the anterior interosseous nerve.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS) is a rare form of peripheral neuropathy that involves an isolated palsy of the anterior interosseous nerve – a branch of the median nerve (Li, 2022).

It is also known as Kiloh-Nevin's syndrome. It refers to the constellation of signs and symptoms referable to the weakness of:

- pronator quadratus,

- flexor pollicis longus, and

- flexor digitorum profundus to the index finger (Chin, 2001).

This condition can present in a complete or incomplete form: (Hill, 1985)

- Complete AINS: All three muscles are affected, leading to notable functional impairments such as difficulty in pinching and gripping.

- Incomplete AINS: Only one or two of the innervated muscles show symptoms, which may result in less apparent clinical signs.

Recently selective compression of the AIN fascicles within the median nerve above the forearm has also been described as giving rise to this group of symptoms (Krishnan, 2020).

AINS is quite rare, comprising <1% of all upper limb nerve syndromes, affecting men and women, as well as dominant and nondominant upper extremities equally (Li, 2022).

Anatomy of AIN Syndrome

The AIN is a purely motor branch of the median nerve arising ~4cm distal to the medial epicondyle. There is no sensory component.

AIN is a terminal motor branch of the median nerve. It has the following characteristics:

- Arises from the median nerve approximately 4cm distal to the medial epicondyle (and 5-8 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle).

- Travels between FDS and FDP.

- Continues between FPL and FDP.

- Lies on the anterior surface of the interosseous membrane travelling with the anterior interosseous artery to the pronator quadratus.

The image below illustrates the anatomy of AIN syndrome.

It innervates 3 muscles in the forearm.

- Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP): Affects the index and middle fingers, facilitating flexion at the distal interphalangeal joints.

- Flexor Pollicis Longus (FPL): Enables flexion at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb.

- Pronator Quadratus (PQ): Responsible for pronation of the forearm, allowing the palm to face downwards.

The AIN has no cutaneous sensory component.

Terminal branches innervate the joint capsule and the intercarpal, radiocarpal, and distal radioulnar joints and can lead to wrist pain as a part of AIN syndrome presentations.

Aetiology of AIN Syndrome

Initially thought to be caused by compression and entrapment, the currently proposed pathophysiology includes immune neuropathy.

Pathophysiology

Originally, compression and entrapment of the AIN were suspected to be the etiology of AINS. However, the pathophysiology of AINS is now widely debated and remains unclear. Current theories include: (Li, 2022; Boeckstyns, 2022, Krishnan, 2020)

- Idiopathic immune-mediated neuritis.

- Intrinsic compression in the forearm or selective fascicular compression of the AIN fascicles above the forearm prior to branching.

More recent evidence suggests that AINS may be a variation of neuralgic amyotrophy (NA), which is an idiopathic immune neuropathy (Li, 2022)

Compression

The AIN can be internally entrapped/compressed by muscles, tendons, blood vessels, and bones. More specifically:

Muscles of the forearm:

- Pronator teres heads muscle (The most common site of entrapment).

- The proximal edge of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) arch.

- Palmaris longus.

- An accessory head of the FPL (Gantzer’s muscle) (Degreef, 2004).

Other sites of compression include:

- Bicipital aponeurosis and Tendinous bands.

- Thrombosed radial or ulnar artery branch in the mid-forearm.

- Osseous spurs.

External compressive aetiology (e.g. supracondylar fracture) is not considered true AINS. Symptoms have consistently been shown to resolve once the external compression is eliminated.

Direct traumatic injury to the AIN, either due to upper extremity trauma or extrinsic mass (i.e. tumour) is rare and not considered true AINS due to differing pathophysiology (Li, 2022).

Presentation of AIN Syndrome

AIN syndrome presents as an isolated paralysis of the AIN-supplied muscles (FPL, FDP, and PQ) and no sensory loss. Wrist pain may be evident.

Patients affected typically present in their 40s. A positive prognostic variable is a patient less than 40 as they are expected to have faster recovery. This may be after a trauma or spontaneous (Sood, 1997).

Pain

- If present, there is prodrome pain that is transient and hours to 2-3 weeks.

- It is usually acute, poorly localised in the proximal volar forearm and the cubital fossa, and worsened by repetitive action.

Motor Weakness

- FPL: loss of thumb IPJ flexion.

- FDP Index: loss of DIPJ flexion.

- PQ: reduced forearm pronation.

- OK Sign: struggle to bring the tips of the thumb and index finger together.

- Key Pinch: unable to resist a paper pinch between the thumb and index finger or compensates by extending the thumb and index finger joints.

Provocative Tests

- Pronator quadratus weakness presents as weak resisted pronation with the elbow fully flexed.

- To distinguish from FPL attritional rupture (common in rheumatoid arthritis), passively flex and extend the wrist to check for the tenodesis effect in an intact tendon.

The Martin-Gruber communicating branch, a unique connection between the median or AIN and ulnar nerves, may contribute to intrinsic muscle weakness in addition to the characteristic palsy triad of AINS (Li, 2022).

Investigations of AIN Syndrome

Diagnosis is based on a combination of physical exam and EMG. MRI is increasingly useful.

Neurophysiology Investigations

This investigation can diagnose and assess the severity of AIN palsy, rule out more proximal lesions, and evaluate nerve recovery. Additionally, EMG helps differentiate idiopathic AIN syndrome (a part of neuralgic amyotrophy) from compression neuropathy. Findings include:

- Abnormal activity and prolonged latency in the FPL, FDP, and PQ (Li, 2022).

- It may also show fibrillations and sharp waves in the affected muscles.

- Sensory nerve conduction studies of the median nerve should be normal, as the anterior interosseous nerve lacks sensory innervation (Akhondi, 2023).

Sensory nerve conduction studies of the median nerve should be normal as there is no sensory innervation to the anterior interosseous nerve.

MRI

T2-weighted fat-saturated images show increased signal intensity within the muscles innervated by the AIN (FPL, FDP, and PQ). An MRI "bullseye" sign may be seen in the nerve proximal to the point of compression (Park, 2024).

The image below illustrates the MRI presentation of AIN syndrome.

Ultrasound

The US can demonstrate anatomical causes of compression and the severity of compression (derived from calculating a ratio of nerve diameter proximal and distal to the lesion) (Park, 2024).

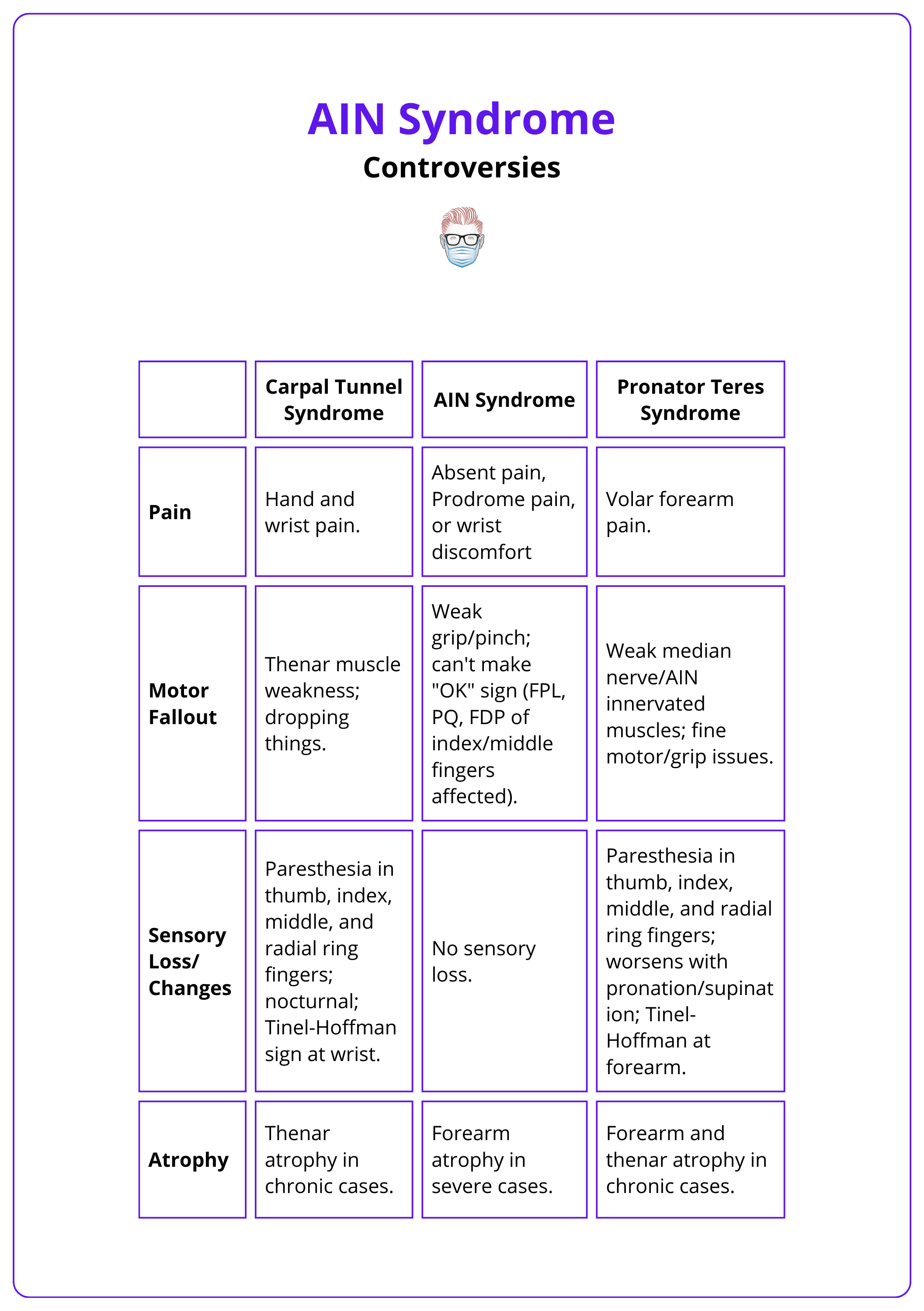

Differential Diagnoses of AIN Syndrome

Flexor tendon rupture, proximal nerve compression, and other compressive neuropathies such as pronator syndrome or carpal tunnel can all present similarly.

It is important to be able to differentiate between AIN Syndrome, Pronator Syndrome, and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Other differentials include an FDP index rupture, FPL rupture, or brachial neuritis.

The differences in compressive neuropathies are detailed in the table below.

To exclude FPL tendon rupture, the wrist is flexed passively and extended to confirm that the individual has an intact tenodesis effect.

Treatment of AIN Syndrome

The non-operative approach initially, along with subsequent surgical decompression if symptoms persist.

Due to the self-limiting nature of AINS, conservative and symptomatic management is the first line of treatment in the absence of a demonstrable acute external compressive cause. It includes: (Li, 2022)

- Multimodal Analgesia.

- Hand Therapy: contracture prevention, splinting of the elbow near 90 degrees of flexion (or position of most comfort for the patient).

- Other considerations: Electrical stimulation therapy, Supplemental vitamin B12.

Recovery generally begins 3 to 12 months after onset of symptoms with full resolution taking up to 18 months.

Surgical intervention

Indications (Chin, 2001; Aljwader, 2016)

- No improvement is noted within 6 to 12 months.

- If the neurologic condition worsens, surgical exploration may be warranted.

- Confirmed compression neuropathy.

Surgical treatment consists of:

- Exploration

- Neurolysis

- Decompression - including endoscopic decompression

Endoscopic decompression can be performed, with advantages considered to be smaller scars, less blood loss, and improved recovery time. However, it is not suitable for all cases and has a learning curve.

Complications of AIN Syndrome

Persistent AIN motor deficit can be treated by tendon transfer.

Persistent AIN motor deficit may occur after conservative treatment or surgical decompression and can be treated by tendon transfer.

- Brachioradialis to FPL transfer.

- FDP of 3rd and 4th finger to the index finger.

Tendon transfer would usually only be considered > 1 year after onset of symptoms.

For all tendon transfers, equivalent nerve transfers exist. The nerve to FDS or supinator nerves may be transferred to the AIN (MacKinnon, 2011; Hsiao, 2009).

Conclusion

1. Understanding AINS: You've gained a comprehensive overview of Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome (AINS), its definition, and its symptoms.

2. Anatomical Insights: You've learned about the anatomy of the anterior interosseous nerve, including its origins, path, and the muscles it innervates.

3. Pathophysiology: You understand the theories behind the causes of AINS, including immune neuropathy and mechanical compression, and how they contribute to the condition.

4. Clinical Presentation: You've learned how AINS presents clinically, primarily affecting motor functions without sensory loss, impacting the ability to perform specific hand movements.

5. Diagnostic Processes: You are now familiar with the diagnostic methods for AINS and various conditions that mimic AINS symptoms, helping in distinguishing AINS from other similar neuropathies.

6. Management Strategies: You've understood both conservative and surgical management options for AINS, and the indications for each approach.

7. Complications and Interventions: You've learned about the complications associated with persistent AINS and advanced surgical interventions such as nerve and tendon transfers.

Further Reading

- Aljawder A, Faqi MK, Mohamed A, Alkhalifa F. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome diagnosis and intraoperative findings: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;21:44-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.02.021. Epub 2016 Feb 20. PMID: 26921536; PMCID: PMC4802332.

- Akhondi H, Varacallo M. Anterior Interosseous Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525956/ accessed on 24th May 2024

- Vincelet Y, Journeau P, Popkov D, Haumont T, Lascombes P. The anatomical basis for anterior interosseous nerve palsy secondary to supracondylar humerus fractures in children. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013 Sep;99(5):543-7. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.04.002. Epub 2013 Aug 2. PMID: 23916783.

- Degreef I, De Smet L. Anterior interosseous nerve paralysis due to Gantzer's muscle. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004 Oct;70(5):482-4. PMID: 15587039.

- Dunn AJ, Salonen DC, Anastakis DJ. MR imaging findings of anterior interosseous nerve lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2007 Dec;36(12):1155-62. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0382-7. Epub 2007 Oct 16. PMID: 17938918.

- Sood MK, Burke FD. Anterior interosseous nerve palsy. A review of 16 cases. J Hand Surg Br. 1997 Feb;22(1):64-8. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(97)80020-4. PMID: 9061529.

- Li N, Russo K, Rando L, Gulotta-Parrish L, Sherman W, Kaye AD. Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2022 Oct 7;14(4):38678. doi: 10.52965/001c.38678. PMID: 36225171; PMCID: PMC9547755.

- Krishnan KR, Sneag DB, Feinberg JH, Wolfe SW. Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome Reconsidered: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2020 Sep;8(9):e2000011. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.20.00011. PMID: 32890049.

- Boeckstyns M. My current views on the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2022 May;47(5):542-543. doi: 10.1177/17531934221076268. Epub 2022 Feb 6. PMID: 35128983.

- Joist A, Joosten U, Wetterkamp D, Neuber M, Probst A, Rieger H. Anterior interosseous nerve compression after supracondylar fracture of the humerus: a metaanalysis. J Neurosurg. 1999 Jun;90(6):1053-6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.6.1053. PMID: 10350251.

- Chin, Douglas HCL, and Roy A. Meals. "Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome." Journal of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand 1.4 (2001): 249-257.

- Casey PJ, Moed BR. Fractures of the forearm complicated by palsy of the anterior interosseous nerve caused by a constrictive dressing. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997 Jan;79(1):122-4. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199701000-00014. PMID: 9010194.

- Ikumi A, Yoshii Y, Nagashima K, Takeuchi Y, Tatsumura M, Mammoto T, Hirano A, Yamazaki M. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome following infection with COVID-19: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023 Jun 11;17(1):253. doi: 10.1186/s13256-023-03952-8. PMID: 37301873; PMCID: PMC10257534

- Park JE, Sneag DB, Choi YS, Oh SH, Choi S. Fascicular Involvement of the Median Nerve Trunk in the Upper Arm: Manifestation as Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome With Unique Imaging Features. Korean J Radiol. 2024 May;25(5):449-458. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2023.1218. PMID: 38685735; PMCID: PMC11058432.

- Hsiao EC, Fox IK, Tung TH, Mackinnon SE. Motor nerve transfers to restore extrinsic median nerve function: case report. Hand (N Y). 2009 Mar;4(1):92-7. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9128-9. Epub 2008 Sep 19. PMID: 18807095; PMCID: PMC2654949.

- MacKinnon SE, Yee A. Flexor digitorum superficialis to anterior interosseous nerve transfer. Online video. https://surgicaleducation.wustl.edu/flexor-digitorum-superficialis-anterior-interosseous-nerve-transfer/ Accessed 26th May 2024.

- Hill NA, Howard FM, Huffer BR. The incomplete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1985 Jan;10(1):4-16. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(85)80240-9. PMID: 3968404.

- Unadkat J, Wollstein R. Anti-retroviral drug induced partial anterior interosseous nerve palsy: a case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009 Nov;62(11):e540-1. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.06.055. Epub 2008 Oct 19. PMID: 18938121.